Sky News is currently streaming an overview of British farming (https://news.sky.com/story/it-keeps-me-awake-at-night-can-british-farming-survive-13132220) which raises a number of questions that have been dodged for years and are coming home to roost with a certain inevitability. They are as predictable as ever, as intractable as ever and demand answers as urgently as ever. The only certainty is that the farming sector faces a crisis which has been ignored for years and will no longer wait in an orderly queue.

The first thing that needs to be made clear at the outset is that there is no such creature as an average farmer. The Sky presentation is very careful to choose visually tame representatives of a sector that is universally misunderstood. Sky’s lead journalist on this reporting, the west of England and Wales correspondent Dan Whitehead, would doubtless agree that despite the rapidly falling numbers of farmers in Britain, there is no such creature as an “average” farmer anywhere in the world.

The industrial world develops and markets a range of specialist vehicles and technology for a sector that has as many solutions for its many technical challenges as it has practitioners. The general public, in Britain and further afield, has no problem synthesising a stereotype notion of a nonexistent rural world. In the process, any suggestion of a viable business model runs counter current to the town dweller’s vision of a rural idyll.

It would not be productive to imagine that rural businesses are complementary to industrial or urban economic structures. Nor can the transport and distribution networks that link urban consumers to an imagined rural hinterland ever ensure that each business gets what it needs in a timely manner.

A frequent town dweller’s notion of a farm is more like a zoo than a production unit. Go back a century or so to George Orwell’s Animal Farm and you encounter a group of anthropocentric livestock: hens, pigs, cattle and heavy horses. Truth to tell, if it ever existed, this diverse community of livestock was a casualty of the first world war. The two million British equine casualties had a greater impact on warfare and industry than the loss of several millions of military personnel or civilians killed in air raids elsewhere. British army officers were required to supply a horse’s front hoof when reporting an equine casualty, whereas they did not need to furnish any such grisly evidence for human casualties among their ranks.

The wartime massacre of draft horses was beyond the breeding capacity of the northern hemisphere and cleared the way for mechanisation in both rural hinterlands and metropolitan centres alike. The British army bought in horses from as far away as North America, but they were ill-suited to military requirements.

Both agriculture and industry have exhibited huge appetites for energy during the past two centuries. The combined effects of converting the plains of North America into a grain exporter on a continental scale. This was accompanied by the relentless westward advance of the railroads through the 1850s and 1860s, hauling wheat back to the east coast and shipping it on to Europe.

The age of steam put bread on the tables of starving cities. It may even have given urban populations a passing curiosity as to where food comes from and what sort of people might produce it. But the only people that ever had contact with producers and consumers were traders with a limited interest beyond crop forecasts and spot prices. It is hardly surprising that during the intervening decades, a parallel web of dreams fed on pictures in books and magazines should inhabit part of the cultural vacuum between town and country.

Dan Whitehead’s rural narrative assembles facets of the agricultural world as a kaleidoscope might do. He starts by talking to Welsh sheep producer Rhodri, who has seen a 40% cut in his income, now shorn of subsidy. He is worried that his school age son will not inherit the family farm.

Outdoor pork producer Jeff laments the supposed passing of the British pig industry. Like many British pig producers, he believes his European counterparts are subsidised as generously as they have ever been. He can’t go into a supermarket without spotting foreign meat: pork chops from Spain, chicken from Poland and Brazil. He can sum up Brexit in one word: “atrocious”. From his farm in Kent, Jeff drove a tractor up London for a city centre protest. Like many in the pig sector, he is adamant that breeders have been thrown under a bus by a government that doesn’t care. “There’s an unfairness in British agriculture,” he argues. Looking at the deals the UK government signed with Australia and New Zealand, he might have a point.

Nearby, fruit grower Tim has built up a strawberry business valued in tens of millions of pounds. He needs a workforce of 2000 to pick thousands of tonnes of strawberries. Most of his recruits are from EU member states. When the UK was in the single market, workers could move freely with no time limits. Now they are limited to six months and have to move on regardless of whether or not they are a net gain or a net drain on their employer. Tim is frustrated because he cannot negotiate prices for his crop from a solid position.

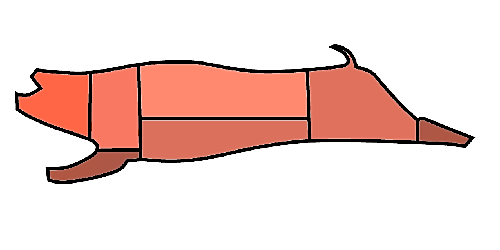

There are plenty of British pig producers who will argue that foreign pigmeat is hindering domestic producers, but the story is a little bit more subtle than that. If British producers could earn a living off the sales of pork loins, they would cheerfully do so. Since loins are used for roasting joints or bacon, there will always be buyers for this cut. This often leads to a situation whereby British loin are sold through for roasting joints. Meeting demand for bacon packers, there is a steady trade in pigs from Dutch and Danish units. These have been raised to British standards for decades and are effectively competing on a level field, even if their British counterparts see it differently. The key to staying in business is referred to as balancing the carcase, ensuring that every saleable part of the carcase is sold. Hams or gammons are straightforward to prepare for the retail market and represent a good return. What British pig breeders often overlook, however, is that they will routinely export forequarters to cutting halls in northern Europe, which have skilled workforces that make short work of the technically challenging forequarters. These are home to the animal’s powerful jaw muscles. If a pig bites your hand, count your fingers as soon as you’ve stemmed the bleeding.