The first world war forced ever greater rates of change than the old order would ever have imagined. Here is a collection of data curated by Christopher Turnor during the first world war and published in Our Food Supply: perils and remedies (Country Life 1916). Any prices quoted are face value at the time, without any subsequent adjustment for historical changes in value. Turnor does not go into detail on the sources of his data and its authenticity, but since he had the run of market information gathered by the Agriculture Board he is unlikely to have needed to look very far. The tables in this post are mostly scanned directly from Turnor’s book, with the intention of giving readers the opportunity to form a view on Turnor’s line of argument. I have made odd comments here or there, but I defer to the readers’ many and varied viewpoints, believing they are better served by sight of the original publication.

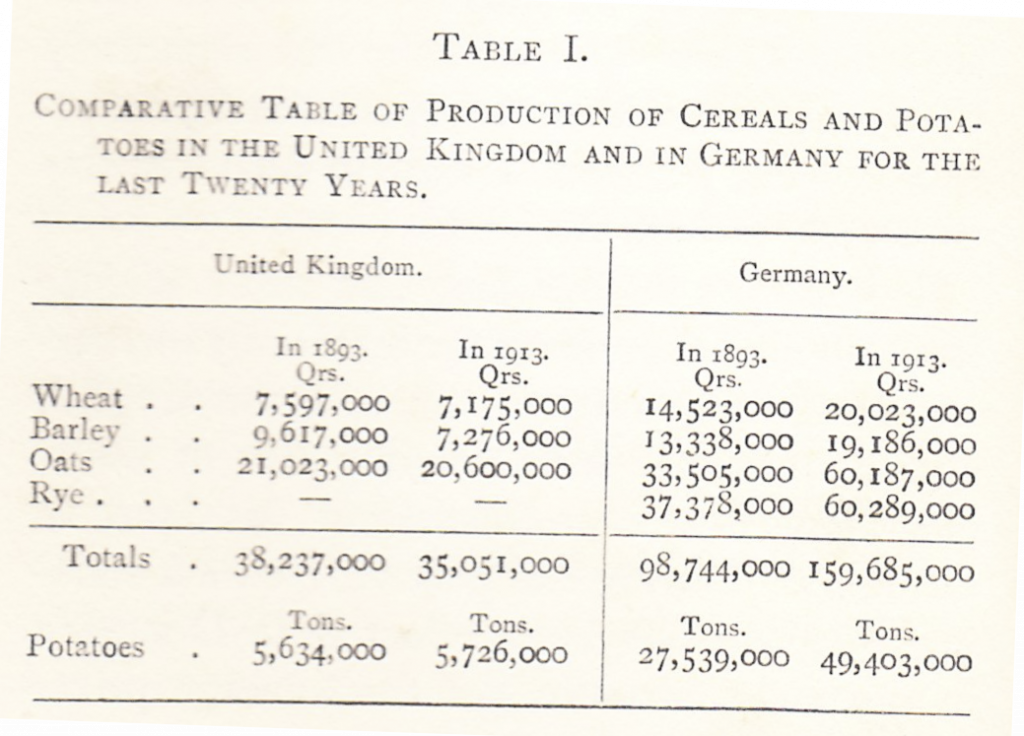

The production figures for cereals and potatoes over a 20-year time period are open to question, but the contrasting rates of change suggest that Germany had a strategic advantage in feeding its citizens over this period in its history. Sub-plot: Germany had little access to food grown in overseas colonies, so that supply chains were shorter and more effectively protected from military action.

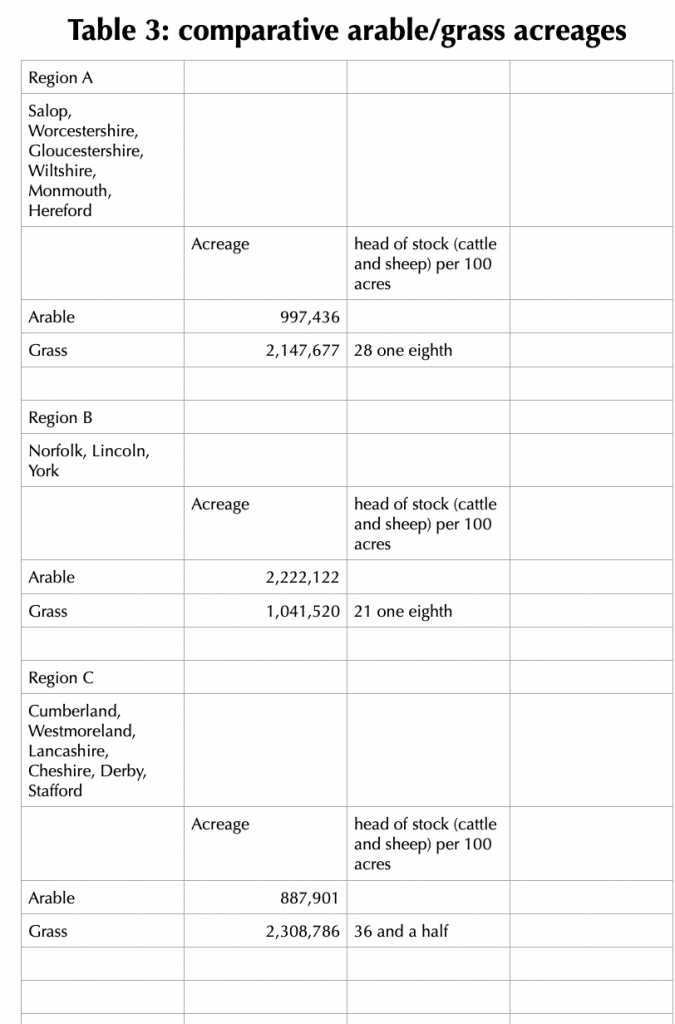

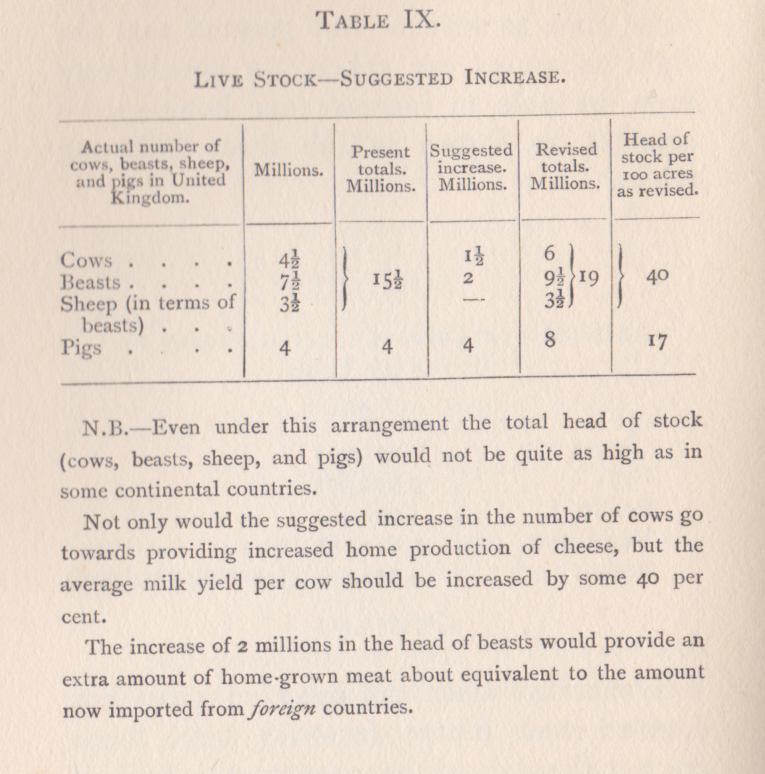

Turnor was convinced that British agriculture was being held back by a high proportion of low-earning grass supporting too few grazing animals. Here is what he wrote in 1916:

“In thinking out measures which will increase the amount of our home supplies, the permanent development of agriculture must be the aim. Attempts to increase, hastily and temporarily, the production of the soil must be ineffective and can easily be actually harmful. We must get to the root of the matter. Present conditions affecting agriculture are unsound and unsatisfactory; better ones must be created.” (Christopher Turnor; Our Food Supply, Perils and Remedies, Country Life 1916.)

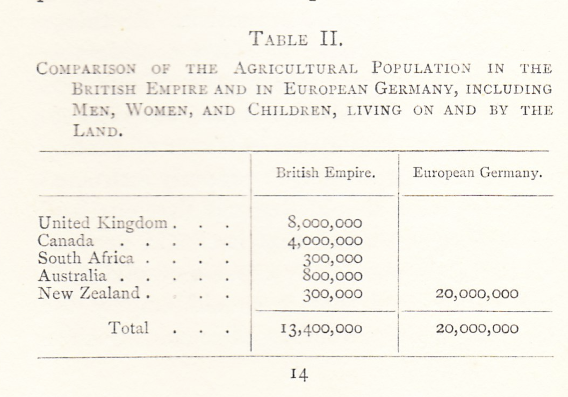

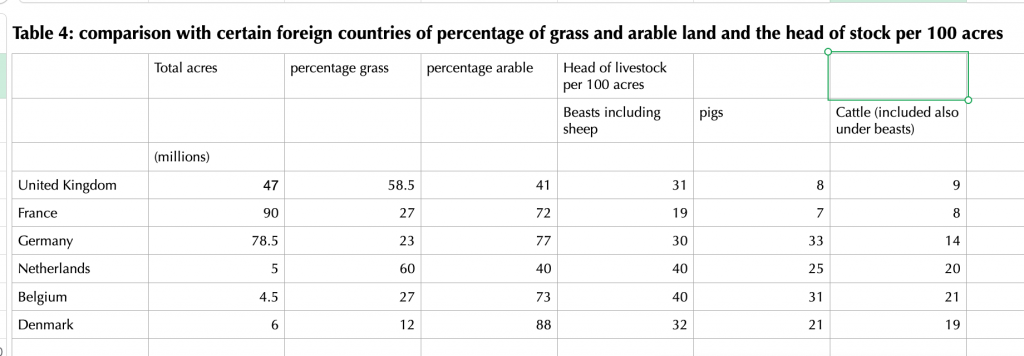

Scaling up from a county level to national comparisons, Turnor dug out the following figures during the early years of the first world war:

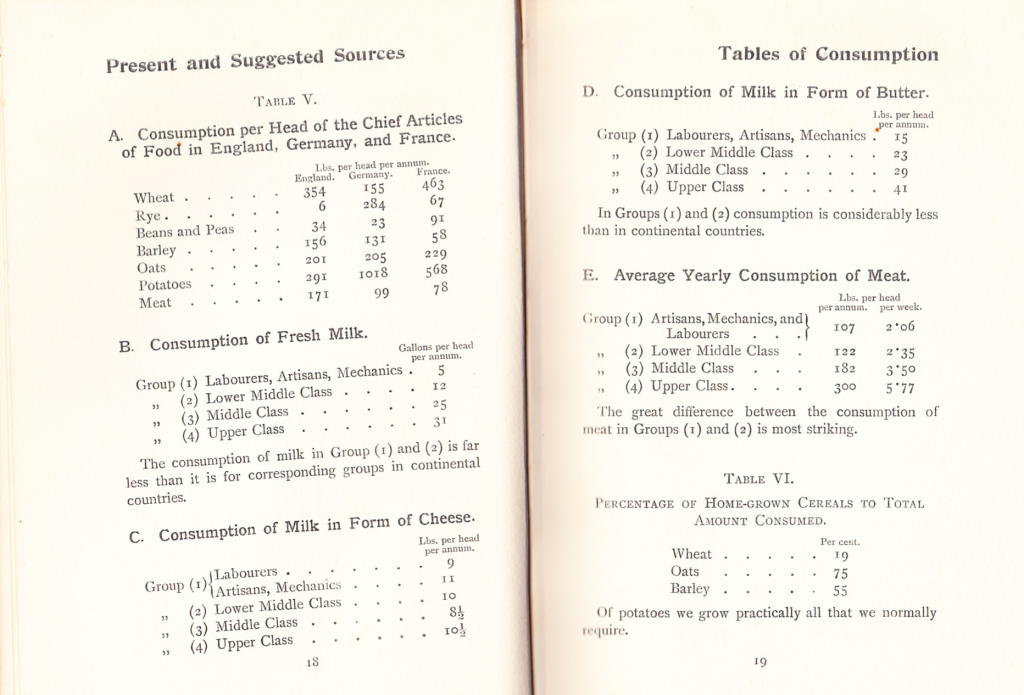

Turnor then presents a set of headline consumption figures. These classify ingredients and the opening table reflects national dietary preferences. The line for rye, for instance, identifies it as a German staple crop, and may well include sale of grain for brewing beer. A similar interpretation of barley being sold for malting would seem reasonable.

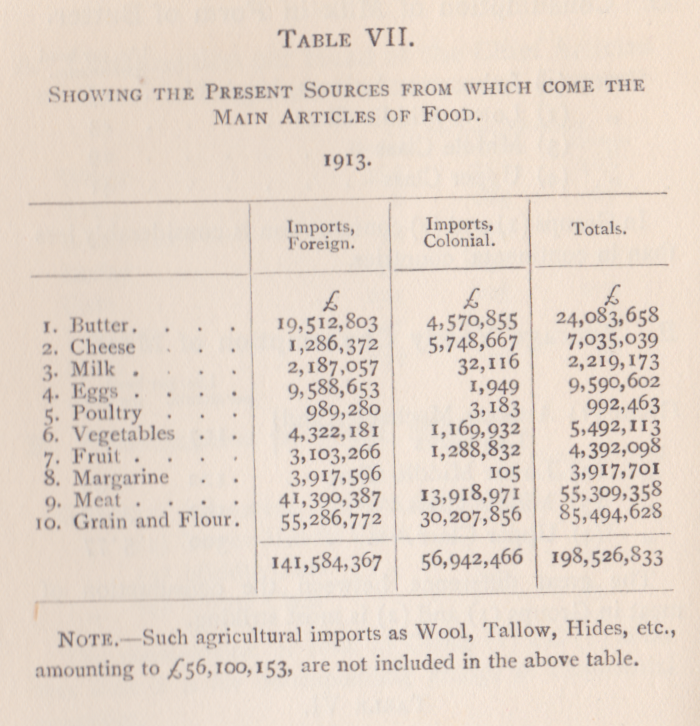

Table VII, below, sets out the cost of imported foods, probably as a set of customs values.

Stats for fifth quarter products went through the Board of Trade.

More follows

That’s it, folks.