Not long ago the Grocery Code Adjudicator’s office published its report for the past year. The reality behind the lukewarm prose is more disturbing than might first appear: the complaints raised are predictably familiar and there are multiple labels for what appear to be depressingly perennial abuses. More to the point, given the confidentiality of the process, it is not possible to determine an order of magnitude for the sums involved. This is not just a nice-to-have ballpark figure, but a true measure of the scale of a continuing problem.

The presentation and figures can be downloaded here. There are a good two dozen descriptions for the issues that have been raised by suppliers. The rates of change given for year-on-year complaint numbers are within five or six percent of the previous year, which is supposed to mean that everything is under control. The message is a very firm “…nothing to be seen here. No, really, THERE IS NOTHING to be seen here…” Yet the sort of practices that suppliers are complaining about would normally merit criminal investigations. Or would insisting on the letter of the law just put suppliers out of business?

Those who have been in the food industry for years will have acquired a collection of tales of extortion and graft that at first hearing seem overstated, but which become hard to ignore or dismiss. A lifelong food industry veteran put it this way: “The multiples have been running circles round the government for years. It’s been going on for decades. These days retailers are so used to demanding money left right and centre that it’s hard to know how they keep track of their real costs.”

It is well nigh impossible to assign an order of magnitude or give a steer on how serious the ongoing abuse might be in the grocery trade. Let us be as circumspect as possible in unpacking this one. Let us assume, for instance, that there is only one instance of a dispute under any of these headings and that the percentage figure, rather than referring to a case load, is a crude measure of the sums of money involved. Anything bolder than that would suggest a totally compromised food industry. Don’t rule that out, by the way.

Now take the following two GCA sub-headings as examples:

(a) Requests for payments to keep your existing business with a Retailer (pay to stay)

(b) Requests for lump sum payments relating to Retailer margin shortfall not agreed at the start of the contract period.

These both look suspiciously like blackmail, but let’s try to estimate an order of magnitude for these actions. Shelf money demands are usually based on a fixed sum per SKU per product range, for a listing across two to three hundred sales outlets. To get an idea of the sums of money that can be involved, assume the product concerned costs one pound and comes in five flavours and three pack sizes (sub-total 15 SKUs). Pull a pay to stay value out of thin air of GBP 5000 for each SKU listing across 250 sales outlets, fifteen SKUs times GBP 5000, guesstimate budget GBP 75000. If the retailer has a markup of 20p, the pay to stay demand is equivalent to a supplier “giving” 375,000 units of product (20p times 375,000 = GBP 75,000). While it is not unheard of for retailers to withhold all or part of an invoice, it is not in the suppliers’ interest to hand over lorryloads of product, which will earn the retailer the full retail price at the checkout: literally having their cake and eating it.

Given that a hypermarket can easily have up to 20,000 food SKUs, not counting own-label lines, you could end up with an aggregate demand for shelf money running to millions of pounds if they were all to be counted towards a shelf money Christmas list. Given that these are very large wadges of money to conceal on a balance sheet, our imaginary retailer will probably need all the accounting strategies they can think of to hide the true state of the cash flows. Again, to avoid overstatement, we will assume that each heading only refers to a single instance of a commercial abuse.

In choosing a theoretical sum of GBP 5000 per SKU for shelf money, this could be seen as an exaggeration. However, one simple factor ramping up shelf money demands is the simple proliferation of the high street formats for mainstream food retailers. It is highly improbable that a retail multiple would forego an established shelf money framework when opening high street stores. However, competing convenience stores simply do not have the kind of clout that a major multiple can bring to bear on brand owners in a store format that leans heavily on established brands.

The office of Grocery Code Adjudicator was set up about 20 years ago and spent about half that time building up its role as a trusted arbiter, a lap dog rather than a watchdog. It is hard to imagine that it has done more than scratch the surface of the very real problems facing food manufacturers and brand owners in their dealings with a clique of very powerful customers, the multiple retailers.

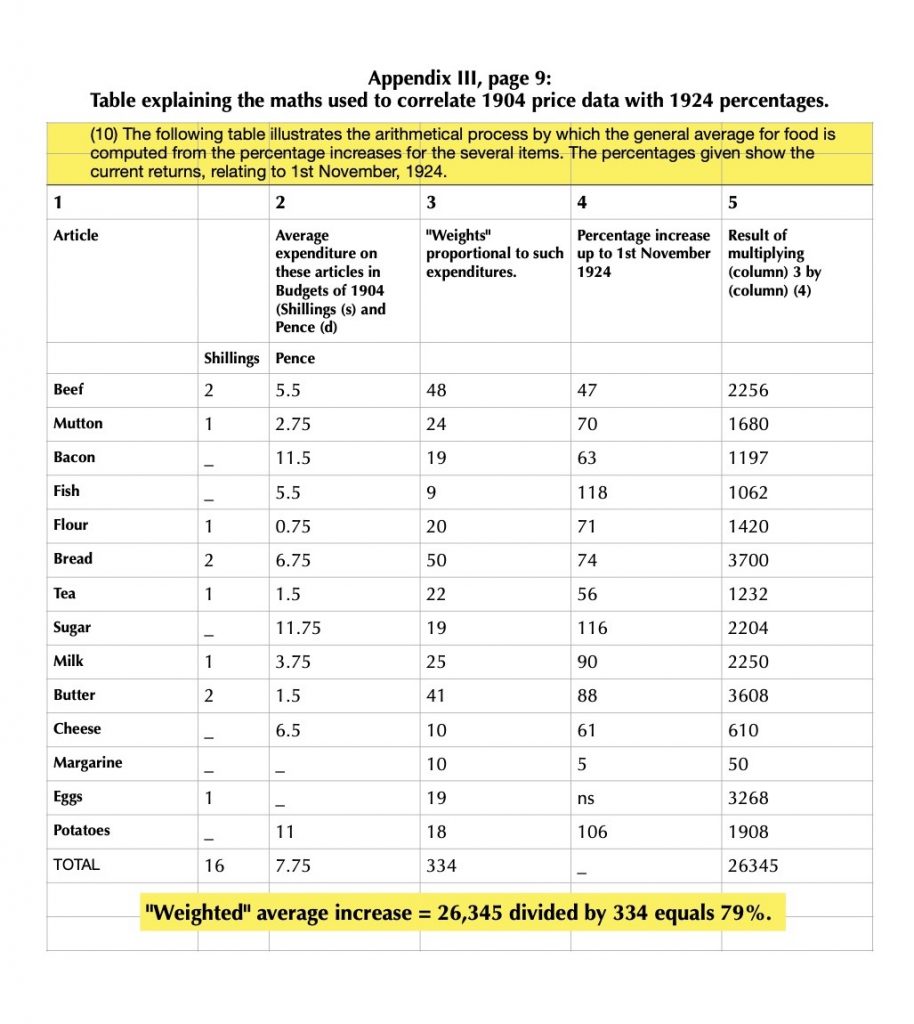

The biggest challenge that faces traders of all descriptions in arriving at a reliable price structure is the speed at which food products can change. Some animal products undergo a series of changes from farmgate to end user, others barely change at all. Some foods deteriorate very fast, while others are stable; add to this processes such as grading and the scope for differentiation can spiral out of control. For a comparison to be usable, the items need a number of similarities, bearing in mind that not all users will have the same interests. At the risk of keeping alive a business myth, there were some retailers who chose to take a cut in their margins rather than push up prices. Some individual members of of the Linlithgow committee would have been very well informed about specific markets and sector, but less inclined perhaps to share.

The biggest challenge that faces traders of all descriptions in arriving at a reliable price structure is the speed at which food products can change. Some animal products undergo a series of changes from farmgate to end user, others barely change at all. Some foods deteriorate very fast, while others are stable; add to this processes such as grading and the scope for differentiation can spiral out of control. For a comparison to be usable, the items need a number of similarities, bearing in mind that not all users will have the same interests. At the risk of keeping alive a business myth, there were some retailers who chose to take a cut in their margins rather than push up prices. Some individual members of of the Linlithgow committee would have been very well informed about specific markets and sector, but less inclined perhaps to share.