Up and down the UK, we see Big Issue vendors on the high streets of Britain, clutching a bundles of magazines in a bid to sell an incisive vision of consumer society. As an example of the high standards of news writing that fills the pages of the magazine, issue 1060 published at the end of January carries a well-researched snapshot of the decline that is tightening its grip on British high streets and shopping centres. A downpage panel records the 2.2% year on year drop in footfall, as fewer shoppers venture out in 2024. Some 13,500 shops closed during the year, nearly one third more than the previous year’s 10,494 retail closures. This averages 37 shops closing every day, according to the Centre for Retail Research. Figures from the Altus Group record that there are now 38,989 pubs still trading in the UK, after 400 closed in 2024. Some of this decline could be laid at the feet of online shoppers, but the figures tell a story of dwindling economic activity.

What can £38/week buy?

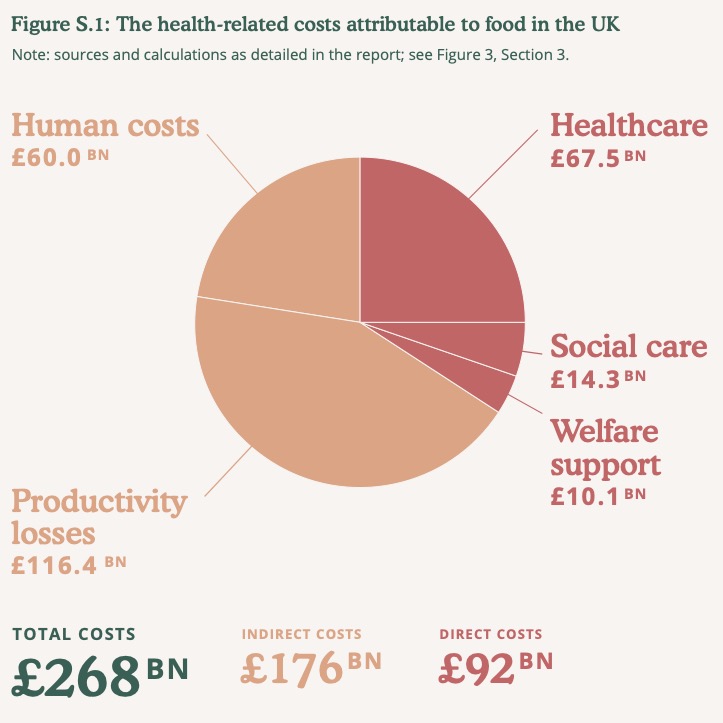

The impact of Government policy to improve the national diet comes with proportionally higher costs for poor households. This would apply to any government, of any stripe and any motivation. Structural change in food policy throws differences in earnings into sharp relief. When the Food Standards Agency published the Eatwell Guide in 2016, a headline price rise of £38 a week would mean a doubling in food bills for poor households, compared to increases of just over a third for affluent consumers. Using Eatwell data on a national scale, the Food, Farming and Countryside Commission (FFCC) researchers calculate that legislating for a healthy, sustainable national diet would come with a £57 billion price tag. This is not unreasonable, indeed it is good value, given that the direct cost of healthcare arising from diet-related illness is running at £91 billion, lost productivity is costing the economy an estimated £116 billion a year and the human cost a further 60 billion a year. The numbers basically accuse the food industry of being more interested in making money than feeding people. However, the scale and scope of the money extracted from UK health authorities by pharmaceutical corporations is several orders of magnitude greater and no less reprehensible.

If the market economy functions as one might have hoped, would this ever have occurred in the first place? Part of the problem with economics is that its practitioners quite cheerfully play “what if?” games as they go along. The problem is not that a variable might be unreliable, but that the outcome can change in so many ways that it is impossible to attribute a given outcome with a single input. Treating the food/health sectors as a series of events, for example, creates a dislocated view of the biosphere, with more gaps than development. Some gaps are inevitable, but you can have too much of a good thing.

Big Food’s Big Secret

The UK government spends more than GBP 90 billion a year treating chronic food-related illness, according to the Food, Farming & Countryside Commission (FFCC). Researchers estimate that investing half that sum would be enough to make a healthy diet accessible to everyone living in the British Isles. The full extent of the damage caused to the UK economy by a dysfunctional food sector is GBP 268 billion pounds a year, taking lost productivity and early mortality into account, FFCC warns.

The Food, Farming & Countryside Commission is an independent charity, set up in 2017 to inform and extend public involvement in ongoing discussions about food and farming. Using government data as a starting point, FFCC argues that it would be significantly cheaper to produce healthy food in the first place. More to the point, it is not an option to go on footing the bill for damaged public health resulting from the commercial sector’s activities. There is simply not enough money in the kitty and time is running out.

Researchers took into account government estimates of productivity and lost earnings arising from chronic illnesses. These indirect costs are borne by a range of actors in the economy, such as local government departments. Such costs are real expenditure, but the total figure is not recorded as a single aggregate figure. When combined with the initial figures, the result is a more imposing figure and looks like figure S1.

The direct costs (in red) are existing government data; indirect costs (in orange) indicate the economic impact associated with the prevailing levels of unemployment and early mortality. Like the submerged part of an iceberg, we ignore these costs at our peril.

Working with indirect costs opens the door to accusations of misinterpretation, but economists have worked hard to establish methods that can avoid serious pratfalls. Healthcare is supported by a wide range of funding sources, from government down to private individuals. The money is real enough, even when it comes from private individuals. It just becomes harder to count. There are times when budgets for nearby or related units will be skimmed to meet ad hoc requirements. Welcome to the economists’ underworld, where early retirement due to ill health is just another negative variable.

The real cost of doing nothing

The food industry is making more people ill with processed foods than its management would ever admit, according to the Food, Farming and Countryside Commission. Researchers put the cost of chronic illness to the UK economy at GBP 268 billion. (https://ffcc.co.uk/publications/the-false-economy-of-big-food)This figure is four times the cost of fixing the problem, the report’s authors estimate. The opening statement reads like this:

New analysis commissioned by the Food, Farming and Countryside Commission (FFCC) has found that the costs of Britain’s unhealthy food system amount to £268 billion every year – almost equivalent to the total annual UK healthcare spend.

The report by Professor Tim Jackson provides the first comprehensive estimate of the food-related cost of chronic disease, caused by the current food system. The analysis combines direct costs – the costs paid for from the public purse – including healthcare costs, social care costs and welfare, and indirect costs – costs that don’t show up in government accounts – which are productivity losses and human costs.It concludes that £268 billion is the food-related cost of chronic disease in the UK – calculated by combining healthcare (£67.5bn), social care (£14.3bn), welfare (£10.1bn), productivity (£116.4bn) and human cost (£60bn) of chronic disease attributable to the current food ecosystem.

The report makes the case for a new economy of food, anchored in three key principles:

- the right of every citizen – irrespective of class, income, gender, geography, race or age – to sufficient, affordable, healthy food;

- a regulatory environment which curtails the power of Big Food, promotes dietary health and halts the rise of chronic disease;

- a financial architecture that redirects money away from perverse subsidies and post-hoc damage limitation, towards preventive healthcare and the production of sustainable, nutritious food.

Brexit’s hostile environment

The British establishment has a number of strengths, not all of them positive. Long standing cultural patterns such as racism or mysogyny are not always associated with the toxic knee jerk emotions they unleash. Sometimes stretching back for generations, past prejudices cast veiled shadows over current mindsets.

A common marker of such underlying tendencies is the urge to promote a hostile environment for groups that the establishment does not feel comfortable around. Avoiding confrontation, but nevertheless antagonistic towards them, officialdom reserves a superficial welcome for people of colour, migrants or women, among others.

At an institutional level, something similar could be seen in the gung-ho pursuit of aggressive tactics throughout the Brexit negotiations, during which concessions were demanded with little thought of any form of quid pro quo.

Left to its own devices, the civil service is capable of creating procedures and regulations that contribute to an underlying malaise. This administrative hostile environment casts a shadow on those who are bound by or who enforce such oppressive rules. The Border Transit Operating Model offers a number of examples of the genre, such as the Common User Charge (CUC).

DEFRA consulted with business leaders last summer, promising to share its findings in the autumn. For months there was talk of a “world class” system, but no operational detail that anyone could use for the day to day running of their business.

On January 19, Walthamstow MP Stella Creasy challenged the government’s wall of silence surrounding the Common User Charge. Here is how Hansard recorded the occasion.

[She told the House that]: “The charge is intended to apply to each consignment, whether it is one leg of lamb or a van full of reindeer and frogs’ legs. As 65% of lorries coming into this country carry multiple consignments, known as groupage, it is clear how expensive this way of applying the charge will be.

“The Government have therefore chosen to fund the new border by imposing fees directly on businesses that import. The pledge that Brexit would be a bonfire of regulation turned into a smouldering pile of paperwork that will kill imports for small businesses. Can I just put it on the record on behalf of British business — this is mad.”

Parliamentary Undersecretary of State of Environment Food and Rural Affairs, Rebecca Pow, replied:

“We have provided further facilitation and guidance for importers using groupage models – the honourable Lady referred to groupage models, where a lorry delivers a whole lot of different models in one lorry – in terms of moving sanitary and phytosanitary goods into the UK, in order to make the system of certification more streamlined.”

The word “consignment” is completely absent from the minister’s frankly incoherent reply, which is a thinly-disguised attempt to buy time.

Creasy then asked the government on February 8 whether a decision had been taken as to the rate at which the Common User Charge would be fixed and when such a decision might be published. Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, Mark Spencer, replied on February 27 that an announcement would be made “imminently.” He added that: “This will help commercial ports in setting charges for their own facilities and provide traders with time to make the necessary finance, accounting and operational arrangements.” More stalling, more flannel, more empty words.

The simple fact is that by the time the final workings of the CUC were revealed to the public, there was less than a month to do anything about it. For those who are still catching up with reality, the British government is rolling out a punitive tax on imported goods, starting on April 30.

For those who are up to speed with this news, there is a very real prospect that European traders will resent the British government’s crude attempt to monetise inland inspection facilities. The result will probably be a sudden and brutal drop in food shipments to the UK.

Cumulative cereal crises (1)

Climate change can be expected to set off multiple simultaneous food crises around the world. The following post started with a story about rice, then collected a footnote about wheat from war-torn Ukraine and another from southern Europe in the grip of a drought. It could have had a snippet from north America’s struggling maize crop, but that will have to wait.

***

India is curbing its rice exports in the face of predicted shortages. The country is the world’s biggest exporter of rice, selling 22,000 tonnes abroad in the crop year 2023. An estimated 10% of the world’s rice production is exported and traded internationally, according to data curated by the All India Rice Exporters Association . The tonnages traded internationally are less than one might have expected for one of the world’s most important cereal crops: global production tops 50 million tonnes.

In all its diverse forms, rice supplies about a fifth of the human calorie intake. As a labour intensive crop with very specific irrigation needs, rice does not travel as far or as readily as other mainstream cereals like wheat or barley. Rice is a complex commodity, with many specialist varieties and qualities. Indian rice growers produce premium grades of scented basmati rice for export sales, in addition to more basic varieties. The guiding principle is that all basmati rice is scented, but not all scented rice is basmati.

The first two months of the new growing season (2023-2024) have seen growth of just over 6% in volumes traded internationally, even though India imposed an export duty of 20% on rice part way through the 2022 crop year. The additional duty has not damped down demand, which remains strong. The current season has been hit by more rain and flooding than usual. “We are still keeping our fingers crossed over the likely impact of El Nino” AIREA president Nathi Ram Gupta told his members.

Rice export figures from India and all the significant growing areas across the world for the 2022-23 crop year have not moved dramatically against previous years. But past performance is a notoriously unreliable indicator of future shortages in any sector of the world economy.

This week there are reports of Russian military action destroying a grain silo in Odessa. First reports suggest that 40,000 tonnes of wheat were destroyed in the attack: more significantly the action removes storage capacity for 120,000 tonnes of grain in the middle of the harvest. One single incident casts a shadow over both dockside facilities and the safety of shipping that up until now had been able to deliver wheat to east Africa.

With southern Europe in the grip of a persistent heat wave, there are signs of firmer prices for durum wheat, which is grown across Spain and Italy. Since July 1, prices for European durum wheat price have bottomed out from a pre-harvest low point of around 330 Euros/tonne and moved up to almost 400 by late July. Southern European shoppers are high volume consumers of pasta, which is likely to push up prices of durum wheat in the coming weeks.