Autoclave and retort are two names for pressure cooking vessels used in food manufacturing to sterilise canned food and in later versions by engineering firms to cure rubber tyres. The starting point was known as a steam digester, attributed to French scientist Denis Papin, in 1679.

The hazards of working with steam under pressure very quickly became apparent and Papin devised a safety valve to mitigate the risk of explosion, leading many to refer to it as the Papin digester. It was called a digester because it was generally used to apply heat and pressure to bones, leaving cooked bones soft and friable for bonemeal. Other processes were developed for this piece of equipment, from which Papin developed a prototype steam engine. This was subsequently developed into the static steam engines built by Thomas Newcomen.

Chevalier-Appert, a nephew of Nicolas, invented the first reliable pressure gauge for retorts and autoclaves in 1852. This was an essential accessory to prevent explosions and standardise the process. Early retorts comprised a steel vessel, with a metal basket to hold filled bottles or cans. Later versions were fitted with systems that allowed product to be rotated as it cooked, reducing the cooking time. To start a cooking cycle, the vessel is loaded and the door closed. Steam is brought into the cooking chamber and the contents cooked for the required time at the necessary temperature. Once cooked, the steam was turned off and the retort allowed to cool.

A cooking cycle can last for hours, not finishing until the centre of the load had been subjected to a predetermined temperature and for a set period of time. The result is overcooked product on the outside to be sure that the centre cooked properly. Later refinements include automated loading, a key advance to raising throughput.

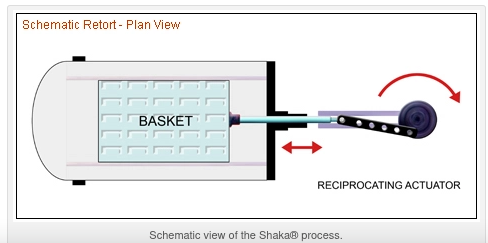

The next milestone, in the late twentieth century, was reached by Richard Walden, a process engineer working for Carnaud-Metalbox. Convinced that it was time to make retorts more efficient, he devised what is now referred to as the Shaka retort, which shakes its load backwards and forwards, driven by a reciprocating actuator at speeds of more than 100 cycles per minute.

It was clear from the outset that when the prototype reached a certain speed, the load underwent a quantum cooking effect, a “sonic boom” for food, so to speak. Depending on the consistency of the product, cooking time went down dramatically. Further details are available here: https://shakaprocess.wordpress.com/what-is-the-shaka-process/

Walden fixed the amplitude on the prototype at around 150mm and varied the speed or rpm on reciprocating arm. For any given product viscosity, Walden could identify a threshold at which a quantum heat transfer took place in the cooking vessel. Further increases in the rpm had no significant effect on cooking times.

Shaka is an undisputed milestone achievement, but has yet to persuade mainstream food manufacturers to scale down their investments in energy-hungry retort lines. The technology has been licensed to two retort manufacturers, Steriflow in France and Allpax in the USA. Prototype, pilot and production models are all available. Although the Shaka units are smaller than their conventional counterparts, they can achieve the same throughput with multiple shorter cooking cycles.