There is a streak of unpredictable whimsy that runs through English high society from Georgian times up to Victoria’s accession to the throne and beyond. It was aggravated by conventions that made no sense and dug ever deeper chasms between the aristocracy and its servants. Take the brutal economics of keeping a horse in cities, large or small. It was generally reckoned to cost upwards of £300 a year per steed, looked after by specialist staff, some of them issued with uniform that cost more than their wages, even after allowing for any board and lodging found by the employer.

Town-dwelling horses were kept in grouped stables, or mews, usually bearing the name of the street they served. The equine diets were the standard fare of working horses of the day: hay, oats and roughage, washed down with water at intervals. Horses were the prerogative of the very rich or tradesmen who could cover their outgoings from their business. Agricultural businesses occupied the middle ground in this polarised rule of thumb scenario. The more successful ones worked with established lines of Percherons, Cobs or Shires, often breeding their own draft animals and systematically avoiding the saddle horse fraternity.

Town-dwelling horses were kept in grouped stables, or mews, usually bearing the name of the street they served. The equine diets were the standard fare of working horses of the day: hay, oats and roughage, washed down with water at intervals. Horses were the prerogative of the very rich or tradesmen who could cover their outgoings from their business. Agricultural businesses occupied the middle ground in this polarised rule of thumb scenario. The more successful ones worked with established lines of Percherons, Cobs or Shires, often breeding their own draft animals and systematically avoiding the saddle horse fraternity.

There was no missing the fact that horses scaled up the waste disposal problems associated with urban lifestyles. Dung disposal alone was a significant challenge, to the point where the city of London filled at least two barges a day with sweepings from the city’s crossings, which went down to the Thames estuary under cover of darkness to dump good quality, nutrient-rich material at sea.

Clearly, today’s environmental issues have deep roots: they were taking shape in the Thames estuary and elsewhere around our coasts, long before the arrival of the automotive age.

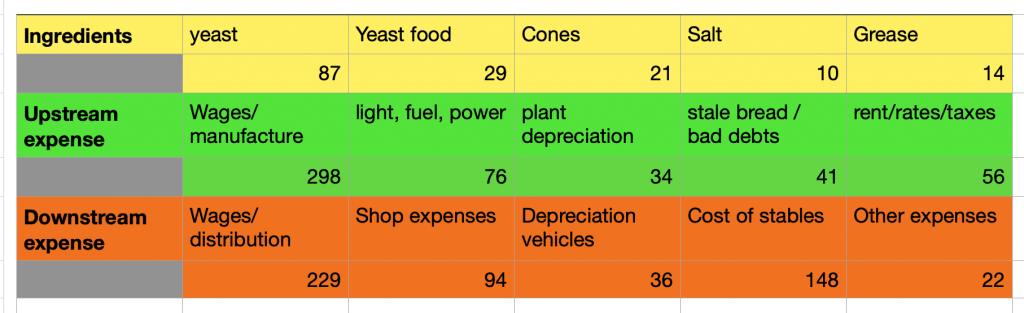

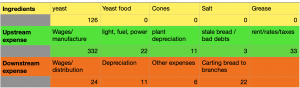

The Linlithgow committee provided four business snapshots based on live data (1923 figures..) to illustrate how the sector operated. There is no way of telling how much m, but the ones they published cast some light on the baking sector. Only theWar Office refused to share any data. The most detailed is based on figures from the National Association of Master Bakers’ and a number of local associations. The Industrial Co-operative group gave a terse rendering of the Co-op’s pricing structure, which differs in smalll but significant ways from retail rivals. Third is a glimpse of the War Office bakery, in Aldershot. It went to extraordinary lengths to say nothing. For the time being, I cannot locate where Butler Brothers traded, but the firm operated a number of branches from a central bakery.

The Linlithgow committee provided four business snapshots based on live data (1923 figures..) to illustrate how the sector operated. There is no way of telling how much m, but the ones they published cast some light on the baking sector. Only theWar Office refused to share any data. The most detailed is based on figures from the National Association of Master Bakers’ and a number of local associations. The Industrial Co-operative group gave a terse rendering of the Co-op’s pricing structure, which differs in smalll but significant ways from retail rivals. Third is a glimpse of the War Office bakery, in Aldershot. It went to extraordinary lengths to say nothing. For the time being, I cannot locate where Butler Brothers traded, but the firm operated a number of branches from a central bakery.

This could not come too soon, as inter-war businesses set about restoring their delivery systems. When trying to track the development of value in the pricing of bread and bakery goods, the editor of Industrial Peace, Major W Melville, conceded that the public grasp of the price structure was “little understood”. The only accessible estimates came from the Linlithgow Report and started outside bakeries with the purchase of sacks of flour. From the plains of north America, the vast expanses of Australia, to the more modest arable holdings of England, Linlithgow collects the entire growing stage of breadmaking flour into a single undifferentiated lump.

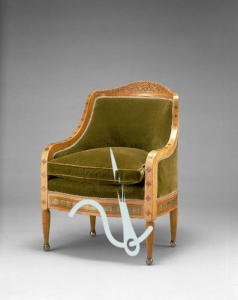

This could not come too soon, as inter-war businesses set about restoring their delivery systems. When trying to track the development of value in the pricing of bread and bakery goods, the editor of Industrial Peace, Major W Melville, conceded that the public grasp of the price structure was “little understood”. The only accessible estimates came from the Linlithgow Report and started outside bakeries with the purchase of sacks of flour. From the plains of north America, the vast expanses of Australia, to the more modest arable holdings of England, Linlithgow collects the entire growing stage of breadmaking flour into a single undifferentiated lump. The opening pages of the Charié report (vol 1, p17) carries a parallel message, likening a distortion of competition to a pin left behind in an armchair. No matter how well-appointed the chair, a single pin can render it unuseable. (montage: Urban Food Chains)

The opening pages of the Charié report (vol 1, p17) carries a parallel message, likening a distortion of competition to a pin left behind in an armchair. No matter how well-appointed the chair, a single pin can render it unuseable. (montage: Urban Food Chains)