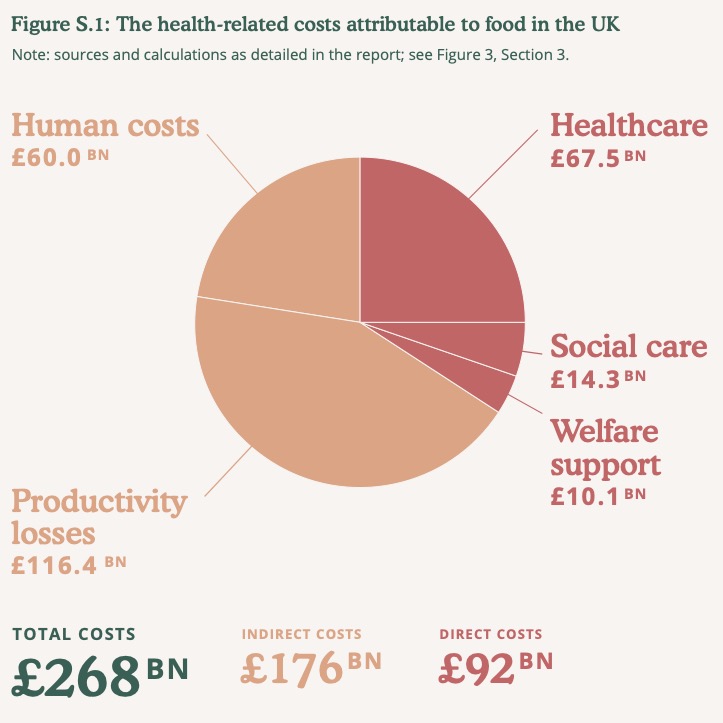

The UK government spends more than GBP 90 billion a year treating chronic food-related illness, according to the Food, Farming & Countryside Commission (FFCC). Researchers estimate that investing half that sum would be enough to make a healthy diet accessible to everyone living in the British Isles. The full extent of the damage caused to the UK economy by a dysfunctional food sector is GBP 268 billion pounds a year, taking lost productivity and early mortality into account, FFCC warns.

The Food, Farming & Countryside Commission is an independent charity, set up in 2017 to inform and extend public involvement in ongoing discussions about food and farming. Using government data as a starting point, FFCC argues that it would be significantly cheaper to produce healthy food in the first place. More to the point, it is not an option to go on footing the bill for damaged public health resulting from the commercial sector’s activities. There is simply not enough money in the kitty and time is running out.

Researchers took into account government estimates of productivity and lost earnings arising from chronic illnesses. These indirect costs are borne by a range of actors in the economy, such as local government departments. Such costs are real expenditure, but the total figure is not recorded as a single aggregate figure. When combined with the initial figures, the result is a more imposing figure and looks like figure S1.

The direct costs (in red) are existing government data; indirect costs (in orange) indicate the economic impact associated with the prevailing levels of unemployment and early mortality. Like the submerged part of an iceberg, we ignore these costs at our peril.

Working with indirect costs opens the door to accusations of misinterpretation, but economists have worked hard to establish methods that can avoid serious pratfalls. Healthcare is supported by a wide range of funding sources, from government down to private individuals. The money is real enough, even when it comes from private individuals. It just becomes harder to count. There are times when budgets for nearby or related units will be skimmed to meet ad hoc requirements. Welcome to the economists’ underworld, where early retirement due to ill health is just another negative variable.