This copy of the Royal Commission’s 1925 report started life as a loose collection of pages: Newport public library bought and bound a set to make it available for future readers in the reference library.

This copy of the Royal Commission’s 1925 report started life as a loose collection of pages: Newport public library bought and bound a set to make it available for future readers in the reference library.

A preamble to Appendix four, written by a senior MAF official in the 1920s, confirms that both retailers and shoppers alike lacked any recourse to protection from fraudulent traders and wholesalers. The document was drafted as a government response to the recommendations of the Linlithgow committee. The ministry takes every opportunity to declare that it is powerless to tackle commercial abuses such as underpaying market gardeners for their fresh produce. The Linlithgow findings are filled with talk of malpractices on a huge scale, but somehow MAF argues that this cannot be tackled head-on because very few cases would be brought. It sounds and reads like the food industry debate to set up the Grocery code 20 years ago. Click the image below, left, to download a legible PDF.

While we are on the topic, I will add some posts about French parliamentarians Jean-Paul Charié and Michel Raison, in the context of an investigation carried out for the French parliament in the 1990s

We share a planet with millions of creatures who contribute to planetary processes that keep us alive and yet in ignorance. As a species we have been technically outstanding, but we have ridden roughshod over our neighbours. While proto-agriculturists dedicated millennia to domesticating the forerunners of modern farm animals, they never stopped to reflect on the special role they played in humanity’s most positive phase.

As human populations settled, the first quality they lost was a deep awareness of a wider world beyond their existence. By leaving the land and settling in cities, humanity extinguished any remaining spark of interest in the outside world. This is just one of our nemeses emerging from the shadows. Others will catch us out sooner, but they lack the central importance of a planetary view of the natural world. Writing in Against the Grain, James C Scott reminds us that without the millennia during which prehistoric populations domesticated crops and livestock there would never have been agrarian city states. He also argues that such an important process need not be a linear progression, but that during those years human populations would have probably have lived by more than one activity, the exact combination of which would have changed with the prevailing conditions. Life in prehistory was difficult enough, without trying to stick to a linear progression from nomad to city dweller.

As human populations settled, the first quality they lost was a deep awareness of a wider world beyond their existence. By leaving the land and settling in cities, humanity extinguished any remaining spark of interest in the outside world. This is just one of our nemeses emerging from the shadows. Others will catch us out sooner, but they lack the central importance of a planetary view of the natural world. Writing in Against the Grain, James C Scott reminds us that without the millennia during which prehistoric populations domesticated crops and livestock there would never have been agrarian city states. He also argues that such an important process need not be a linear progression, but that during those years human populations would have probably have lived by more than one activity, the exact combination of which would have changed with the prevailing conditions. Life in prehistory was difficult enough, without trying to stick to a linear progression from nomad to city dweller.

Humanity is too busy chipping away at nature’s remaining toeholds to spot that we, too, depend on similarly fragile foundations. Urban Food Chains started as a repository for interesting insights into the origins of what we eat. Today, it draws from a broader set of sources, in greater depth.

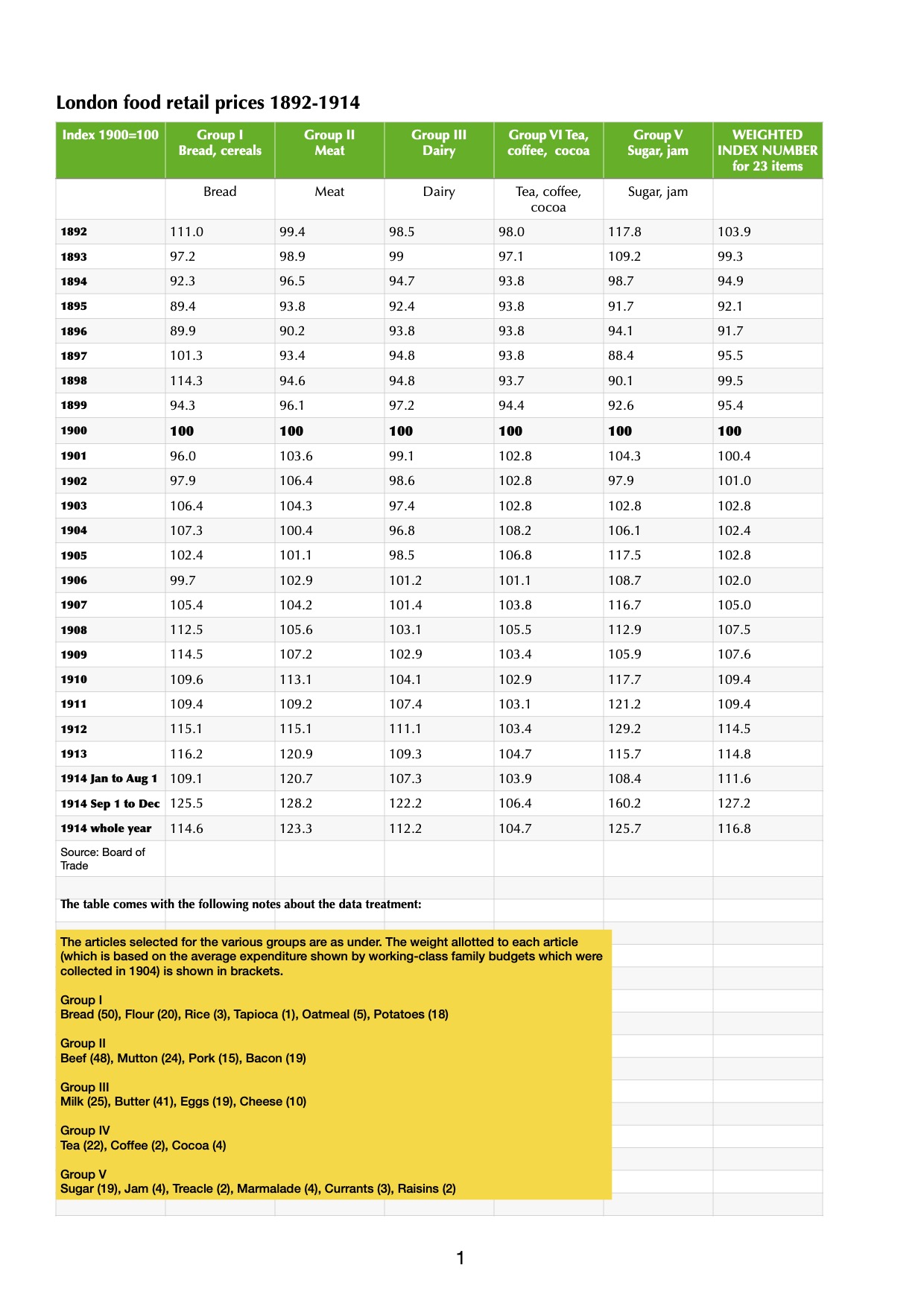

Part of the challenge of tracking down significant trends and developments in old datasets is to work out how the original compilers would have used the results. Fortunately, the Board of Trade left some clues in this snapshot of long term food price trends. The index weighting listed at the foot of the page suggests a way of reverse-engineering price differentials in a fairly robust way.

Having copied the data and the weighting factor into a two column spreadsheet listing, we can apply a SUM function to the weighting factor column. We find that there are a total of 360 tweaks applied to the base sample.

Table 6 of Appendix 3 in the Royal Commission’s report shows a series of index numbers (1900=100) for retail prices of food in London covering the years 1892 to 1914. Note that 1914 records values for January to August 1; September 1 to December and whole year. The year will be evaluated separately, since there is more movement in the economy.

Taking the figures up to 1913, bread prices rise due to currency movements (an import dependency) as well as variable levels of market availability. Meat prices, too, show a series of significant increases. The basic {index year = 1900} presentation conceals a lot of underlying trends. The difference is plain for all to see when the index weighting factors are applied from the footnote to the data. The result is a much lumpier dataset when the modified index numbers are applied (yellow box, above).

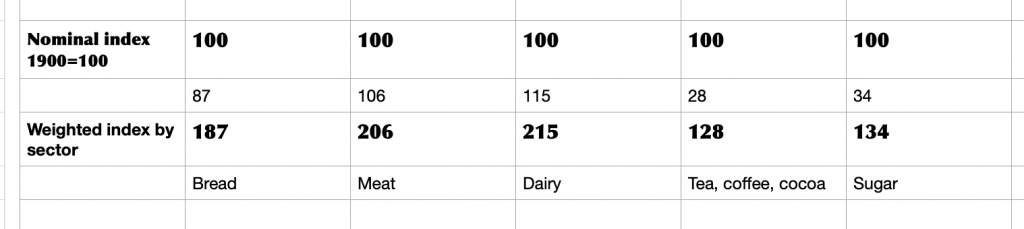

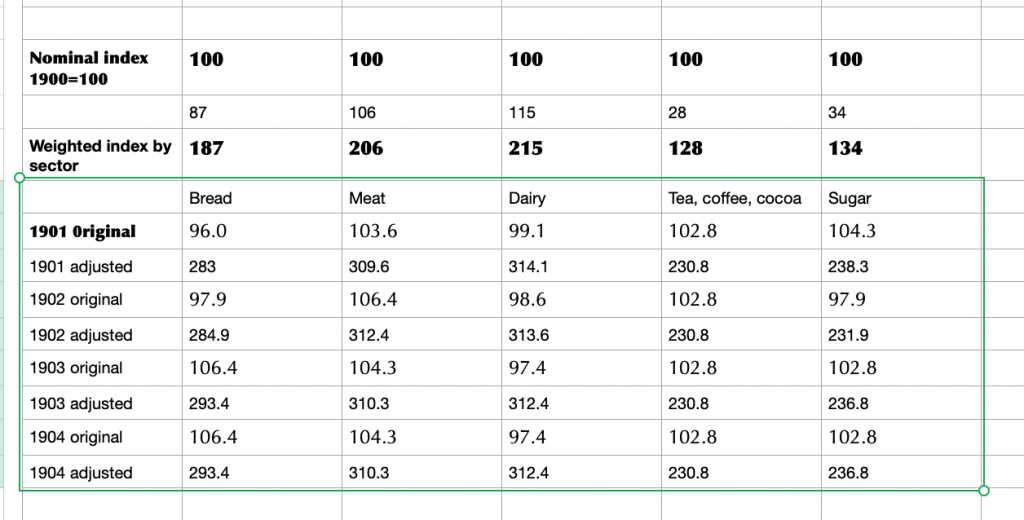

In a spreadsheet, the year looks like this:

Applied to a small sample, it starts to look like this:

At this point, it would be tempting to go in search of grocery prices, but in a period of sustained change there are easier data to gather. Take bread at the turn of the twentieth century: adding the category index adjustment to the headline figure means a total weighting of 187 for a basic product. The cornerstone of a working class diet, no less. Meat and dairy are more costly, but consumed by a more affluent group of people. Sugar, on the other hand, has modest weighting but is a sought-after category, trading strongly to every sector in the food industry: manufacturers, wholesalers, innkeepers, caterers and retailers, not to mention arcane outlets that history was about to consign to learned footnotes. We are on the lookout for qualitative data that can tell a story rather than a dusting of quantitative data that turns us into Oliver Twist, asking for more.

UK food production is set to decline in the medium term, due to a number of factors.

The first is that farmland is going out of production and is being sold off to non-farmers. The National Farmers’ Union (NFU) is in a separate running battle over government plans to impose inheritance tax on farms, neither side conceding any ground in a fiercely argued war of words. Over the past year, 400,000 hectares of farmland has been taken out of production and will never be recoverable as farmland. Prime minister Keir Starmer concedes that inheritance tax can have a significant impact, but argues that tax efficient strategies will keep farms in business. “That’s why I am absolutely confident the vast majority of farms and farmers will not be affected by this,” he told journalists. “It’s important for us to keep communicating how that works. Over the £3m, it’s then 20% rather than the usual rate (40%) and it’s payable over 10 years.” However, these figures only apply to farms passing from one generation to the next, which is no longer a reliable assumption to make. What is more, given the high average age of UK farmers, there will be less chance of the gaps between generations being as long as 10 years.

With coffee trading at over USD 4 / lb and cocoa prices hovering around GBP 9,000 / ton, traders are preparing for an increasingly stormy market. Over the past year, supply chain experts have logged a growing number of unseasonally hot weather episodes that have been followed by recent sharp rises in commodity prices. Coffee, in particular, is vulnerable to extreme conditions: the first coffee trees were found fruiting in the mid-height levels of a rain forest canopy and their modern descendants have not adapted well to growing conditions on open ground.

There are product prices that are monitored closely by retailers, which earn high margins, such as orange juice, butter or beef. The theory is that while customers are still buying products in these categories, consumer demand is intact. More problematic is the availability of a raw material like sunflower oil, a major crop in Ukraine and Bulgaria. With Ukrainian crops hit by war as well as drought last year, a wide range of food manufacturing businesses have seen sunflower oil price rises of 50% and more. It does not take many ingredient prices to start moving upwards for life to become very hard for any business that supplies multiple retailers, who systematically refuse to countenance price increases.

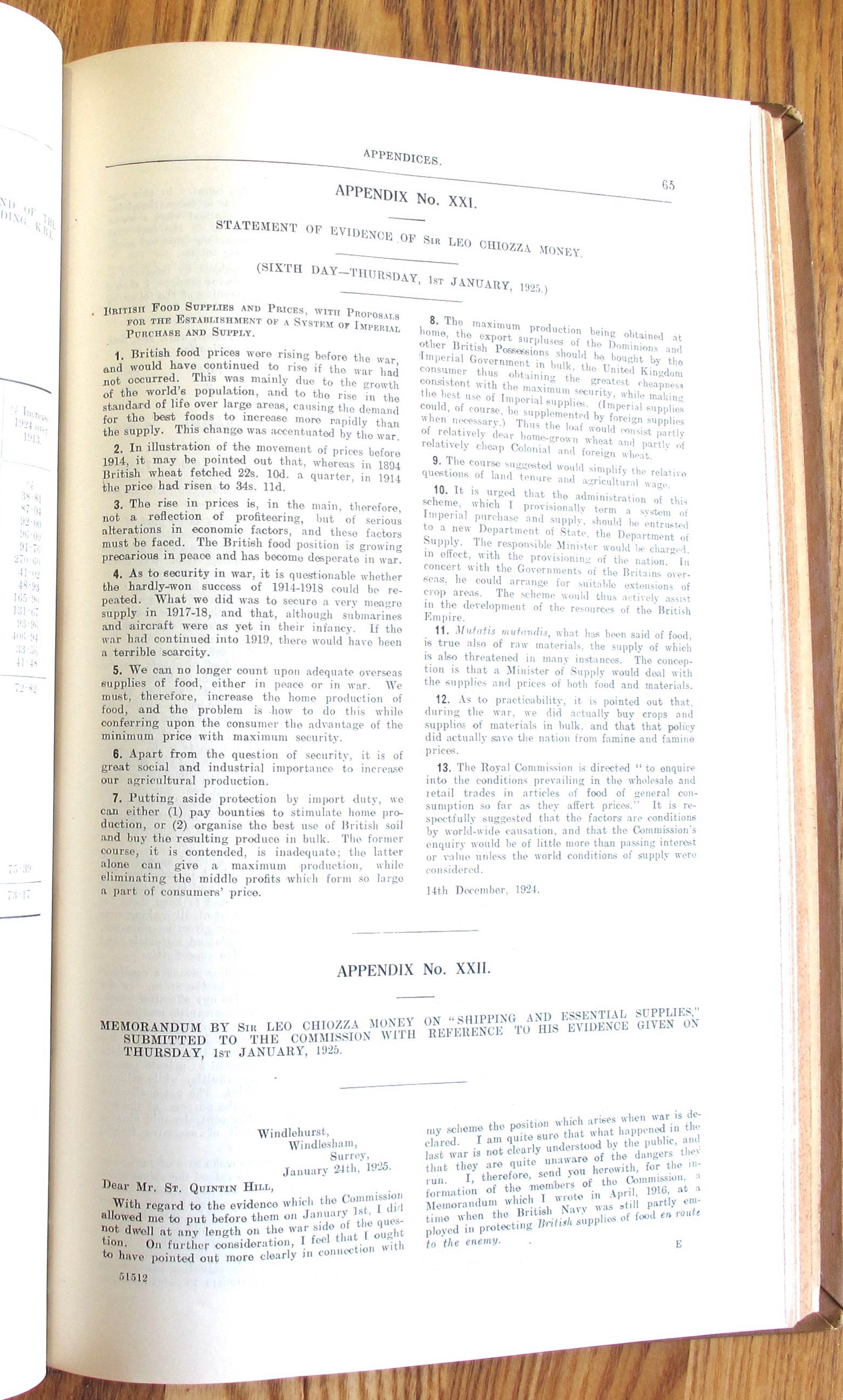

The Royal Commission on Food Prices opened on Wednesday December 10, took evidence over four days, shut down over Christmas, reconvening on New Year’s Eve and worked on New Year’s Day. At this stage in the proceedings, it is worth emphasising that prices will be quoted at face value and that the historical value of the pound was constantly changing throughout these years. There may be instances when particularly clear or striking examples occur, in which case they will be covered.

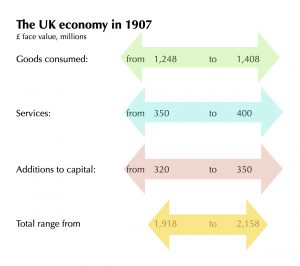

The first port of call for official figures is the Board of Trade. Working from its 1907 census of production, the prewar economy was valued at around two billion pounds (2 x 10 to the power of nine). This figure is described as “…the real income of the United Kingdom at the time to which that inquiry related.” There are a number of categories for goods consumed, each relating to the number of companies the goods went through to reach the end user: “…it was estimated that [the] charges of distribution, including the cost of transport amounted to something between one-half and two-thirds of the value of the goods at the place of production or importation.”

The aggregate value of agricultural imports (ie including some non-food products eg seeds, plants, flowers) at this time was £531,900,000, incurring £63,000,000 in customs duty and raising the customs value (in its current usage) to £595,000,000 before the goods go on to end users.

Sir Leo Chiozza Money was born in Italy in 1870 to an Anglo-Italian father and an English mother. The family moved to England in the 1890s. He worked as a journalist, wrote books on economics and earned a reputation for incisive statistical analysis. He worked for Lloyd George as a parliamentary secretary, before becoming a junior minister towards the end of the war. Born Leone Giorgio Chiozza, he added “Money” to his name, making it less foreign for English speakers to pronounce. For those among you who think “Sir Money” is a wind-up, visit this Wikipedia page.

The years around the turn of the 20th century were filled with books and other publications. Titles included British Trade and the Zollverein Issue (1902); Elements of the Fiscal Problem (1903); Riches and Poverty (1905). Money was an unswerving advocate free trade, arguing that imperial powers could not afford to give tariff preferences to the colonies, because the colonies would not be able “…to supply them (the imperialists) in sufficient quantities to support our industries and people.” It makes you wonder how poor countries survived before their resources were discovered and exploited by rich invaders.

Money’s evidence to the commission started (para 1) by identifying a growing world population and higher standards of living as a cause of rising prices. War has a very powerful impact on inflation in its own right, not least due to its disruption to transport and commercial activity in general. Money cites the historic rise of British wheat prices, (para 2) from 22 shillings a quarter in 1894 to 34 shillings a quarter in 1914. This inflation is judged to be serious rather than “profiteering” (para 3) and Money describes the situation as “precarious in peace and desperate in war.”

The UK was lucky to get through the first world war, when its supply chains came under fire (para 4) from submarines and other vessels that were being developed. Britain could not and should not expect to feed itself on imported food at peace or at war (para 5). This is a valid point, coming as it does with a call to renew the country’s agricultural system. More than just a good thing, (para 6) it is “… of great social and industrial importance.” He develops this theme (para 7) and argues that scaling up agricultural production will remove middlemen from supply chains and lead to cheaper retail prices. Nice try, but wide of the mark. Likewise, his proposition that surpluses from British dominions and possessions (para 8) should be bought up for sale in the UK begs a number of questions, such as who decides what is surplus or not. The notion that a loaf might be made up of “partly of relatively dear home-grown wheat and relatively cheap Colonial and foreign wheat…” is fanciful at best. As is the suggestion that Money’s plan would resolve issues around land tenure and the agricultural wage (para 9).

Money proposes a ministry to manage the price components for the nation’s food supply (para 10). While the government did indeed establish a food ministry as Europe slipped back into war, its purpose was to ensure there was food to eat rather than numbers to crunch. Like many other economists, Money is quick to point out that what applies in one sector of the economy can probably be re-used and applied elsewhere (para 12). It is also an efficient way of spreading any policy shortcomings from one sector to another.

A cornerstone of Urban Food Chains crystallised this evening. Fundamental to the structure of a supply chain is the basic unit of transport and energy. Taking three major themes of this blog, let’s unpack the topic. First, before the dawn of time, generations of early agriculturists worked for millennia to domesticate species and crops that we would recognise today. They also tamed fire, an evolutionary trump card. Their lasting achievement was to breed forerunners of today’s strategic ungulates: cows, pigs, sheep and horses. Fast forward to the early twentieth century, when the first world war slaughtered millions of draft animals.

This high tech cull of horses, in particular, damaged the bedrock of the agricultural world. Livestock numbers would take decades to restore, if indeed there was either the economic resources or the political will to do so. The first world war was a reset that made way for change on a global scale, for humans and animals alike. Thousands of years spent establishing stable working relationships turned to dust in the heat of battle.

The penny dropped when I read Christopher Turnor, an author of the time, complaining that the UK had too many pastures, they were blocking food production. The origins of all this empty grassland are to be found in Edwardian England, but the wartime cull of draft animals accelerated the trend. The rest is not so much history as a race to plug the economic gaps left by the ravages of war.

To paraphrase Saint John, in the beginning was the meal. And the meal was with God…

We live in a world with more explanations than questions, more doubts than answers, more belief than knowledge. What sustains us is an unseen chain of events that conspire to make human life happen, whatever it takes. Our dependence on this process is total. Welcome to the world of food.

Our shared origins go back to the beginning of time before crops or livestock had been domesticated. There is general agreement once hominids had domesticated fire — tamed is probably a better word — there was a further four to six millennia before domesticated animals and crops emerged on the scene. Scholars may disagree over when this change came about, but we can be sure that until it was a fait accompli, everything else in the story of civilisation was on hold. There are quibbles about when exactly such a change can taken as read, but everybody is counting in millennia.

The rest is history. The trouble with history is its dependence on written records and sometimes incorrect attribution of artefacts. The reason we know so little about early agrarian populations is because they had neither written records nor surviving artefacts to bear witness to their passing. This is a pity, since what we do know about these groups is that they lived in harmony with nature and were environmentally enlightened. We are indebted to some of the world’s most dedicated and skillful archaeologists, who have traced the remains of villages that were built in the trackless alluvial wetlands. At this time, hominids and animals fed future generations of flora and fauna. Man was still bound to the laws of nature at this time.

When the world’s first states emerged, they were expressions of an agrarian social structure. Their dealings with the world around them were probably more extensive than we will ever know. What matters is that we learn and understand from such scraps as we can glean, to focus on value without being diverted by units of account.