Forget the presentations, the bonding exercises, the sales pitches, executive bonuses, company cars and other corporate paraphenalia: it belongs in the past. Today we need to adjust to accelerating climate change, political instability, there simply isn’t time for the other stuff. People are waking up to the planet’s problems a couple of generations too late,

Who is driving the business?

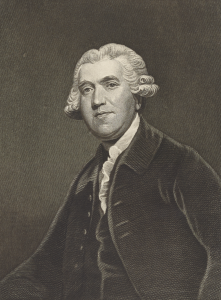

Census figures do not come close to providing any insight into the level or nature of economic activity in a given county or town. The productivity of 100 potters in Stoke on Trent during the 18th century could be considered substantial, but of a different quality to Josiah Wedgwood (in portrait). Few would argue that Wedgwood was a powerful agent of change on many fronts, yet this famous Unitarian went unrecorded in Anglican records of any kind.

Technology is a key to transforming productivity, but only in the hands of people with vision. Technical finesse will not redeem a boring or uninspired artefact, but serve to emphasise its lack of distinction.

Tony Wrigley has written this accessible account of how the treatment of census data is changing in today’s more broadly-based research world. The answers to life’s mysteries are no better than the questions we pose to define them.

What’s driving the business?

Own label instant coffees are made with the same sort of coffee beans as their branded counterparts. The only difference is that the retailers control the pricing and, as retail brand owners, they are not held to ransom for shelf money. The Consumer Association magazine Which? is advising readers to switch to cheaper own label alternatives. To stand up its story, Which? gives the example of a 200g jar of Nescafé Original, which was selling for five and a half quid in supermarkets last year and is now the thick end of eight quid a pop on Ocado. Given the scale of Nescafé’s economies of scale in the procurement and manufacturing stages, how does one explain a 30% year on year price rise? Sure, the beans are more expensive, but what does the future hold for premium home delivery shopping channels?

Time to reflect?

We share a planet with millions of creatures who contribute to planetary processes that keep us alive and yet in ignorance. As a species we have been technically outstanding, but we have ridden roughshod over our neighbours. While proto-agriculturists dedicated millennia to domesticating the forerunners of modern farm animals, they never stopped to reflect on the special role they played in humanity’s most positive phase.

As human populations settled, the first quality they lost was a deep awareness of a wider world beyond their existence. By leaving the land and settling in cities, humanity extinguished any remaining spark of interest in the outside world. This is just one of our nemeses emerging from the shadows. Others will catch us out sooner, but they lack the central importance of a planetary view of the natural world. Writing in Against the Grain, James C Scott reminds us that without the millennia during which prehistoric populations domesticated crops and livestock there would never have been agrarian city states. He also argues that such an important process need not be a linear progression, but that during those years human populations would have probably have lived by more than one activity, the exact combination of which would have changed with the prevailing conditions. Life in prehistory was difficult enough, without trying to stick to a linear progression from nomad to city dweller.

Humanity is too busy chipping away at nature’s remaining toeholds to spot that we, too, depend on similarly fragile foundations. Urban Food Chains started as a repository for interesting insights into the origins of what we eat. Today, it draws from a broader set of sources, in greater depth.

Process of elimination

If there is so much money at stake, how strong is the case for accusing food manufacturers of Ultra Processed Foods (UPFs) of wilful distortion? The arrival of wall to wall processed foods in British aisles in postwar years has been accompanied by rising numbers of patients needing treatment for heart disease and diabetes. While the nation gorges on sugar, salt and saturated fats, there is a drop in foods that bring whole grains, let alone fruit and vegetables. Processing very finely divided ingredients allows fertilisers and other toxic residues to spread downstream through the food chain. More worrying is the uptake of UFPs in the population. These foods now account for 57% of the adult diet and 66% of adolescent food intake. The health issues in later life are already filling up British hospitals and soak up two thirds of the health budget.

Global factors keep pushing up UK food prices

Over the past two years, climate change and rising energy costs have been the two biggest sources of food price rises. Analysis by The Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit (ECIU) suggests that even if energy costs ease, climate change will carry on pushing up food prices in years to come. With hundreds of acres of UK farmland covered with floodwater as I write, the water levels will lead to lost crops, forcing farmers to write off produce that would otherwise have counted towards the UK’s economic activity. Replacements will be required for the lost stock, which may need to be imported,

Climate change cost UK consumers an extra GBP 171 in 2022, rising to GBP 192 this year. While the ECIU expects energy price rise to ease in years to come, the think tank still reckons that households have had to find just over GBP 600 for environment-related price drivers in 2022 and 2023. Dr Tim Lloyd, at Bournemouth University, argues that energy pricing is behind 59% of all UK food price rises. All over the world, drought and heatwaves are affecting basic commodities such as olive oil, canned tomatoes, sugar and rice. Food prices are rising everywhere: this is inevitable, given the way food is traded.

Fast forward to 2024 and UK voters go to the polls. Next year, six years later than promised, the UK government is promising to phase in the plant and animal checks that were a part of the EU border control infrastructure. This inspection activity does not come cheap and will be added on to the cost of importing food. Just when consumers thought things were settling down, they can look forward to an unexpected surge in the cost of imported food.

Unbearable pressure

Town dwellers in Japan have faced a rising tide of attacks from black bears, which are driven by a lack of food to venture into what were previously uncontested spaces. A story in The Guardian puts the number of casualties since April at 158 as well as two lost lives. Unlike the United States, where black bears are a constant risk for human misadventure, there is strong evidence to suggest that the bears are being driven by disruption to their normal food supplies rather than selecting centres of human activity as easy pickings for a quick meal.

Human fatalities arising from attacks by bears have figured in Japanese history for years. The museum reconstruction of the Sankebetsu episode on Hokkaido in the early twentieth century is pictured here. It came about after human incursions into virgin jungle. A conflict of interest with the formerly unchallenged top species was resolved on human terms. The current spate of bear attacks has broken a previous record high recorded in 2020, with many incidents being logged in Honshu, the largest island in Japan.

Unofficial estimates of Japan’s bear population range up at 44,000, nearly three times the 15,000 recorded officially in 2012. Without a corresponding increase in territory and food sources, there is no avoiding a state of constant conflict between species.

Feeding cities

BBC Food Programme editor Sheila Dillon talks to architect Carolyn Steel, author of the book Hungry City. Listen to Carolyn’s commentary as they walk around London on BBC Sounds. https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/b00cly4c

Sharing the Earth

The final episode of Chris Packham’s series Earth was the cue to wrap up a long awaited prognosis for the planet. Pulling no punches, Packham expressed his belief that humanity would either resolve the many threats the planet faces or disappear into planetary oblivion. Packham’s uncompromising position is completely logical: what we refer to as “the natural world” or “the industrial world” or even “the industrial world” is in reality a single space that is shared by competing interest groups. The problems we face arise from the planet’s collective inability to find ways of sharing one space. For instance society’s habit of staying up after dark created an economic demand for lighting: the routine use of oil lamps to light houses in the 18th and 19th centuries drove whales to the brink of extinction.

It is easy to talk about nature as though it exists in nooks and crannies that are somehow unsuitable for human economic activity. Humanity’s industrial intakes come from space that could just as easily be supporting other life forms. Industrial farming generates mile after mile of unvarying monoculture. There is no sustenance for wildlife such as orang utans in palm oil plantations. Yet the apes are ruthlessly hunted and killed for being a “problem” when they search for food among the serried ranks of trees that offer no suitable food for their species.

By making nature, industry, urban and rural environments aggressively mutually exclusive, the scene is set for all-out war. It is not difficult to see that if industry is allowed to declare war on nature, for instance, or for rural resources to be diverted into urban areas, the result will do more harm than good. The challenge of Chris Packham’s outlook is to identify and rationalise shared interests in such a way that life can evolve productively. The BBC Earth series is currently on iPlayer: click the screen dump to access the BBC website.

Value or price?

Today’s On Your Farm came from Yew Tree Farm, Bristol’s last city farm. Third generation farmer Catherine Withers faces existential challenges to a business that has adapted to extensive and rapid change, but is on the point of losing access to land that is vital to its survival. Part of a site of Scientific and Conservation Interest, the farm should have been spared the predatory attention of a local property developer.

Instead, acres of hay and winter feed once intended for Catherine’s dairy herd is under lock and key. The tenancy on the field concerned was terminated in favour of a planning proposal for 200 homes that has yet to be agreed. When the BBC visited, the hay in the field was ready to be cut and the livestock would have been sure of winter sustenance. However, Catherine is kept away from her crop by a heavy padlock on the gate. Being able to see the crop but not gather it in just adds injury to insult.

Elsewhere on the farm, another tenancy on a field adjacent to a local council crematorium is set to end, as the town hall plans to extend the amenities for its residents. Again, it is the dairy cattle that will lose out. Catherine has a small dairy herd, as well as outdoor pigs: she also grows vegetables, which she can sell to local residents within walking distance of her farmhouse. Bristol used to have more than 30 farms within its boundaries: as the city’s only remaining farmer, Catherine is something of a local hero, not just to her customers.

Yew Tree has a high proportion of ancient meadow in its grazing, an irreplaceable asset that has been quietly sheltering threatened flora and fauna for centuries. Its value to Bristol is incalculable, but depends on being an integrated space, across which wildlife can roam. The shift from viable and productive to long term decline is an ever-present threat and determined by factors that neither Catherine nor her many supporters can control.

Listen to the programme while it is available on the BBC Sounds website. It raises questions for all of us, regardless of whether we live in a city or a rural area.