Towards the end of the twentieth century, the UK was importing about a quarter of a million tonnes of cheese a year.

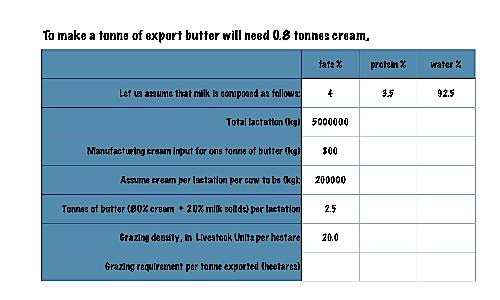

Butter by numbers

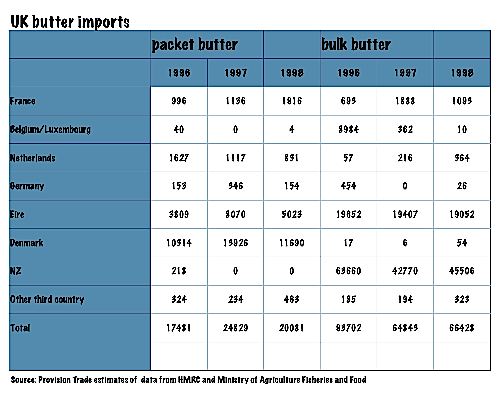

A cow producing 5000 litres of milk in a lactation (a lot by the standards of the 1990s) would give enough cream for two and a half tonnes of butter. Converting the remaining output into skim milk powder (SMP) would add a further couple of tonnes of powdered milk to the final output. There are other ways of splitting up milk fractions, some of them with limited use and application. Some standard variables appear in the first table, while the second outlines UK butter import tonnages for packet butter (retail product) and bulk butter for 1996-8, when the Common Agricultural policy was in full swing.

Taking the 1998 total packet butter imports total of just over 20,000 tonnes and when the total is divided by 2.5 (tonnes per lactation) it becomes clear that you will need at least 8,000 lactations — or lactating cows — to generate this tonnage. Bulk butter imports for that year topped 66,000 tonnes, needing a further 24,000 cows. Figures on this scale pose two serious questions.

First, is the UK economy capable of generating sufficient demand to increase domestic production by a comparable tonnage? Second, where would the UK accommodate an additional 30,000 dairy cows and the same number of calves that would trigger the necessary lactations? The chances are that the UK economy is not vigorous enough to generate investments in domestic production on that sort of scale. It is equally probable that the UK landscape would not absorb thousands of additional cattle and their calves.

The attraction of imported stock such as bulk butter is that it can be diverted into seasonal products like mince pies, which are planned into shifts after Easter and stored in a freezer until needed in the run-up to Christmas. Energy prices have made this pattern uneconomic this year, but it was a successful venture in previous years.

Butter comprises 80% cream and is transported in a refrigerated system. If there is no refrigeration, butter can be clarified. The process removes the water and heat sensitive protein, turning it into ghee. This can be kept in hot climates at ambient temperatures.

Milk by numbers

Milk is around 90% water, so it makes sense to stabilise it as butter or cheese or milk powder before trying to move it anywhere. A good example would be New Zealand, which has a network of butter/skim milk powder plants, where milk is centrifuged to extract the cream. This is made into butter, while the remaining skimmed milk goes to a drying tower and leaves as skim milk powder (SMP).

The UK has a tradition of marketing its milk as liquid milk, which is either pasteurised, sterilised or put through an Ultrahigh Heat Treatment (UHT) line. UHT cartons will have a life of around a year at ambient temperatures, sterilised milk should be protected from the light, but will last indefinitely in unopened bottles.

Using a centrifuge, milk for pasteurisation or UHT lines will be standardised at 4% or 2% or zero percent for full cream; semi-skim or skim respectively. Surplus cream is usually collected in a tank for sale on the industrial market. A milk packing plant can quite easily generate a tanker load during the course of a week, for most of the year, with the exception of a Christmas peak in UK sales of cream. Before Brexit, tanker loads would often travel as far as Germany and be a viable proposition.

Milk powder footnote

All milk for powder making must be centrifuged before it goes through the drying tower. Any remaining cream or protein would block the fine nozzles used to spray the milk into a rising column of hot air. The fat-free Skim Milk Powder is collected from the bottom of the tower.The fat content is restored if there is a need for Whole Milk Powder or a custom formulation for food manufacture or baby foods.

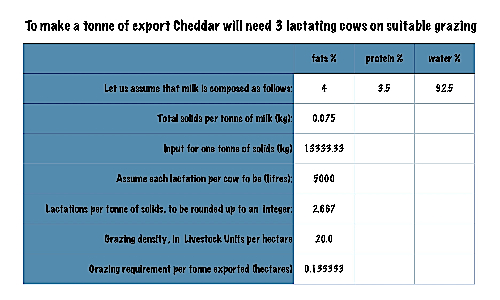

Cheese by numbers

When you come to realise that milk is made up of water — 90 percent or more — it becomes clear that it needs to be turned into something a bit more user-friendly to be transportable. Making cheese has routinely been a convenient way of stabilising fragile milk and preparing it for a longer journey to its end user. Milk proteins will be retained and a proportion of the cream will be either removed or additional cream will be added, depending on the recipe. Cheddaring cheese is basically a technique for extending the working life of milk, using the existing solids. The progression is laid out in the table below.

Having made curd with the milk, there is inevitably some loss of the finely divided protein particles that are retained in the whey. The whey was traditionally fed to pigs, which is why the history of livestock farming in Denmark was so closely integrated. A significant component of Danish bacon in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries started out as whey from cheesemaking.

Depending on the density of grazing livestock — the example here assumes 20 lactating cows to the hectare — there will always be a certain amount of agricultural land that will be blocked from local use by the commitment to export the production it supports. This is a topic to which we will return. For now, it is sufficient to assume that dairy producers will need three lactations (integer values) for every tonne of milk solids that are recovered and transferred into cheesemaking. In addition, there will be a need for three twentieths of a hectare of grazing land to meet the Livestock Unit level in this model.

There is a greater diversity among cheeses, reflecting their moisture content and how the whey is removed during the cheesemaking process. As a cheese ages, it will go from being a crumbly wet curd and solidify into increasingly dense cheeses. Whole cheeses are matured for up to two years in the case of hard cheeses like parmesan or Grana Padana, a year or more for mature grades of Cheddar, to just six weeks for soft cheesses like Camembert or Brie. The protein can be more or less elastic, depending on how much heat has been applied to the curd and other factors in the process.

Milk prices set to take off

The farmgate milk price has risen by nearly 24% during the year ending March 31, 2022. For most of this time, prices tracked the five-year minima, but started to rise steeply from January and into February, closing the gap on five-year highs as the spring flush appears on the horizon. This is the time of year when the majority of UK dairy farms plan for calving, since there is usually strongly growing grass and the longer days promise more favourable weather for the next generation of cattle.

With a high proportion of cows starting a lactation in a normal year, milk volumes would go up, reaching a peak later in the summer. A slower start to the spring flush is a marker for a more difficult year, while the rising farmgate price gives cause for concern, since it would suggest that there are fewer lactating cattle to supply the market.

There is, however, another factor that will push producer prices up. The UK dairy industry has a lot of milk tankers on the road and unprocessed milk is a high mileage market. Steep rises in fuel costs will also impact the headline producer price of milk. source

Producers get a grip on their markets

Pig sector still struggling

Despite some welcome signs of change in the fortunes of the pig industry, there are some ominous long term indicators. slaughter weights are starting to ease off from January’s high point. But at about 94kg deadweight, this year’s slaughter pigs are still five kg a head more that this time last year.

Welcome news from Morison’s when the retailer raised its contribution to production costs (SPP) by 30p to GBP 1.80. Pig producers need more retailers to do likewise. More to the point, producers need a more reliable system for recovering their cost of production, just to stay in business.

January pigmeat imports totalling 83,000 tonnes were up over 20% in December, not to mention double the volumes imported a year ago. Bacon imports in January were 27,000 tonnes, compared to 9,500 tonnes a year ago and 17,500 tonnes in December.

Market trends like these spell trouble for UK pig producers.

Since writing this piece in the spring, the AHDB has reported a recovery in market figures to nearer normal levels. However, this does not mean that pig farmers are any better off than they were earlier in the year.

Nose before yes, says Morrisons

Yorkshire-based supermarket Morrisons is going to give up using best-before dates on a lot of its liquid milk lines and is telling customers to sniff the milk as they take it out of the fridge and make their own minds up as to whether or not it is fit to drink. The story appeared on the BBC, which added that milk is one of the most heavily wasted foodstuffs, with 490 million pints being dumped every year, 85 million of which is slung out because it had passed its best-before date. Properly managed refrigeration can keep milk wholesome beyond this time, which is a suggestion not a statement of fact.

What makes an English breakfast?

The first shipment of Danish bacon arrived in October 1847. Through the nineteenth century, Denmark used to export wheat to Britain, but North America’s railway network reached the east coast in the 1840s and generated a tidal wave of cheap grain across Europe. Like the rest of its European neighbours, Denmark was unable to compete with transatlantic prices and turned instead to converting American grain into eggs, dairy products and bacon. At this time, the whey left over from cheesemaking was fed to pigs, who can put on 100 grams a day to their body weight.

Throughout the nineteenth century, Danish agriculture underwent a transformation in which livestock cooperatives flourished, especially those raising pigs. In 1887, Germany banned imports of Danish pigs and bacon, which pushed the cooperatives to increase the volumes of bacon shipped to the UK. It is worth remembering that without universal refrigeration, pigmeat had to travel as salt pork or bacon.