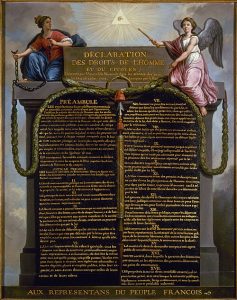

The opening weeks of the French revolution saw the drafting of a declaration establishing the existence of human rights and what each person was obliged to do to protect the same rights and privileges for their fellow citizens. These boundaries can only be determined by law. As we shall see later, there was no question of extending such protection to animals, let alone the natural world or even the planet. This anthropocentric oversight is something we are still paying for and is unlikely to be resolved in an equitable fashion.

The opening weeks of the French revolution saw the drafting of a declaration establishing the existence of human rights and what each person was obliged to do to protect the same rights and privileges for their fellow citizens. These boundaries can only be determined by law. As we shall see later, there was no question of extending such protection to animals, let alone the natural world or even the planet. This anthropocentric oversight is something we are still paying for and is unlikely to be resolved in an equitable fashion.

We need to start somewhere and there is every sign that even exemplary revolutionaries will struggle with the idealistic aims of human rights: the planet comes off second best in the face of such the supposedly universal rights, as do flora and fauna the length and breadth of the planet. Having claimed the lion’s share of the world’s natural resources, the human revolutionary elite turned its attention to making a set of laws to withhold its new-found privileges from those who could possibly represent a challenge to future generations of global power brokers. The irony of this paradox is a heavy burden that is shared with nature in every corner of the globe: we have already seen some of the consequences in our atmosphere, our ocean depths and our chances of survival, but this is only this is only the beginning.