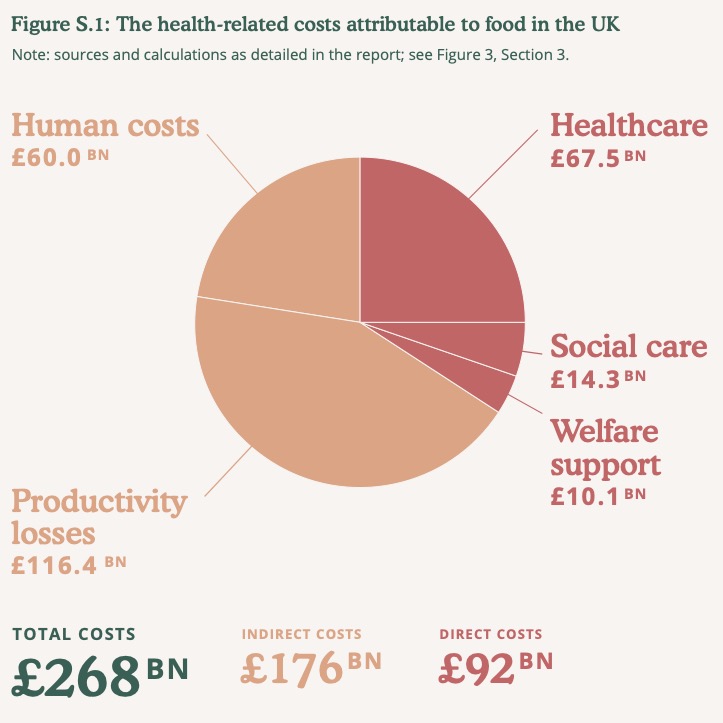

The impact of Government policy to improve the national diet comes with proportionally higher costs for poor households. This would apply to any government, of any stripe and any motivation. Structural change in food policy throws differences in earnings into sharp relief. When the Food Standards Agency published the Eatwell Guide in 2016, a headline price rise of £38 a week would mean a doubling in food bills for poor households, compared to increases of just over a third for affluent consumers. Using Eatwell data on a national scale, the Food, Farming and Countryside Commission (FFCC) researchers calculate that legislating for a healthy, sustainable national diet would come with a £57 billion price tag. This is not unreasonable, indeed it is good value, given that the direct cost of healthcare arising from diet-related illness is running at £91 billion, lost productivity is costing the economy an estimated £116 billion a year and the human cost a further 60 billion a year. The numbers basically accuse the food industry of being more interested in making money than feeding people. However, the scale and scope of the money extracted from UK health authorities by pharmaceutical corporations is several orders of magnitude greater and no less reprehensible.

If the market economy functions as one might have hoped, would this ever have occurred in the first place? Part of the problem with economics is that its practitioners quite cheerfully play “what if?” games as they go along. The problem is not that a variable might be unreliable, but that the outcome can change in so many ways that it is impossible to attribute a given outcome with a single input. Treating the food/health sectors as a series of events, for example, creates a dislocated view of the biosphere, with more gaps than development. Some gaps are inevitable, but you can have too much of a good thing.