Since starting this blog a few years ago, I have developed an ever stronger view that urban centres depend completely on food coming from the rural hinterland and further afield. Sustainable supply chains are a vital part of our survival. Of all the capital cities in the world, only Havana can claim to have made real structural changes to its food production, becoming self sufficient out of necessity in just a few years. This was the result of the end of Cuba’s role as a client state for the Soviet bloc, rather than any conscious policy decision. It is a sea change that Cuban citizens have adapted to with aplomb, re-organising their food supply chain to meet the changed circumstances. It is also a warning to UK consumers, since we have no national plan B for any of our food supplies.

The space in which food, money and power interact deserves more of our attention than we want to give it. Our lives depend on it and yet we take so much for granted. We started the 21st century assuming that retailers’ shelves would always be filled with tempting things to eat, whatever the season, whatever is happening in the world around us. We will understand differently very soon.

Urban Food Chains sets out to dust off and revisit the origins of what we somehow assumed to be normal until quite recently. Some of the material on this site started life in previous attempts to generate a spark of interest in the most far-reaching but under-reported aspects of modern life.

The idea that the natural world is somehow a separate space from the industrial world is a dangerous illusion. Every shred of toxic waste, every tonne of exhaust gases to have risen up urban chimmneys, every tank of diesel persists in some form, however remotely from its origins, lingering in the biosphere. Diluted and dispersed, but still present, pollution has been with us for millennia.

When humanity started to make barrels for shipping food and drink, these needed a simple management system. Every barrel has a filling hole, known as an eye (French: oeil): it earns the name because you have to put your eye to the hole to see if there is any space left. England adopted the old Norman French term oeuillage, which later became the English word ullage, referring to the space left in the barrel. More recently, looking for a term that captures the combination of economic claustrophobia and the lack of space available for the necessary processes in food production, I coined the term zero-ullage, since world we inhabit is not just full, it is choking off the economy and production in a frenzied attempt to ignore the truth.

***

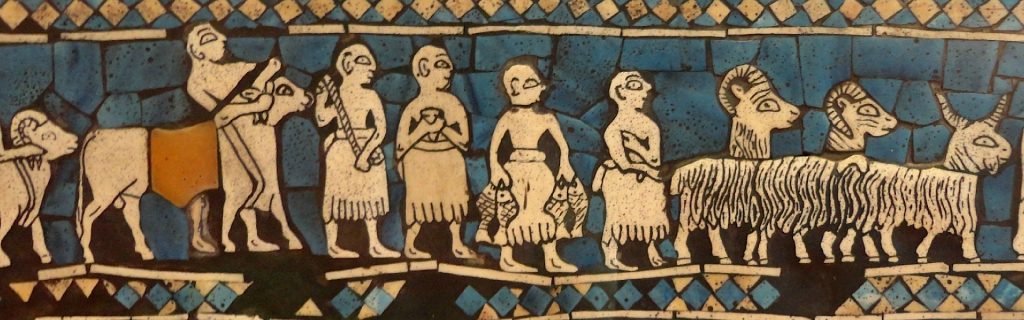

In his book Against the Grain, James Scott makes a case for supposing that the prehistoric agrarian states in what later became Sumeria and the Tigris basin chose to build their economies on grain.

Perversely, this was not because a grain-based diet suited human populations, but because it was simpler to organise a tax on grain harvests than other forms of agriculture. As early as 4000 BCE, administrative inertia saw human endeavours harnessed to socio-political convenience rather than taking a broader view of what a sustainable diet might look like.

As one might expect, over time the early civilisations foundered and expired as they became unsustainable for reasons we can only guess at. The adverse environmental impact of continuous grain crops was not given widespread credence until after the plains of north America had been turned into rolling cereal monocultures. Even then, the presence of crop treatment residues was not measured in the environment until the late twentieth century.

At the dawn of pre-history, millennia passed during which ungulates and homo sapiens grew accustomed to each other in a process of domestication. To be sustainable, domestication needs to be a two-way street. Just over one century ago, the inertia of industrial growth and its technological development started to push horses aside in a one-sided power grab. Millions of draft animals were culled on battlefields from South Africa to Flanders, during a century that spanned the second Boer war to the first world war and beyond. Carving a new role for the automotive industries of the day ensured the future ascendency of future generations of technocrats and engineers, without any restraint or duty of care for the animal world. The consequences of hubris on this scale are only now starting to be recognised before it is too late.

In other words, humanity needs to respect the needs of the wildlife we share a home with. Nature is not an endless resource for human exploitation. We need to moderate our expectations.

Somewhere between what we think of as the cradle of civilisation and the modern age, humanity has lost the plot and fallen victim to hubris. Now called Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, to cite but three countries where prehistory runs deep, there arose agrarian civilisations that assumed power over their citizens. These agricultural systems later failed, centuries later.

They did not disappear without trace, but managed to make a basic error that we are repeating with our infinitely more powerful technology and greater knowledge. Treating the undomesticated world as a blank canvas for human enterprise, endeavours or whim, in that order, is not going to work. Whether humanity could ever have managed things better is a moot point, but hubris is raising its ugly head over the exponential rates of exploitation that identify industrial society.

It is necessary to start by defining a food chain and establishing the difference between a food chain and a supply chain. The former feeds successive links within its hierarchy, the latter is an artifice for moving goods all over the Earth, using the available technologies of the day.

The links in an urban food chain have been subjected to millennia of domestication, which has transformed the cut and thrust of an “eat or be eaten” state of nature into a collection of convenient and manageable food products which have undergone one or more processes, such as slaughter, harvest or cooking. This goes a long way towards illuminating the nature of the supply chain and explaining the distinction I made earlier. A supply chain is an artificial administrative conduit through which goods are transported, some of which may be food.

It does not preclude catching or finding food in nature, but this occurs independently of the supply chain, even if the supply chain has a dedicated node to integrate naturally occurring resources. An example of such a node could be a fish cannery, which might be seasonal (eg salmon canneries in north America) or work all the year round (eg tuna canneries in the Indian Ocean).

Urban populations cannot live without functioning supply chains and their future depends on being able to adapt existing capabilities to meet changing circumstances. The length and complexity of a supply chain increases its risk of failure: seemingly sustainable civilisations in prehistory have crumbled to dust for reasons we can only guess at.

If we are to avoid becoming collateral damage in a supply chain failure, we need to review the foundations of those supply chains. Can we can adapt to foreseeable changes in the medium term? We may still become collateral damage, but we will at least have queried the assumptions that we once made without thinking. In no particular order, here are some of them now.

Climate

There is enough evidence for any right-thinking adult to suppose that climate change is not just happening, but moving faster than our leaders are prepared to admit. We need to expect seasons with no predictable patterns to them, even if we cannot meet the challenges such changes bring head on.

Political and commercial climate

The longer a supply chain is, the more vulnerable it will be to disruption along its length. The complexity of a supply chain increases with the number of people it serves and the number of nodes it contains. The additional complexities arising from Brexit are inevitable, since the additional set of customs clearance requirements are effectively an extra node that did not exist previously.

Customs requirements

The UK has barely started to adapt to being a third country in the grip of post-Brexit chaos. Conveniently for some, this has taken a back seat to the pandemic. After decades as a member of the EU, there should be no surprises as to what third country status requires of the UK. The sight of government ministers feigning surprise at some of the border inspection requirements to ship goods to the EU is a sign of incompetence.

Technology

Supply chains are structured and literally built on the technology of the day. Thus, in the late 1860s, the railway network determined the routes by which home-produced foods such as eggs or milk travelled to market. The railway network around Yorkshire cities such as Wakefield established the county’s rhubarb triangle, Steam ships provided a similar capacity for carrying imports and inshore freight between coastal centres. A century later, the rail network was cut back and more goods travelled by road. In simple terms, road freight handling technology had become more sophisticated and businesses such as abattoirs and creameries, that once depended on access to the railway, no longer need the dedicated railway access.

Domestication

It would be hard to argue that humanity is the only species to process and store food. Bees make honey for their colonies; countless species are either a source of food in their own right or store food for later consumption during times of plenty; migration and other mass events are feeding opportunities for predators. The difference is that the survival of humanity depends on a body of processes and phenomena, some of which are anything but natural. The vulnerability is not necessarily inherent in the production or processes used, but the anthropocentric assumption that these are either normal or natural.

Leave a Reply