Live horse power

Horses and other equidae occupy a very special place in human hearts, even if the relationship changes in the way it is expressed from one place to the next. The value of horses in history has always been high: they are a sign of a rich household or a working relationship. It is easy to forget that a horse rarely works alone and that every working pair or team must be matched in size and weight. There is a wide range of animals that will be drafted in, but the final choice will be based on the work ahead. A light horse will pull a small cart on smooth terrain, but not steep gradients, nor heavily laden.

Agricultural stock will often be one of the four main heavy horse breeds: a compact Suffolk Punch; a tall Airedale; a stocky French Percheron or an imposing Shire horse, with a heavy bone structure and sturdy muscles. The Suffolk Punch was bred to work light Suffolk soils and will struggle in heavy conditions; the Airedale has a distinctive way of maximising leverage with its high shoulders; the Percheron is very muscular but does not stand as tall nor as broad as a Shire. From a very cursory look at the characteristics of just four breeds it very quickly becomes clear that mix and match is not an option.

To add to the suspense, every working horse down to the roughest hack will have a collection of harness and accessories to meet their needs. This will need to travel with the animal wherever it goes. It should come as no surprise then, to learn that transporting a horse on the railway cost an arm and a leg in the early 20th century. But this was nothing compared to the eye-watering cost of procuring hundreds of immediately useable, ie trained horses from around the world.

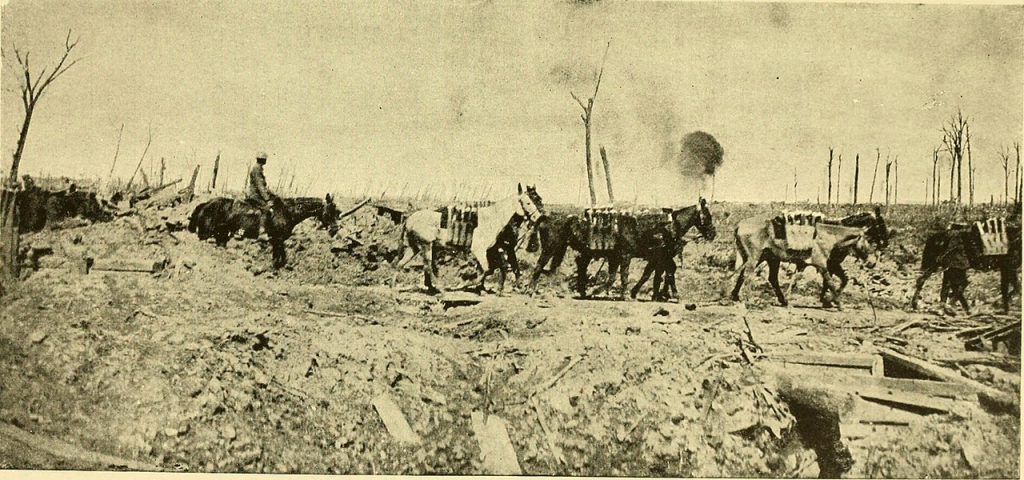

The first world war saw equine fatalities of nearly half a million animals on the British side alone, with a total of eight million draft animals lost in all the theatres of war. Poor weather conditions, with heavy rain and snow, combined with a British insistence on clipping horses fur to slow down the spread of mange and lice among British soldiers, accounted for about 80% of the British losses. Horses were routinely turned out to spend the night in fields of deep mud with no hay or grass to eat. At the end of the hostilities, only horses belonging to British officers, 65,000 in all, were shipped back to the UK. Of the rest, 85,000 older animals were sold to French and Belgian butchers to feed the local population; half a million were sold to French farmers to rebuild their holdings and a further 100,000 held in the UK were sold off as military surplus. Soldiers who had built close relationships to their equine companions were bereft of their company at a stroke. But it was the butchering of horses for food that upset a great number of troops, many of them having spent months risking their own lives, let alone the lives of their animals. In terms of domestication, the bonds they shared were as strong as family ties.

For more articles about horses in a human mindset, here is a list of them.

The Verdun post, pretty grim: https://urbanfoodchains.uk/2025/04/21/verdun-the-turning-point/