Own label instant coffees are made with the same sort of coffee beans as their branded counterparts. The only difference is that the retailers control the pricing and, as retail brand owners, they are not held to ransom for shelf money. The Consumer Association magazine Which? is advising readers to switch to cheaper own label alternatives. To stand up its story, Which? gives the example of a 200g jar of Nescafé Original, which was selling for five and a half quid in supermarkets last year and is now the thick end of eight quid a pop on Ocado. Given the scale of Nescafé’s economies of scale in the procurement and manufacturing stages, how does one explain a 30% year on year price rise? Sure, the beans are more expensive, but what does the future hold for premium home delivery shopping channels?

Waiting for salvation

All around the Mediterranean and across southern Europe, thousands of communities are waiting for this year’s olive crop to be milled. Until this year’s production is ready for packing, no new business can be written: there are no reserve stocks available. Every last litre has been sold and there will be no olive oil to sell before the first deliveries of the new crop year reach the market.

For months bulk olive oil prices have been sky high. As recently as August, some desperate buyers in Spain were paying almost 7,000 Euros a tonne for low-grade lampante that would normally have been a fraction of today’s prices. In August, the Spanish industry was forecasting a crop of 1.4 million tonnes of olive oil this year. This “business as normal” bravado is misplaced, since hot weather in the final weeks before the crop is gathered will affect the moisture content and can reduce the yield. In previous years, yields of 20% were average: but until this year’s crop reaches the mills, there is no reliable way of predicting finished tonnages. However, apart from wildfires, there is probably not a lot of additional damage that the environment could inflict on the nation’s olive groves.

The Spanish government is responding to the crisis by cutting VAT on olive oil from 5% to 4%, with effect from 2025. Consumers have seen retail olive oil prices rise from around EUR 3 / litre two or three years ago to hover around EUR 10 / litre now. The unthinkable is happening and Spanish consumers are buying sunflower oil instead of olive oil for home use. Since many households buy cooking oil in small quantities very often, Spaniards have suffered more from the rising prices than elsewhere in Europe. This is because most European retailers place huge orders immediately after the harvest is in, to cover the coming 12 months sales. This fixed price for the year means that retail bottle sizes can have stable prices for the duration, although there is a temptation for retailers to raise olive oil prices anyway, pushing up their margins.

Spain has imported 20,000 tonnes of olive oil this crop year, bringing Spanish consumer consumption and industry intake to a total of 100,590 tonnes. Bottler stocks in August were at an all-time low of 131,740 tonnes with a further 138,660 tonnes held by co-operatives and millers. Total production at the close of this crop year is expected top 820,000 tonnes, making it a poor year. An average season these days would be somewhere between one and two million tonnes of oil.

This year saw a closing of the gap between Extra Virgin Olive Oil (EVOO) and cheaper grades. Paradoxically, strong demand for better grades meant that the market was picked clean, leaving mainstream buyers to pay more for lower quality grades because that was all there was left. Formerly used to fuel oil lamps, as the name suggests, today lampante refers to oil that needs work to return it to an edible grade. This means that lampante has a limited number of takers, since the consignment will need to go to a refinery, adding to the cost and commercial risk.

Mind the gap

International olive oil packers face a very real threat of gaps in stocks of olive oil before this year’s harvest comes onstream. There is reason to believe that without any carry-in stocks, the scenario will be repeated next year. Prices have been high for months, as dwindling tonnages have been shipped from emptying tanks. Costs are not expected to ease before May 2024. This is an unprecedented situation, even to the industry veterans who remember the 1990s.

The Turkish government has banned bulk shipments of olive oil until November 1, as Italian and Spanish packers scoured the markets for available tonnages. The 2021-22 crop year came close to 230,000 tonnes of olive oil in Turkey, while official sources are predicting a record 400,000 tonne crop for the current crop year. The country has a large table olive sector, which is also expecting a bumper crop of 700,000 tonnes. The way the two harvests are managed reflect the different product requirements, but variables such as oil content and moisture content have a degree of wriggle room. Table olives are fragile and demand very careful handling to remain visually perfect, while olives bound for the pressing mill need to be intact but not necessarily pristine.

Turkey also produces three quarters of the world’s hazelnuts, with average crops of around half a million tonnes inshell equivalent in recent years. There are lingering memories among olive oil traders of instances when consignments were topped up with hazelnut oil, which is very hard to detect when mixed with olive oil in small quantities. Such adulteration introduces a nut allergy risk, proportional to the percentage added. It requires specialist laboratories using either chromatography or spectroscopy to detect it. The confident predictions of record olive oil tonnages in Turkey’s current crop year may not be completely fortuitous.

In June, Portugal’s producers were predicting a trend-busting crop topping 100,000 tonnes, maybe even a record 126,000 tonnes. Whether it turns out to be a record harvest or not, it will all sell through in very short order. There is reason to suppose that the country is benefiting from its extensive Atlantic facade, even though Portugal is not a major producer.

Normally a net importer of olive oil, the southern hemisphere olive oil producer Ecuador is preparing to empty both its harvest and its reserves into a transient seller’s market. In terms of tonnages, this is unlikely to top 3,000 tonnes The southern hemisphere crop is in its final stages this month and every tonne harvested has a number of potential buyers in Europe.

The growing concerns over olive oil supplies are surfacing in many different ways across southern Europe. Croatian olive oil producers are critical of the restaurant trade’s insistence on putting cheaper imported olive oils on tables, while local specialities are promoted on the menu. Award-winning olive grower Ivica Vlatkovic put the cat among the pigeons by urging restaurateurs should sell 100 millilitre bottles of good quality olive oil as part of the cost of a cover.

Burning question

Wildfires across huge areas of southern Europe mean even more bad news for olive oil and table olive packers. It is impossible to predict the full effect on this winter’s prices for olive oil or table olives, but there will be direct consequences. This is not a complete wipe-put story, since established olive trees with deep root systems can recover from fires, although this will take time. Young olive trees are more susceptible to fire damage.

The immediate impact will be on packers and blenders of olive oil, particularly in Italy: these skilled folk have a network of suppliers for very specific oils with relatively rare qualities. The suppliers of such rarities are spread over the continent, from Gibraltar and north Africa down to the middle east. The trading network is complex and known to a handful of olive oil blending experts.

In a year when the mainstream crop is already looking patchy and fraught, this will mean higher costs for the retailers. In the UK, the multiples are reluctant to let their double digit margins take a hit and will do their level best to make sure that suppliers carry the burden. The situation is, however, beyond horse trading. Bulk olive oil prices will be non-negotiable, where there is product to be had. Looking at the Mediterranean over the next few weeks, the following impacts can be expected. Industrial tomatoes for peeled plum tomato canning lines can be expected to be short, since crop irrigation is being used for firefighting. Chopped tomatoes, passata and tomato paste can be made from almost any variety of tomato and production is not limited to southern Italy. Table olives are under a shadow, with a high risk of localised damage: a lot of olives will have been burnt off the trees. Durum wheat, essential for pasta manufacture, may have escaped the worst of the heat waves, but export tonnages will probably be restricted.

For the latest information on the European forest fires, click here.

Growing demand

Total imports of Spanish olive oil to the UK topped 92,000 tonnes in 2021. That includes retail products, industrial, pharmaceutical, food manufacturing and UK-bottled own label product. The only tonnage it leaves out is olive oil sold by Lidl and Aldi. That represents a lot of demand for physical stock. Over the past decade it has climbed from 70,000 tonnes, with a wobble caused by high fuel prices in 2018.

Olive oil by numbers

The UK has been a strong market for olive oil in recent years, in a world where consumers are spending more than 14 and a half billion pounds a year on the Mediterranean’s most important crop. UK consumers will be paying rather more than their European neighbours in the coming months. They already pay over the odds, as it is.

The UK market caters for small introductory purchases: 250ml bottles currently retail for GBP 2.45p for olive oil, GBP 2.55p for EV (Sainsbury on June 1), while a Tesco 250ml bottle of bland mild and light olive oil has risen by 18% over the past year to GBP 2.83p. Tesco pricing for a litre of leading brand EV has risen steadily over the past 18 months by 50% from GBP 6.95p to GBP 10.40p, while ASDA increased the shelf edge price for the same branded litre of EV from GBP 6.50p to GBP 8 on June 1.

As of June 1, the ASDA shelfedge price for a one litre bottle of Filipo Berio EV went up to GBP 8, while Tesco was asking GBP 10.40 for the same product. It is safe to suppose that ASDA was not selling this line at a loss. So “every little helps” Tesco is charging 30% more than its rival. The day before, the differential was 60% for the same stock on the same shelves in their respective stores.

At a nearby town centre branch of Iceland during the same store check, the olive oil category was a one liner in every sense of the phrase. It comprised a single SKU, 500ml of ordinary olive oil for £4 in a tertiary brand, packed in a tidy plastic bottle. A no-frills distress purchase.

UK grocers selling olive oil have been milking the category. Spanish consumers get through a per capita average of 10 litres a year. They know what it’s worth and expect to get value for money. At the moment, headline olive oil prices are rising and are close to EUR 5,500 a tonne for EV grades. UK retailers will have to rethink their margin expectations if they are going to secure product and continue selling it. The party’s over, guys.

Rules Of Origin (ROO)

Goods that combine components from more than one trading bloc are subject to the Rules Of Origin procedure. Goods made in the EU are zero-rated on arrival in the UK, while the status of duty payable on third country components or ingredients used in EU goods is determined by applying Rules Of Origin. These establish whether or not the third country component has been transformed sufficiently for it to be considered an integral part of a new product. If it is a fellow traveller in a blended product, for instance, it is liable for duty.

The first target is to ascertain whether or not the component concerned has been absorbed into the finished EU product. If so, it can usually be covered by the duty payable on the finished product. If, on the other hand, it can be recovered from or identified within the EU product, the third country component may be liable for third country duty pro rata. The key marker is whether or not the third country component qualifies for a change of customs code. This will be decided by the UK customs staff on a case by case basis.

In the case of third country extra virgin olive oil (1509 2000), it is considered a fellow traveller in a blended product. This currently stands at 104 gbp per 100kg, according to the UK government online tariff service, https://www.trade-tariff.service.gov.uk/subheadings/1509200000-80 (as of check made on May 29).

Olive oil stocks under pressure

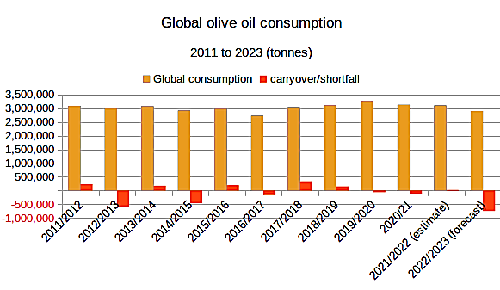

Spain, the world’s largest producer of olive oil, faces the prospect of running out of extra virgin olive oil in the coming months. According to industry figures seen by Urban Food Chains, forecasts for worldwide consumption of olive oil are expected to drop from 3.1 million tonnes to 2.9 million tonnes in the current campaign. There is a potential shortfall of 745,000 tonnes worldwide.

The Spanish industry invested heavily in extensive tree plantings around the turn of the century, with enough trees and crushing capacity to produce one and a half million tonnes of olive oil in a season. But the 2022-3 crop was a poor crop and down by over 50 percent against the previous campaign. This year a lot of flowers set on the trees, but like last year, the trees are stressed and are shedding the fruit.

With total olive oil stocks across the Spanish industry hovering at just over 607,000 tonnes, the sector faces empty tanks later this year. Domestic consumer demand is strong and April sales in Spain topped 63,000 tonnes. With at least six months to go before the next harvest comes onstream, Spanish consumers will be competing with exporters for physical stocks of olive oil.

Demand is strong and prices are high but expected to go up even further. Assuming that Spanish consumers ease up on their purchases of olive oil, which is not a given, a 5% drop in month on month sales volumes would represent a requirement of just over 277,000 tonnes between now and the next crop. The Spanish industry delivers shiploads of olive oil around the world and all over Europe by tanker truck. Exports as of around 50,000 tonnes a month would empty the country’s remaining stocks by November.

Like any other crop-driven commodity, there is a numbers game in play and prices will rise steeply to head off strong demand. Retail margins will come under pressure as physical product becomes harder to obtain. The EU has trade deals with north African producers, who can ship quota tonnages that member states can draw down with zero duty. Should any of this third country olive oil be packed for the UK market, even in a blended product, Rules Of Origin (ROO) would apply on arrival at the UK frontier, where duty would be charged on the non-EU content.

But the underlying concern has to be the drying out of water tables across a huge swathe of southern Europe and the Mediterranean basin. Olive trees have deep roots, but not deep enough, it might seem. In Spain, the planting of thousands of trees has propped up crop yields most years, but not all. This year’s forecast being a case in point.

Dietary gold on trees

Today (Friday November 26) is World Olive Tree Day, as growers in the northern hemisphere prepare to pick the next crop of olives. More than two thirds of the world’s olive trees grow in the Mediterranean basin and survive thanks to their deep roots. Younger trees planted in more recent groves will often be irrigated until their roots have reached cooler, damp rock formations.

Olives are a winter crop: starting in November unripe green olives are gathered and pressed for distinctively strong, green oil. As the winter progresses, the olives darken and ripen, the oil changing to gold as the flavour softens with the fruit. The harvest continues into February and March, depending on varieties and locations.

Traditional olive-picking techniques needed the olives to be hard enough not to break up as pickers beat the trees with heavy sticks. Today, large groves are harvested with a mechanical arm attached to the trunk of the tree. The tree is then shaken vigorously, emptying the fruit onto large sheets spread out to catch the crop. The process is stressful for the tree, but is quicker than the stick-wielding villagers. The remaining winter months are a time of recovery.

Once picked, olives are fragile. Away from the tree, the olives start to accumulate free oleic acid as they oxidise during the different stages of processing. Only when the oil is extracted and stored under nitrogen can the oxidation be halted. The largest pressing plants, typically in Spain, where batches are consolidated and have more time to oxidise, face the prospect of minimising the effects as best they can.

Olives picked for the table have an additional constraint: unlike olives bound for pressing, every table olive needs to be visually perfect. To remove the stones from olives, the flesh needs to be firm and the olive must be unripe. To produce black pitted olives, green olives are treated to make the flesh black and then the stones can be removed mechanically. By the time an olive has fully ripened and turned black naturally, it is no longer possible to remove the stones mechanically, since the soft flesh just falls apart. The taste, however, is exquisite.

Olive oil grades

Olive oil is a highly-prized commodity, for a very wide range of reasons. As a key ingredient of many elements in the Mediterranean diet, it is a pivotal component of Mediterranean cuisine. Across the region, household use of olive oil would be counted in dozens of litres a year.

Spain is the world’s biggest producer and user of olive oil: collectively, domestic consumers buy tens of thousands of tonnes every month. The country usually produces over a million tonnes of olive oil a year, much of it shipped to packers all around the world.

Greek olives are harvested in small quantities and pressed within hours of coming off the tree. Domestic Italian production is an even lower tonnage. Italian blenders are very skilled at procuring the right mix of flavours and colours of oil from all over the world to blend in bulk. The bottles were often marked “Prodotto in Italia” (“produced in Italy”) but this delightfully vague ambiguity was outlawed by the European Commission.

Pressing yields anything up to 20% by weight in oil. This ranges from the cheap and cheerful institutional canteen cooking oil, olive pomace oil, through to single estate, single variety specialist extra virgin olive oils containing less than 0.08% in free oleic acid. Like wine, the estate bottled oils are like an exclusive club: they are as distinctive as the groves they came from.

The next grade, virgin olive oil, will have less than 2% free oleic acid, which will be reflected in the taste. The different grades of virgin olive oil are too delicate to be suitable for deep frying, which is the main use for olive pomace oil. Pomace is the paste that is left over from the mechanical pressing process used to extract virgin oil grades. Due to its lower moisture content, olive pomace oil is better suited to high temperature applications.