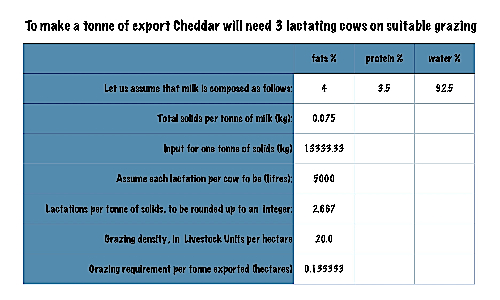

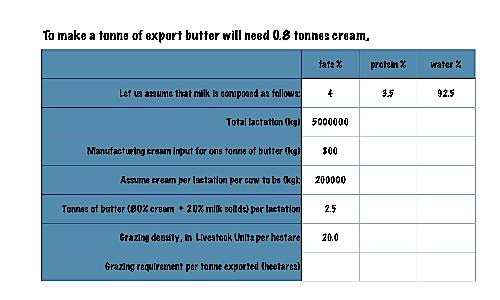

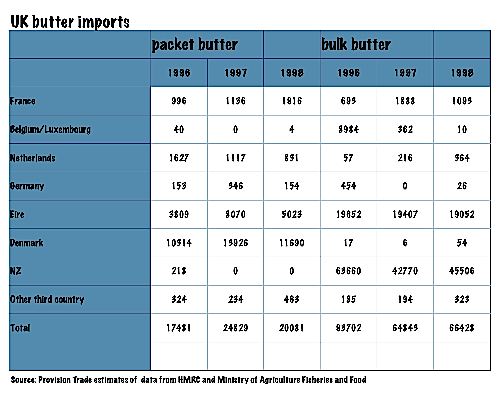

A cow producing 5000 litres of milk in a lactation (a lot by the standards of the 1990s) would give enough cream for two and a half tonnes of butter. Converting the remaining output into skim milk powder (SMP) would add a further couple of tonnes of powdered milk to the final output. There are other ways of splitting up milk fractions, some of them with limited use and application. Some standard variables appear in the first table, while the second outlines UK butter import tonnages for packet butter (retail product) and bulk butter for 1996-8, when the Common Agricultural policy was in full swing.

Taking the 1998 total packet butter imports total of just over 20,000 tonnes and when the total is divided by 2.5 (tonnes per lactation) it becomes clear that you will need at least 8,000 lactations — or lactating cows — to generate this tonnage. Bulk butter imports for that year topped 66,000 tonnes, needing a further 24,000 cows. Figures on this scale pose two serious questions.

First, is the UK economy capable of generating sufficient demand to increase domestic production by a comparable tonnage? Second, where would the UK accommodate an additional 30,000 dairy cows and the same number of calves that would trigger the necessary lactations? The chances are that the UK economy is not vigorous enough to generate investments in domestic production on that sort of scale. It is equally probable that the UK landscape would not absorb thousands of additional cattle and their calves.

The attraction of imported stock such as bulk butter is that it can be diverted into seasonal products like mince pies, which are planned into shifts after Easter and stored in a freezer until needed in the run-up to Christmas. Energy prices have made this pattern uneconomic this year, but it was a successful venture in previous years.

Butter comprises 80% cream and is transported in a refrigerated system. If there is no refrigeration, butter can be clarified. The process removes the water and heat sensitive protein, turning it into ghee. This can be kept in hot climates at ambient temperatures.