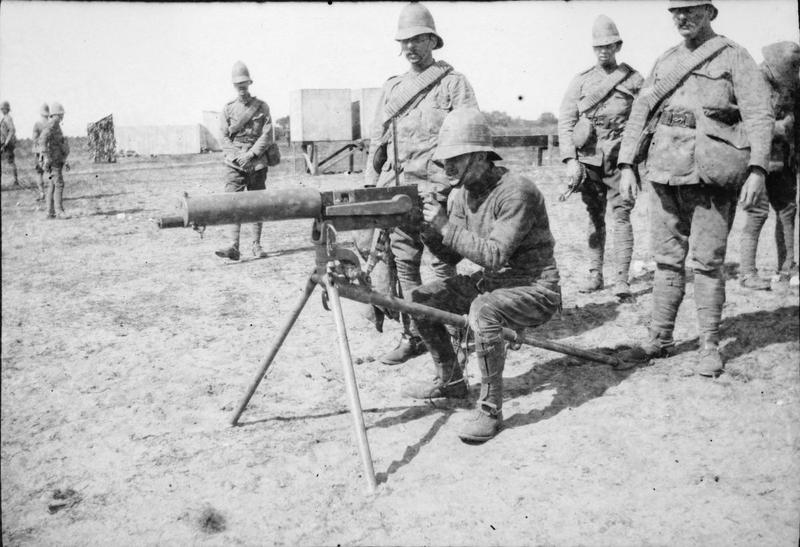

Urban Food Chains has chipped away at a series of posts on the introduction of heavy machine guns which carried out a mechanised cull of thousands of working horses and pack animals. Intentionally or otherwise, the result was to clear the way for commercial motors of different sorts on British roads. Rule of thumb loading practices for draft animal at the time would have been about 20% bodyweight. Given that the working life of a horse can be up to 20 years and you have to spend four years feeding and training them before putting them to work, there was no point in sending fit young horses to battlefields to die within weeks of arrival having realised only 0.00520833 recurring of their potential work capacity (one month, a notional average) had they lived to work for 16 years, or close on 200 months.

Urban Food Chains has chipped away at a series of posts on the introduction of heavy machine guns which carried out a mechanised cull of thousands of working horses and pack animals. Intentionally or otherwise, the result was to clear the way for commercial motors of different sorts on British roads. Rule of thumb loading practices for draft animal at the time would have been about 20% bodyweight. Given that the working life of a horse can be up to 20 years and you have to spend four years feeding and training them before putting them to work, there was no point in sending fit young horses to battlefields to die within weeks of arrival having realised only 0.00520833 recurring of their potential work capacity (one month, a notional average) had they lived to work for 16 years, or close on 200 months.

Motor manufacturers, including foreign groups which set up assembly lines in the UK (notably Ford; General Motors; Chrysler) , throttled back their car production and turned over their car lines to two and three ton lorry chassises for subsequent adaptations / personnel carriers. Their component stocks were low specificity (eg alternators to a basic spec, multiple mount options).

There was nothing particularly complicated about a WW1 pick up truck, like most new products there was a lot of workshop time to anticipate. There were 20 or so manufacturers supplying the market, including high end folk like Thorneycroft (half tracks and road/rail hybrids). The core manufacturers turned out just over 20,0000 vehicles during the war, when entry level commercial motors were 500 pounds a go. That gave the makers a combined order book of around 10 million pounds over the four years of hostilities.

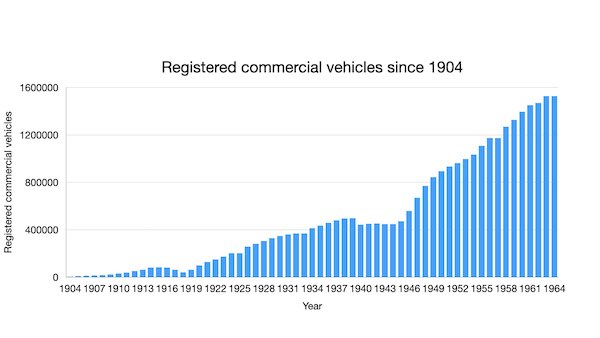

By the time the postwar economy had settled down, engines had improved in power and reliability and manufacturing margins had recovered. The world’s horse population was about 8 million less than at the turn of the century, and the conversion of agricultural businesses to new technologies was gathering pace.

Two related nuggets: when I moved to Crawley, one of my neighbours once worked as a spy for the British government while posted to the Afrika corps. His favourite anecdote was that the Ford lorries supplied to military buyers all used the same drive shaft construction. This meant that US army stationed in Europe; ae well as the relatively small number sold to Hitler’s army as well as the British army were interchangeable. Final item: Hitler couldn’t fully fund diesel powered troops on the eastern front, so he sent horse units with troops riding in a sort of sidecar. You can see them from time to time in Pathé news footage of the day.