For years now we have made doomsday predictions of what would happen when the earth started to heat up in earnest. Covering two thirds of the globe’s surface, the oceans are an obvious places to start looking for the intense and complex lifestyles of people like the Baujau, who have built a way of life in pockets of sheltered coastline. The groups live by the sea in the Phillipines, Malaysia and Indonesia. Perched atop marginal menisci of tidal sand, their houses are in constant need of repair. The fisher folk take in huge lungfuls of air and freedive down to the reef, 20 metres below. Dives to 12 or 15 metres are common, compared to 5 metres for an active swimmer. A BBC team filmed them in action in 2020, ensuring that their way of life would be preserved for posterity. Women dive as routinely as the men, who will catch 15 kg or more in a morning’s fishing. One of the strongest freedivers filmed by the BBC used to be out at sea by 4 in the morning, and back on the shore around midday, with catches of about 15 kg. Having evolved bigger spleens, the Bajau divers can hold their breath for longer. Fisher woman Ima Baineng explains that the Bajau inherited their knowledge of fishing and the underwater world around them from their ancestors. She started diving at the age of four and went to sea with her father regularly from a very young age. “The corals are where the fish breed and if they suffer any damage, there won’t be any fish left,” she says.

The Bajau are completely committed to preserving the sea, which is hardly surprising since it keeps them fed. If, or when, life in the oceans fades away, the Bajau will be the first group to feel the consequences. For now, there has not yet been a complete breakdown in the fishing, but there are growing numbers of damaged reefs and the Bajau lack technology to meet the potential threats head on. They are are politically active across the region: “From our ancestors to our great grandchildren we protect the coral,” says Mandor M Tembang. The Bajau efforts to preserve coral should be adopted as a standard for international conservation projects, argues Coral Reef Ambassador Muh Yakub, making the point that while Bajau coral management practice still works and is sustainable, there are good reasons for it to be supported.

Tuna are fearsome hunters and eat whatever the ocean currents bring. In previous years, the composition of plankton around the world has been relatively stable. As the sea warms up, the effects on the food supply become clearer. The ocean can carry more nutrients, if the opportunity arises. Riding the wave are species that were once considered as lunch. Turning briefly to tuna, they were once major predators, preventing coastlines getting piled high with trailer loads of beached jellyfish. Now look closely at a fish that has been raised in a fish farm — and preferably with a microscope or a magnifying glass. You’ll need a reference picture too, just confirm that you know what you’re looking at.

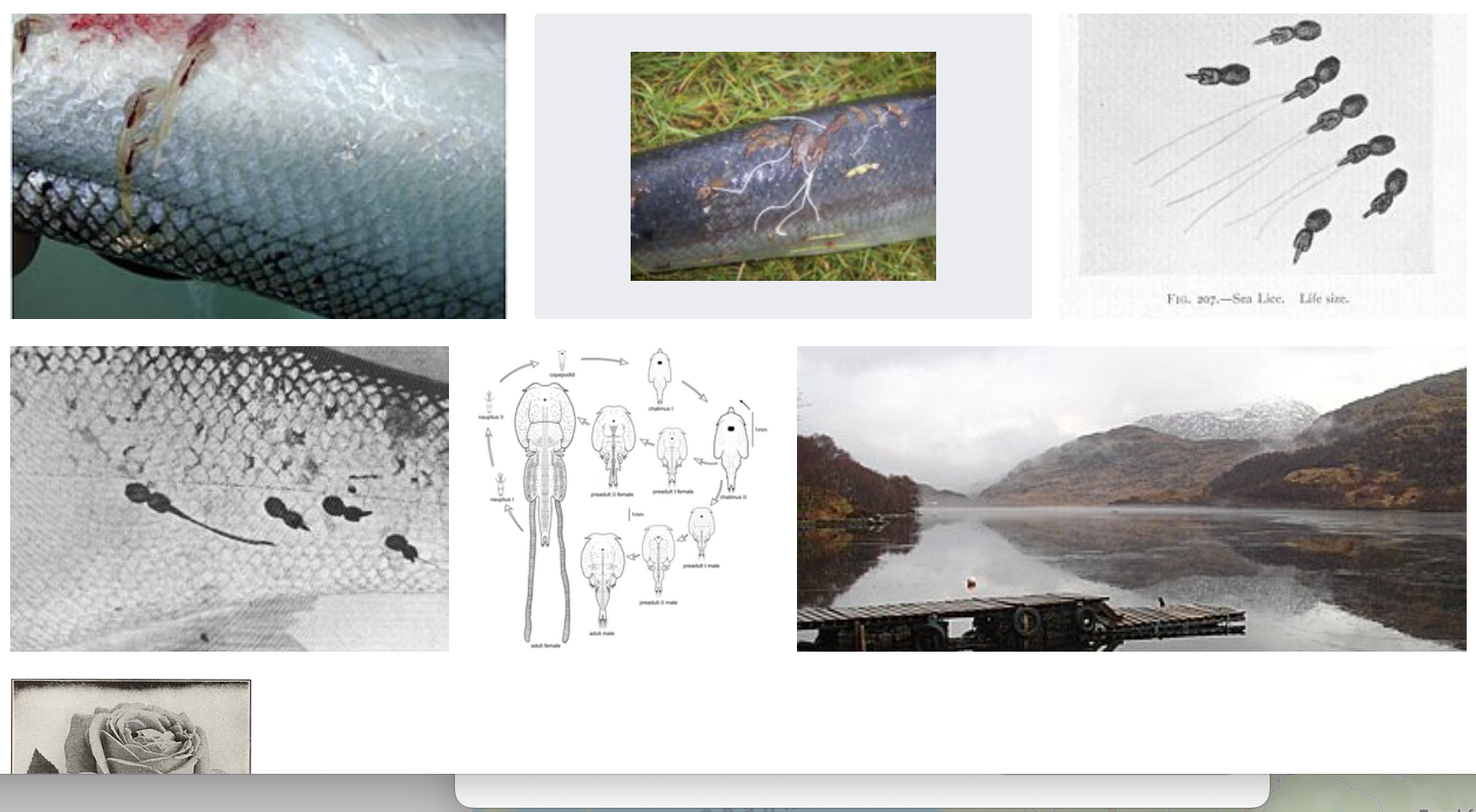

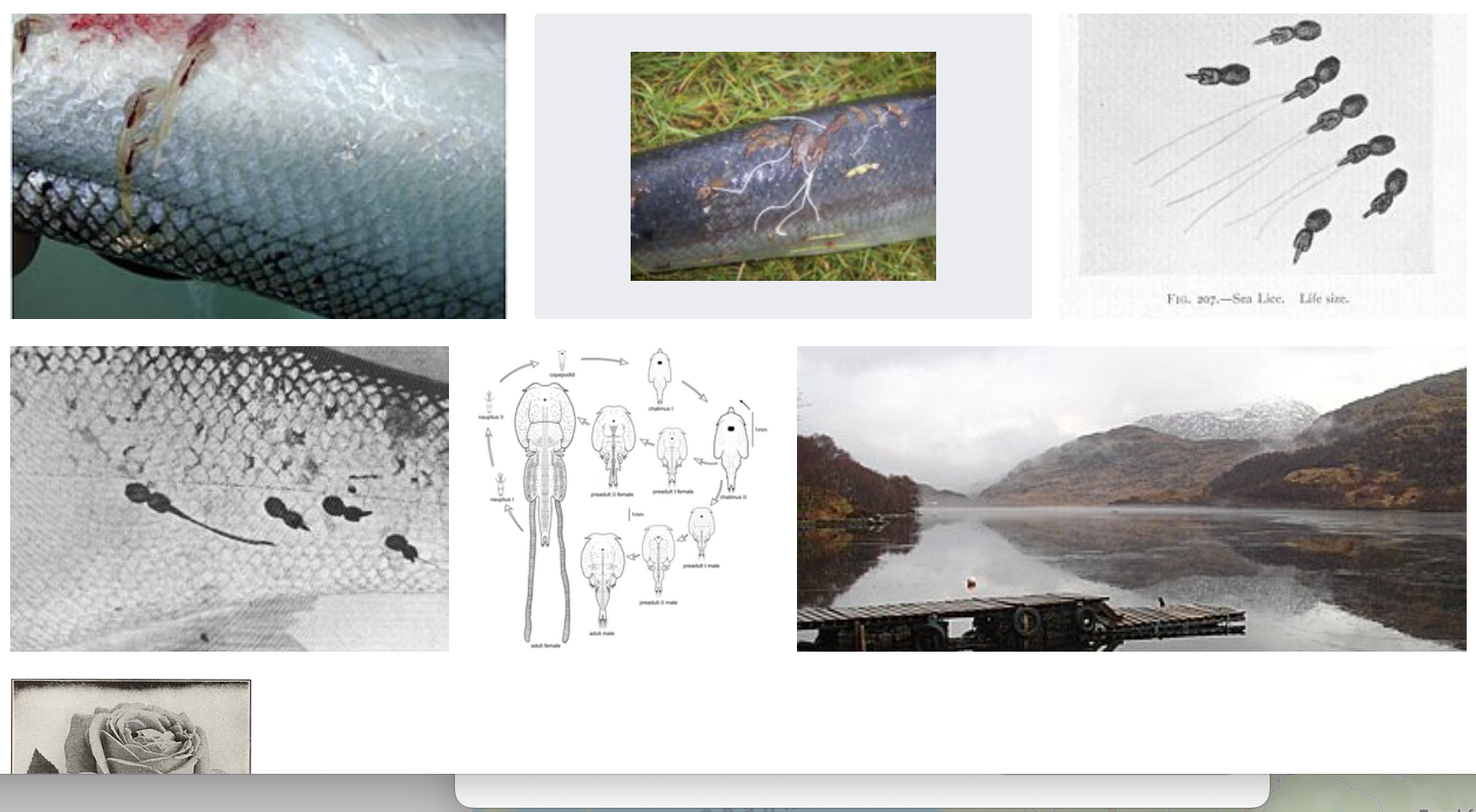

Start off on Wikimedia Commons to get an idea of what is available. Enter sea lice salmon in the search box and sit back, popcorn at the ready. I have just tried this: blink and you’ll miss it! To save time, here’s a screengrab, showing three infested fish. In the top lefthand corner is a salmon (photographed in 2013); top centre an Atlantic farmed salmon and on the lefthand side again, an image of a brown trout retrieved from the publication of a book in 1910. Another sea lice picture, from the same publication occupies the top right hand corner, a 2020 diagram from Bergen University is centre left, while the 2010 picture of Loch Eilt was part of a photographic survey of the UK. How I came to snag a 1921 book cover on growing roses is a total mystery.

Now I’m not convinced that this even a drop in the ocean of general knowledge and I would say that there is an elephant in the room, getting in the way of some fairly basic facts that are uncomfortable for some folk.

Let’s start with sea lice, otherwise known as jellyfish larva. They used to have much lower survival rates in previous centuries, needing to embed themselves in the skin of an active fish soon after hatching. In the open waters of the world’s oceans, sea lice are way down the food chain, scattered far and wide. But a fish farm is an oasis of opportunity for countless creatures, even such a random life form as a jellyfish. Hold that thought for a moment and ask yourself “Does a jellyfish ever decide anything?” No sooner have we posed the question than we have a ready answer: no way. It’s quicker than asking a jellyfish, for sure. They are simply not great communicators and it’s not personal: it’s a species thing.

Back at the fish farm, arrivng sea lice are greeted by the sight of more fish flanks than they could ever hope to get their teeth into. Beneath some of the fish cages there are piles of uneaten feedstock, that literally slipped through the net, not to mention wild fish cleaning up on the leftovers from above. By the time all this has been redistributed, another batch of tiny sea lice have hitched rides on both wild and captive fish. Life goes on.

There is something of a paradox in the way that creatures which are totally incapable of navigating in any sense of the word, should end up in such well-adapted feeding stations. The correlation between the extensive growth of fish farming and the resulting scourge for wild and captive populations is too well established to be talked down. Around the world, as well as exemplary sites, there are locations where ocean drifters have been carried to the kind of habitats that once upon a time, a species could only dream about. In the meantime, reputable fish processors reassure their customers that their hands are clean. Only top grade fish enter their premises and none but the finest salmon is handled on their lines.

Alongside the growth in fish farming has been the development of a mass market for smoked salmon. Conveniently for some fish farmers, it is possible to recover some marketable product even if the skin is less than perfect. Not that anyone would ever do such thing, you understand.

Drifters and evolution

Earlier in this blog I touched very briefly on the domestication of species that we now regard as part of the family, so to speak. The timespan for this process is counted in millennia, hundreds of generations. Is evolution a process that can be directed or driven? Or is it a developmental drift? Is this even a topic worth investigating? Share your thoughts in a comment and give me a break from folk with cryptic email addresses and obscure sales messages.

More follows later if there is a demand for it…

This could not come too soon, as inter-war businesses set about restoring their delivery systems. When trying to track the development of value in the pricing of bread and bakery goods, the editor of Industrial Peace, Major W Melville, conceded that the public grasp of the price structure was “little understood”. The only accessible estimates came from the Linlithgow Report and started outside bakeries with the purchase of sacks of flour. From the plains of north America, the vast expanses of Australia, to the more modest arable holdings of England, Linlithgow collects the entire growing stage of breadmaking flour into a single undifferentiated lump.

This could not come too soon, as inter-war businesses set about restoring their delivery systems. When trying to track the development of value in the pricing of bread and bakery goods, the editor of Industrial Peace, Major W Melville, conceded that the public grasp of the price structure was “little understood”. The only accessible estimates came from the Linlithgow Report and started outside bakeries with the purchase of sacks of flour. From the plains of north America, the vast expanses of Australia, to the more modest arable holdings of England, Linlithgow collects the entire growing stage of breadmaking flour into a single undifferentiated lump. The disadvantages of average returns are there for all to see. Melville put it like this: “No evidence offered in respect of price structure of flour. My inquiry begins at the point at which the baker buys his flour from the miller.” The opening price of breadmaking flour in January 1923 was 42 shillings and a penny. There is no indication of whether this should be taken as an “asking” price or a “taking” price, as given in a trade paper, meaning that flat pricing goes out of the window, speeded on its way by discounts applied at strategic order volumes. The figures discussed in the Linlithgow report were fixed during a time when flour prices were starting to fall, leaving a number of question marks over the validity of 42 shillings and a penny as a credible price for a sack of flour at this time.

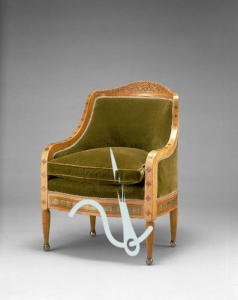

The disadvantages of average returns are there for all to see. Melville put it like this: “No evidence offered in respect of price structure of flour. My inquiry begins at the point at which the baker buys his flour from the miller.” The opening price of breadmaking flour in January 1923 was 42 shillings and a penny. There is no indication of whether this should be taken as an “asking” price or a “taking” price, as given in a trade paper, meaning that flat pricing goes out of the window, speeded on its way by discounts applied at strategic order volumes. The figures discussed in the Linlithgow report were fixed during a time when flour prices were starting to fall, leaving a number of question marks over the validity of 42 shillings and a penny as a credible price for a sack of flour at this time. The opening pages of the Charié report (vol 1, p17) carries a parallel message, likening a distortion of competition to a pin left behind in an armchair. No matter how well-appointed the chair, a single pin can render it unuseable. (montage: Urban Food Chains)

The opening pages of the Charié report (vol 1, p17) carries a parallel message, likening a distortion of competition to a pin left behind in an armchair. No matter how well-appointed the chair, a single pin can render it unuseable. (montage: Urban Food Chains)