Having covered a blank canvas with lengthy discussions of horses’ roles in the transport of goods (click on a “horse” badge for the full list), the moment has arrived to resolve any lingering doubts. Registrations of commercial vehicles on British roads grew steadily in the 1920s: the figures used in this table are all civilian, there are no military registrations to factor in. 0 At the start of the first world war, the British government commissioned regular orders with about half a dozen automotive manufacturers equipped to fulfill wartime orders. During the hostilities, these firms built 20,000 vehicles for the military – mostly lorry chassis ready for adaptation once their role had been allocated. The government disposed of a further 6,000 vehicles that were either no longer required or beyond repair.

The only army horses ever to return to the UK were those belonging to officers, some 65,000 in all, out of a total of close on a million. There was very little reliable data on the UK’s horse population at this time. The country had been a long term importer of horses since the mid-nineteenth century. There were groups of draft horses traded by specialist breeders, who saw to it that strong lines of Shire horses, Suffolk Punches and Percherons were kept available for companies that needed to patch a gap in a team, or other specific need.

The British army commandeered as many horses as it could lay its hands on. The entire industrial world was short of mules and horses during the 1920s. It was the growing reliability of automotive products that helped some to turn the corner. There was a persistent chafing between England’s lorry drivers and coachmen who were still in a job. Knowing that the brakes on lorries were often barely fit for purpose, coachmen would wind up lorry drivers while loading their vehicles and persuade them to increase their load to a point where the vehicle was a danger to other traffic.

Town-dwelling horses were kept in grouped stables, or mews, usually bearing the name of the street they served. The equine diets were the standard fare of working horses of the day: hay, oats and roughage, washed down with water at intervals. Horses were the prerogative of the very rich or tradesmen who could cover their outgoings from their business. Agricultural businesses occupied the middle ground in this polarised rule of thumb scenario. The more successful ones worked with established lines of Percherons, Cobs or Shires, often breeding their own draft animals and systematically avoiding the saddle horse fraternity.

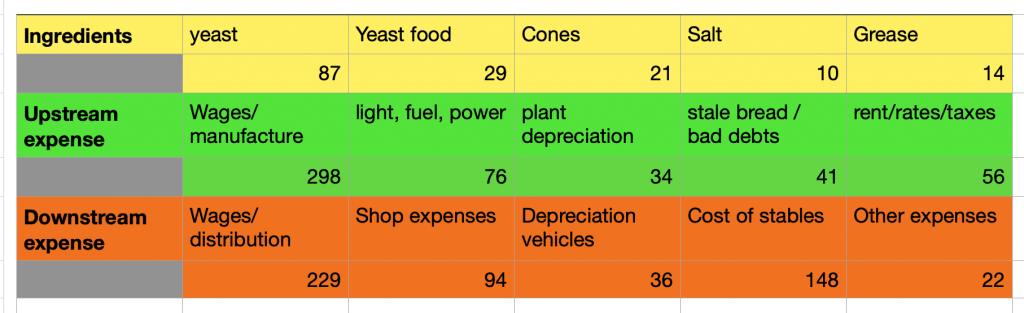

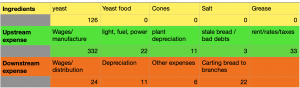

Town-dwelling horses were kept in grouped stables, or mews, usually bearing the name of the street they served. The equine diets were the standard fare of working horses of the day: hay, oats and roughage, washed down with water at intervals. Horses were the prerogative of the very rich or tradesmen who could cover their outgoings from their business. Agricultural businesses occupied the middle ground in this polarised rule of thumb scenario. The more successful ones worked with established lines of Percherons, Cobs or Shires, often breeding their own draft animals and systematically avoiding the saddle horse fraternity. The Linlithgow committee provided four business snapshots based on live data (1923 figures..) to illustrate how the sector operated. There is no way of telling how much m, but the ones they published cast some light on the baking sector. Only theWar Office refused to share any data. The most detailed is based on figures from the National Association of Master Bakers’ and a number of local associations. The Industrial Co-operative group gave a terse rendering of the Co-op’s pricing structure, which differs in smalll but significant ways from retail rivals. Third is a glimpse of the War Office bakery, in Aldershot. It went to extraordinary lengths to say nothing. For the time being, I cannot locate where Butler Brothers traded, but the firm operated a number of branches from a central bakery.

The Linlithgow committee provided four business snapshots based on live data (1923 figures..) to illustrate how the sector operated. There is no way of telling how much m, but the ones they published cast some light on the baking sector. Only theWar Office refused to share any data. The most detailed is based on figures from the National Association of Master Bakers’ and a number of local associations. The Industrial Co-operative group gave a terse rendering of the Co-op’s pricing structure, which differs in smalll but significant ways from retail rivals. Third is a glimpse of the War Office bakery, in Aldershot. It went to extraordinary lengths to say nothing. For the time being, I cannot locate where Butler Brothers traded, but the firm operated a number of branches from a central bakery.

As human populations settled, the first quality they lost was a deep awareness of a wider world beyond their existence. By leaving the land and settling in cities, humanity extinguished any remaining spark of interest in the outside world. This is just one of our nemeses emerging from the shadows. Others will catch us out sooner, but they lack the central importance of a planetary view of the natural world. Writing in Against the Grain, James C Scott reminds us that without the millennia during which prehistoric populations domesticated crops and livestock there would never have been agrarian city states. He also argues that such an important process need not be a linear progression, but that during those years human populations would have probably have lived by more than one activity, the exact combination of which would have changed with the prevailing conditions. Life in prehistory was difficult enough, without trying to stick to a linear progression from nomad to city dweller.

As human populations settled, the first quality they lost was a deep awareness of a wider world beyond their existence. By leaving the land and settling in cities, humanity extinguished any remaining spark of interest in the outside world. This is just one of our nemeses emerging from the shadows. Others will catch us out sooner, but they lack the central importance of a planetary view of the natural world. Writing in Against the Grain, James C Scott reminds us that without the millennia during which prehistoric populations domesticated crops and livestock there would never have been agrarian city states. He also argues that such an important process need not be a linear progression, but that during those years human populations would have probably have lived by more than one activity, the exact combination of which would have changed with the prevailing conditions. Life in prehistory was difficult enough, without trying to stick to a linear progression from nomad to city dweller.