The biggest challenge that faces traders of all descriptions in arriving at a reliable price structure is the speed at which food products can change. Some animal products undergo a series of changes from farmgate to end user, others barely change at all. Some foods deteriorate very fast, while others are stable; add to this processes such as grading and the scope for differentiation can spiral out of control. For a comparison to be usable, the items need a number of similarities, bearing in mind that not all users will have the same interests. At the risk of keeping alive a business myth, there were some retailers who chose to take a cut in their margins rather than push up prices. Some individual members of of the Linlithgow committee would have been very well informed about specific markets and sector, but less inclined perhaps to share.

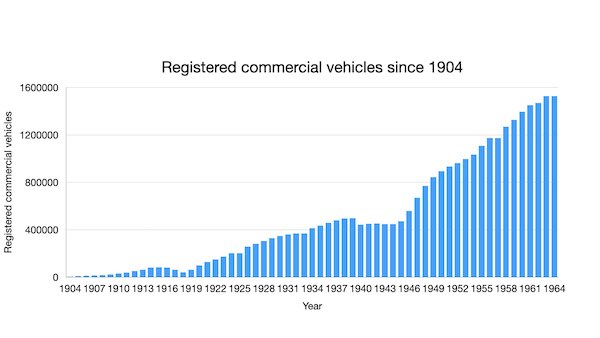

The stability and predictability of sectors such as cereal crops, milling and baking followed a pattern of incremental development. The step from wholesale trade to retailing, however, marks a sea change, reflecting the finer detail in retail distribution and home delivery costs. Investing in automotive resources ran deep in the bedrock of the economy of the day and was not going to be neither quick nor cheap.

The constant chivvying for market data was neither focussed for the most part nor available in the sort of unambiguous form that would have helped lay readers to learn more about the free market edifice. For instance, try explaining day-to-day shifts in retail pricing, arising from wholesale price changes that operate on a different basis. Even the denominations of coinage had an impact in the pricing of the retail world.

The ministry dug its heels in and refused to make a rod for its own back. The public should not be left to be baboozled by the high power antics of economists. How could such experts in their individual fields be left to explain the rise in mutton prices was a consequence of higher wool prices? After all, sheep are not killed for their wool.

Spare a thought for Tex, a grizzly bear with form for breaking, entering and… eating. It should come as no surprise that between fishing trips, Tex likes urban environments. Something to do with easy pickings and creature comforts, no doubt. Apparently, the Canadian state has teams of animal experts who monitor delinquent grizzlies, inter alia. Some weeks ago, Tex took a high-risk

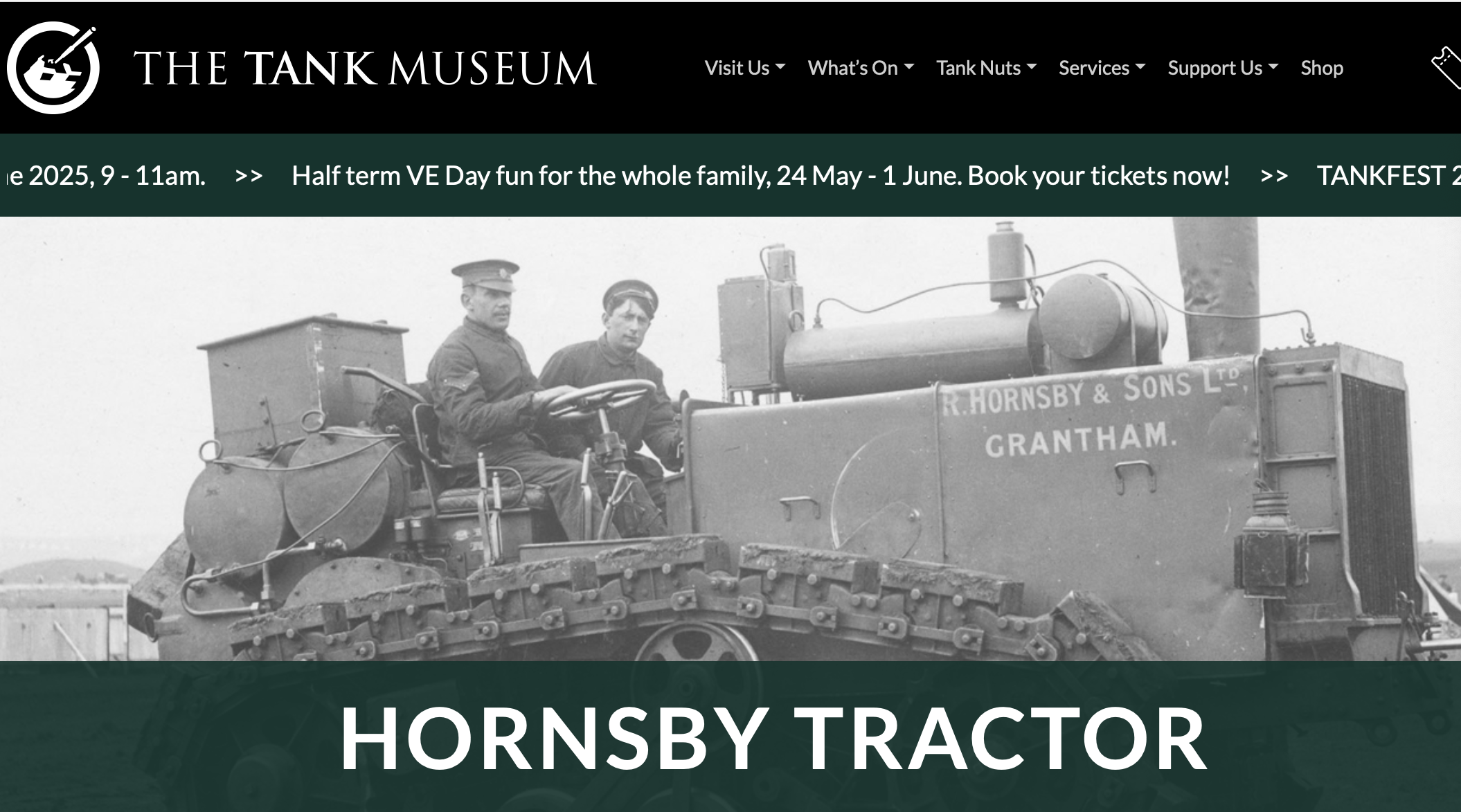

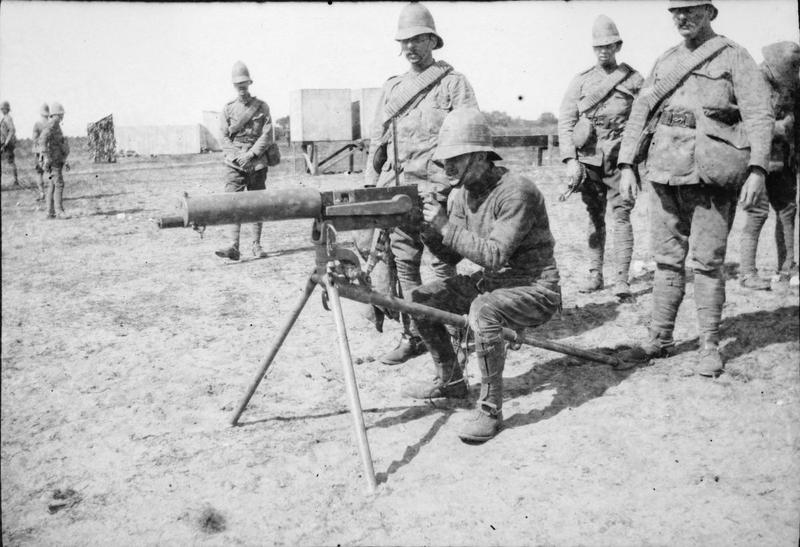

Spare a thought for Tex, a grizzly bear with form for breaking, entering and… eating. It should come as no surprise that between fishing trips, Tex likes urban environments. Something to do with easy pickings and creature comforts, no doubt. Apparently, the Canadian state has teams of animal experts who monitor delinquent grizzlies, inter alia. Some weeks ago, Tex took a high-risk  Urban Food Chains has chipped away at a series of posts on the introduction of heavy machine guns which carried out a mechanised cull of thousands of working horses and pack animals. Intentionally or otherwise, the result was to clear the way for commercial motors of different sorts on British roads. Rule of thumb loading practices for draft animal at the time would have been about 20% bodyweight. Given that the working life of a horse can be up to 20 years and you have to spend four years feeding and training them before putting them to work, there was no point in sending fit young horses to battlefields to die within weeks of arrival having realised only 0.00520833 recurring of their potential work capacity (one month, a notional average) had they lived to work for 16 years, or close on 200 months.

Urban Food Chains has chipped away at a series of posts on the introduction of heavy machine guns which carried out a mechanised cull of thousands of working horses and pack animals. Intentionally or otherwise, the result was to clear the way for commercial motors of different sorts on British roads. Rule of thumb loading practices for draft animal at the time would have been about 20% bodyweight. Given that the working life of a horse can be up to 20 years and you have to spend four years feeding and training them before putting them to work, there was no point in sending fit young horses to battlefields to die within weeks of arrival having realised only 0.00520833 recurring of their potential work capacity (one month, a notional average) had they lived to work for 16 years, or close on 200 months.

Recently, there has been a slew of posts about horses on this blog with more discussion than explanation. Some of you may remember that the narrative line in this blog goes back to prehistory, when humanity was sheltering from an ice age climate alongside a number of species that we now work with very closely, such as horses and cows, not forgetting companion creatures, such as cats and dogs. During the ice ages, we didn’t get to choose a place to shelter, we just piled in and got by as best we could. At one end of the spectrum, living in one place by choice can be called domestication, at the other end it can be purgatory. Everybody brings something different to the party: night vision; accurate identification of wild fungi; encyclopaedic knowledge of next year’s runners in the Grand National; whatever. For centuries, the norm has been anthropocentric and horses are expected to fit in with some pretty unimaginative stereotypes. An animal that goes down the gallops most days with Grand National runners would form a view of its rivals fast enough, but it will take humans an eternity to tune into this idea, let alone think of asking for an explanation. Horses just get it. They can see a problem when it’s still just a dot on the horizon.

Recently, there has been a slew of posts about horses on this blog with more discussion than explanation. Some of you may remember that the narrative line in this blog goes back to prehistory, when humanity was sheltering from an ice age climate alongside a number of species that we now work with very closely, such as horses and cows, not forgetting companion creatures, such as cats and dogs. During the ice ages, we didn’t get to choose a place to shelter, we just piled in and got by as best we could. At one end of the spectrum, living in one place by choice can be called domestication, at the other end it can be purgatory. Everybody brings something different to the party: night vision; accurate identification of wild fungi; encyclopaedic knowledge of next year’s runners in the Grand National; whatever. For centuries, the norm has been anthropocentric and horses are expected to fit in with some pretty unimaginative stereotypes. An animal that goes down the gallops most days with Grand National runners would form a view of its rivals fast enough, but it will take humans an eternity to tune into this idea, let alone think of asking for an explanation. Horses just get it. They can see a problem when it’s still just a dot on the horizon.