Television advertisements get a seasonal boost over Christmas, many of them going off at a tangent to promote lifestyle changes. In the process, they can lose focus and clarity. This year’s Intermarché two and a half minute spot is a case in point, as you will see when you click the link above and run it. The animation is flawless, the soundtrack is bright and the subtitles are timed to perfection. The storyline should be as clear as day, or at least as good as the component parts. In this case, a family Christmas lunch scene dissolves into an insoluble conflict between a wolf’s longing for friends and the creature’s assumed carniverous background. To be sure, you can’t have friends and eat them (the reference to cakeism is deliberate), but you need something a bit more substantial than the “mother carries child off to bed” ending. If the ending rounded off a strong storyline, one might forgive the lingering doubts that follow the final screen. But with an understated narrative, the story fails to inspire, inform, or instruct. It has no clear statement to offer, nor lessons to learn. Which is a shame, given the high creative standards of the agency.

Pictures worth a thousand words

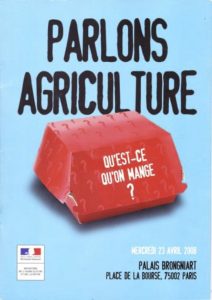

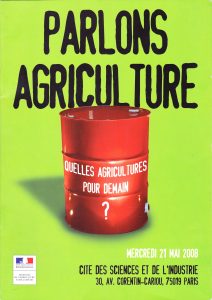

On April 23, 2008, Michel Barnier greeted hundreds of French citizens in Paris, who were disturbed by the farm minister’s use of a contentious image to promote a series of conferences about food. “We don’t live on burgers or fast food,” one lady grumbled, staring at a picture of a discarded burger box bearing the words “Qu’est-ce qu’on mange ?” (“what are we eating?”) Collectively, the conferences were promoted under the title “Parlons agriculture” – ‘let’s talk about agriculture’. The graphics are challenging, particularly for rural populations: as well as the burger box image you can see on this page, elsewhere in the posters and conference literature, there is a battered steel barrel that has not just seen better times, but is clearly toxic.

Starting with the blue booklet on this page, we will unpack the arguments and economics that were shaping agriculture in 2008. Here are the opening words from the minister: “Current events have just reminded us, with terrible consequences, that the world has yet to get rid of the scourge of famine. Egypt, Morocco, Indonesia, Cameroon, Mexico, Bolivia, every continent on the planet is seeing a resurgence of food riots, which harden men’s resolve and leave behind the smouldering wreckage of civilisation. History is being wrapped up in front of us as the world’s raw material prices rise in brutal leaps and bounds, food prices are soaring, traders all over the world are panicking. Rice, a basic food for half the world’s population was at the heart of this. Prices had risen by 54% since January (he was speaking in April) and major exporters were holding back their export tonnages. Today, three billion people live on less than two dollars a day, and the spectre of hardship hangs over them.”

Nearer to home “…hunger has been avoided for a long time, we think that shortages have become a thing of the past and there is an illusion of food security.” Look again and you will recall “mad cow disease”, alongside avian flu, arising from instances where feeding same-species animal remains have put human health in danger.

“In these times of great doubt, we need to bring together those who produce and those who consume, we need to end the mistrust between two worlds that have stopped talking to each other.”

Nowadays, [2008] …”wherever we live, a big question hangs over the new century: how do we feed humanity to ensure health and sustainability? Barnier argues that we can no longer afford to live in ignorance of past mistakes, guzzling saturated fats and rich foods can no longer be indulged. This is the underlying purpose of the conference: we need to share and exchange resources; weave a dialogue of a sort that has never been seen before; making it possible for agriculture to rejoin the rest of the world.

This morning (23-NOV-2025) I reposted a call to action made by Morgan, a radical peasant farmer. Speaking to camera, she calls on President Macron to head up a pan-European campaign to stop fruit growers being put out of business by cheap imports from Latin America. France has a strong enough voice to make itself heard on the international scene, Morgan argues. France should stop dreaming of its past glories and wake up to a very real threat, she warns.

Talk about agriculture..(2)

Here’s a challenge; how many agriculture ministers would cheerfully stake their political careers on the agressive tone of the visual below? Subtle as a flying brick, this artwork got right up the noses of the farming unions they were targeting. There can be nothing worse than projecting a goody two shoes image of your industry only to see the minister’s team spoil the effect.

French farming unions milked a government department that they thought they could call their own. For years, the FNSEA posted teams of so-called advisors in the corridors of rue de Varenne, who would be consulted on all manner of policy matters, trivial or otherwise. Fast food ingredients do not automatically earn thick margins in a competitive sector: even economists need to be realistic occasionally. In the middle of multiple crises with local, regional and national consequences, seemingly overnight we had a food crisis. Sociologist Claude Fischler, research director at CNRS, cautions against considering a collection of local responses to specific, localised problems will somehow add up to ways of working that will add up to a regional or national strategy that will work straight out of the box. In particular, there is an ever-present push-pull tension between planning for food security, (making sure that there is food on sale) including, but not exclusively, supermarkets and other distribution models. The rich world which was once home to eaters is now populated by consumers, with all the implications of added-value strategies. Consumers transfer their disposable income to products increasingly heavily-processed products, thus spending more on food and transferring market power to an ever smaller group of brand owners. As such, they become closed off to the outside world, in an increasingly bitter war of words to justify their positions, if only in their eyes. Food manufacturers focussing on sales targets and profit margins will drift out of markets in the hungry world, widening the gaps between consumers and ever greater numbers of starving populations who are constantly hungry. To say such things are “nobody’s fault” would be disingenuous but is often used to dissipate any blame implied.

French farming unions milked a government department that they thought they could call their own. For years, the FNSEA posted teams of so-called advisors in the corridors of rue de Varenne, who would be consulted on all manner of policy matters, trivial or otherwise. Fast food ingredients do not automatically earn thick margins in a competitive sector: even economists need to be realistic occasionally. In the middle of multiple crises with local, regional and national consequences, seemingly overnight we had a food crisis. Sociologist Claude Fischler, research director at CNRS, cautions against considering a collection of local responses to specific, localised problems will somehow add up to ways of working that will add up to a regional or national strategy that will work straight out of the box. In particular, there is an ever-present push-pull tension between planning for food security, (making sure that there is food on sale) including, but not exclusively, supermarkets and other distribution models. The rich world which was once home to eaters is now populated by consumers, with all the implications of added-value strategies. Consumers transfer their disposable income to products increasingly heavily-processed products, thus spending more on food and transferring market power to an ever smaller group of brand owners. As such, they become closed off to the outside world, in an increasingly bitter war of words to justify their positions, if only in their eyes. Food manufacturers focussing on sales targets and profit margins will drift out of markets in the hungry world, widening the gaps between consumers and ever greater numbers of starving populations who are constantly hungry. To say such things are “nobody’s fault” would be disingenuous but is often used to dissipate any blame implied.

A more urgent question is whether or not poor countries should be assisted to stimulate higher productivity among their fellow citizens, with an ever-greater risk of system failure in technology that will stop working sooner or later. Capital-intensive systems have less to offer traditional peasants with lower capital exposure, they are also more likely to survive extended drought or unforeseeable weather conditions (climate change).

Let’s talk agriculture!

The Barnier oil barrel image, reminding everyone that modern agriculture has an environmental cost.

In June 2008, Michel Barnier left rue de Varenne after two years as France’s farm minister. He was outwardly at peace with the world, after two years spent steadfastly denying that he had any serious differences of opinion with President Nicolas Sarkozy. This was not altogether convincing, since Sarkozy was prone to talk up his chances of successful plans and policies long before they were anywhere near ready to be seen in public. Such stoicism in the face of a president that spoke first and thought later does not come easily, as the Americans are learning in 2025. Barnier was trained as an administrator, graduating from the École Supérieure de Commerce de Paris (ESCP) in 1972 .

This does not mean that he is a rug to be walked on: far from it. He won a number of internal battles without comment. Some of his victories were reversed by political opponents who went over the minister’s head and persuaded the President to see things their way. People such as Xavier Beulin, head of the FNSEA, had Sarkozy’s ear and seized any opportunity to put ideas into his head (click here). In Beulin’s case, it was personal: the farming unions had operated a system for sitting in on internal ministry meetings and generally making sure that the FNSEA view prevailed elsewhere in the ministry. If this sounds overstated, have a look at this post, describing the modus operandi. Barnier cleared the corridors of unwanted loiterers, by simply re-issuing security passes to ministry staff and setting higher security standards at rue de , Varenne. He also succeeded in raising the level of public debate around agriculture with a series of state-sponsored debates scheduled for 2008. There were two in Paris and a third in Brussels. There was no mistaking tone of the events, which challenged the FNSEA ‘s founding principles, namely to corner every centime of public funding for agriculture. A battered steel barrel, dominates one set of conference documents, with the question of the day in big white letters: “What kinds of agriculture(s) do we want for tomorrow?

Barnier sets the scene in the opening paragraph: “There can be no doubt that the outlook for the world has changed. The abundance of nature that we have unthinkingly squandered has now given way to a weak and fragile planet, in which resources are threatened. Today, we have the results of years of work from the scientific community. We can no longer ignore them.The age of widespread scarcity has begun.” Readers will be glad to learn that unless things turn nasty, I shall make these two conference documents available for as long as possible. I have no plans to offer a translation unless a significant number of people request one. There is no way I would put the documents through an AI system, the words are too carefully balanced to survive a bot’s blunt ignorance and I haven’t got the necessary time to make a useable translation.

There can be no discussion of how to set things back on track without an understanding of population dynamics. Barnier sketches it out like this: “The prodigious population explosion that marked the 20th century is set to continue until 2050, at least. It will impact the poor world, in the places where hunger is already rife and in urban areas, where eating habits at all levels of society have been messed up.” Up until now, Barnier argues, humanity has usually been able to patch things up with technical solutions. In 2008, there was a glimmer of recognition that the scale of the problem was greater than anyone imagined.

“Faced with rocketing food costs (in 2008), confronted by food riots, hampered by shortages of basic resources: the strategies which we used to think would solve the problem will do no such thing.

“We are faced with an equation, the like of which we have never seen before (still in 2008) (the French use “inédit” so much that it ceases to carry much weight) . “To deal with the problem, on the basis of current evidence we have to break with development models that will increase the consumption of finite resources. This is what makes the situation so urgent, since all the checks and balances that keep the planet in working order are threatened.”

MORE FOLLOWS LATER

When is a peasant not a peasant?

France’s national farmers’ federation, the FNSEA, is more like an advertising agency than a trade union. When marching in national demonstrations, they make a point of referring to themselves as ‘paysans’ (peasants), . Dare to call one of them a ‘peasant’ away from the television cameras and you’ll get a bunch of fives and a reminder that there is more to farming than spreading muck. While I was learning my way around government offices in Paris, I found myself being quizzed by a couple of burly agricultural types. I had just arrived at the agriculture ministry in rue de Varenne with an appointment to talk to the minister about the Common Agriculture Policy. These two weren’t as smartly dressed as the ministry staff, but were very interested in my business, only withdrawing when they spotted the minister’s chef de cabinet coming back. “Ouf, les syndicalistes, c’est pénible,” he groaned. “Lequel syndicat…?” “FNSEA.” The conversation moved to less thorny topics and I took a sheaf of papers from my briefcase. “…let’s show those to my advisers, shall we…?” the minister pleaded. There was a brief exchange of words at the office door, just enough to identify the pair I had met in the foyer minutes earlier. “…subvention? …fonds publiques…?” This was clearly a fishing trip. “C’est un thème d’interet tout public…” I started. “…donc le public va payer…” came the answer. Stripped of any wider context or or even interest, the topic pretty much curled up and died on the spot.

Who lost out in the revolution?

At the turn of the nineteenth century, Napoleon redrew the map of Europe. He suspended all the laws in France that preceded the revolution. He replaced them with a series of codes or simple, clear legal frameworks, giving men total power over women; removing any political power that religions may previously have wielded; defining the laws of things, such as property, along with the rules governing its transfer. The third section covers succession and contracts, listing valid forms of agreement. The code also defines obligations and contracts. It dumped a lot of hard-fought revolutionary principles, not least womens’ rights. It was not until well into the twentieth century that some of these were restored.

The Code de la Commerce established the principle that it should be illegal to sell at a loss. Article L 442-5 has been the object of extensive discussion and attempted modifications ever since, as people have looked for ways round it. When Sarkozy came to power in 2007 there was a determined effort to redraw the political landscape of the French economy. La loi de modernisation de l’économie (LME) was an administrative bulldozer, which slashed payment terms for invoices, setting a new ceiling at 60 days and easing planning requirements for small (less than 1,000 square metres) retail premises. In among the debris was the legislative wreckage of article 442-5.

The parliamentary passage of the LME was a baptism of fire for a novice parliamentarian at the time, Bruno Le Maire. His first major legislative task was a sea change for the economy. He also succeeded in making annual buying reviews for retailers and their suppliers a passage through purgatory by reversing the buying cycle. In previous years, suppliers would deliver goods through the year and meet at the start of the next year to discuss terms for the coming year. With a year’s worth of sales data to hand, suppliers were in a position to offer retailers end-of-year bonuses for specific listings and stay in business. Under Le Maire’s system, suppliers are expected to guarrantee a price for the coming 12 months, field demands for promotional stock and stay in business to do it all again the following year.

Links to further posts on this topic will appear at the foot of this page.

Burning question

Wildfires across huge areas of southern Europe mean even more bad news for olive oil and table olive packers. It is impossible to predict the full effect on this winter’s prices for olive oil or table olives, but there will be direct consequences. This is not a complete wipe-put story, since established olive trees with deep root systems can recover from fires, although this will take time. Young olive trees are more susceptible to fire damage.

The immediate impact will be on packers and blenders of olive oil, particularly in Italy: these skilled folk have a network of suppliers for very specific oils with relatively rare qualities. The suppliers of such rarities are spread over the continent, from Gibraltar and north Africa down to the middle east. The trading network is complex and known to a handful of olive oil blending experts.

In a year when the mainstream crop is already looking patchy and fraught, this will mean higher costs for the retailers. In the UK, the multiples are reluctant to let their double digit margins take a hit and will do their level best to make sure that suppliers carry the burden. The situation is, however, beyond horse trading. Bulk olive oil prices will be non-negotiable, where there is product to be had. Looking at the Mediterranean over the next few weeks, the following impacts can be expected. Industrial tomatoes for peeled plum tomato canning lines can be expected to be short, since crop irrigation is being used for firefighting. Chopped tomatoes, passata and tomato paste can be made from almost any variety of tomato and production is not limited to southern Italy. Table olives are under a shadow, with a high risk of localised damage: a lot of olives will have been burnt off the trees. Durum wheat, essential for pasta manufacture, may have escaped the worst of the heat waves, but export tonnages will probably be restricted.

For the latest information on the European forest fires, click here.

Footnote on the protagonists in Time Travel for Food

Leadership is something we all respond to and it takes many forms.

Take a figure from history, such as Napoleon Bonaparte. A product of the ruling elite of his day, Napoleon underwent officer training and was undaunted by meeting calls to define the working structure of a post revolutionary state from scratch. The Codes Civils (sometimes referred to as the Napoleonic Codes) were an object lesson in structuring the edifice of a state at the start of a post-royal era (https://urbanfoodchains.uk/forging-urban-food-chains/). Bonaparte had the outward signs of a civic visionary and expected to lead from the front.

Employing a completely different set of skills, Nicolas Appert perfected the system of sealing food into bottles or cans and cooking it so thoroughly that the product would keep indefinitely. Sometimes referred to eponymously as Appertisation, the process has been used with very few changes, for more than two hundred years. Appert predated fellow Frenchman Louis Pasteur by just over 60 years and would not have predicted the link between heat treatment and killing pathogens that Pasteur would make in years to come.(https://urbanfoodchains.uk/time-travel-for-food-2/)

There are grounds to suppose that the Appertisation process was known to food producers, but not widely practiced in the 1790s. In place of a theoretical explanation for the incontrovertable success of the process, Appert constantly ran tests on batches of food, using bottles and stoppers of all sorts of material: ceramic, glass and metal. As the years progressed, his confidence in the process grew, as he learnt what cooking times different foods needed in a water jacket of boiling water. Nicolas Appert had been raised by an inn keeper working in Chalons-sur-Saone and was a competent chef. His entire working life was focussed on feeding people and by the 1790s Appert was working as a confiseur in a Paris suburb.

A confiseur is someone who cooks off food, usually with boiling water, to make range of “confits” or foods almost cooked to a mush. Confiserie refers to boiled sugar confectionery, while confits are table-ready dishes which can be sweet or savoury and typically capped off with a layer of fat. The aim is to cook off seasonal gluts, although meat-based confits had short shelf lives, since the melted grease did not offer any real protection to the dish. This was the reason for Appert’s interest in sealing his wide-necked bottles, in a bid to extend shelf life. Appert successfully got reliable results, which is why Appertisation is referred to as “Time Travel For Food” on this website.

Appert plied his trade as a confiseur and wholesale grocery from a workshop in rue des Lombards. He was a member of the militant Section des Lombards, who mobilised at moments of crisis during the revolution in Paris. An active Jacobin, Nicolas and his wife Elisabeth supported the revolutionary cause in practical ways, such as holding planning meetings in the workshop.

As readers will learn in the short history of Nicolas Appert, the confiseur was pulled into the Jacobin Terreur, saved only by the fact that Robespierre was executed 36 hours before Appert was due to go to the scaffold. The Appert household survive the latter years of the revolution: Nicolas is awarded an “encouragement” of 12,000 gold coins by Napoleon. This comes with a requirement to publish a manual to Appertisation at his own expense. Appert remained politically active during his life and was elected mayor of Ivry-sur-Seine.

Appert also makes a trip to England in 1814, at the height of the Napoleonic wars. The reason for the trip was for after-sales support for an English engineer who had licenced the process for commercial exploitation. The technology transfer had been overseen by Pierre Durand, a Bordeaux wine merchant turned intellectual property agent. Durand’s leadership style was simply blunt and overbearing. He met his match, however, in Bryan Donkin, his English client.

A highly regarded engineer, Donkin had undertaken work for the Fourdrinier brothers, Henri and Seely, to make their purchase of a design for a papermaking machine work in a paper mill environment. As his French clients faced bankruptcy and Donkin still had a workshop to keep in production, there was a pause in proceedings during which Donkin tried to stake a claim on what is known today as the Fourdrinier papermaking machine. Resourceful as ever, Donkin contrived to settle the name of the machine on the brothers, but retained control over the crucial detail that allowed him to sell working papermaking machines in his own name. Since he installed almost 200 machines across Europe, one can suppose that he was commercially successful. It should be added that Donkin also patented the dip pen and a number of nib designs, which generated far greater sales than could be earned from selling a papermaking machine. This management style is close to opportunistic, but shows a high level of resourceful thinking. Bryan Donkin’s grandson, called Bryan after his grandfather, developed and patented the Donkin gas valve, which is more widely known than Donkin senior’s achievements.

Forging urban food chains

France in the closing years of the 18th century was in total chaos. The Terreur (terror) reached its height with the execution of the Jacobin leader Maximilien Robespierre in the summer of 1794. In the years that followed, the Consulate took control led by Napoleon Bonaparte. The young Napoleon set himself the task of clearing away all the old laws and the rag-bag collections of local regulations (“coutumes”). He replaced them with the “Code Civile” that set out the rules for a constitutional reset.

The code was secular and written in ordinary French. It detailed what was expected of citizens — considering men to be equal before the law, while assigning women the role of dowry-bearers, facilitating the transfer of property and assets between families. Because of the contractual importance of marriage, there were elaborate requirements to ensure that men were legitimate before they could be married. The husband owned his wife’s dowry, but not her paraphenalia.

The code also laid out commercial frameworks and set standards for product liability. For instance, artisans and craftsmen were required to give a ten-year guarantee on their work. When selling land, sellers were obliged to include the oxen teams and equipment needed to work the land. And those acquiring livestock with a farm were required to keep the animals exclusively on that farm, keeping the dung on the holding. It is worth remembering that rural France was heavily populated in those days, but over the coming century, this was about to change. The Code applied to both town and country, as well as to those on their travels. For example, innkeepers had a legally enforceable duty of care for their guests’ goods and chattels, which extended to those working on the premises, protecting them, too, from light-fingered interlopers.

The March 1804 version of the Code Civile had more than 1800 paragraphs and was the largest version to be put up for adoption. There were prolonged debates about all three circulated versions, each with different numbering and paragraph counts. Some of the articles in the Code Civile still apply to this day, often heavily modified. The administrative commitment to a document-based system put a greater priority on literacy. Deaf or visually challenged citizens who could read had protected access to the provisions of the code unlike non-readers who made their mark to sign off documents they could not read.

Packing them in

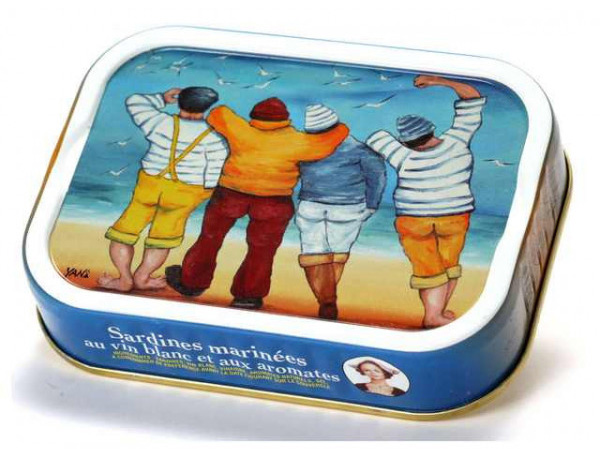

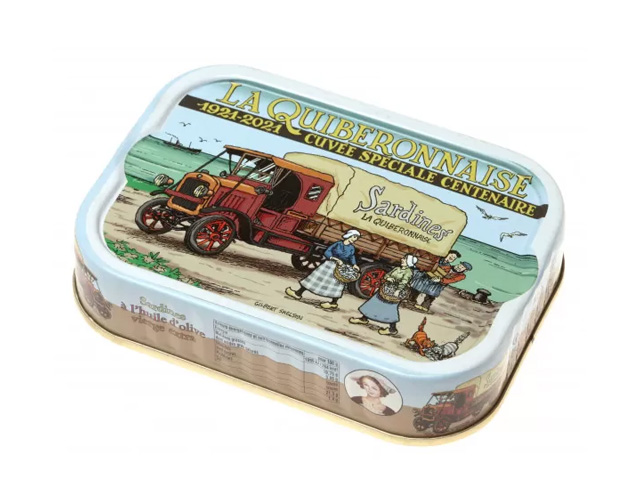

An unmistakeable sign of the impending holiday season turned up this morning in the form of an email from Thierry Jourdan, boss of the family-run cannery La Quiberonnaise in Britanny. Founded in 1921 by Thierry’s grandfather, the fish canning business packs sardines and mackerel landed by local inshore boats as well as taking in yellowfin tuna to pack a range of cans in domestic sizes.

Such canneries were a common sight in seaside towns during the first half of the twentieth century. Today, there are still a number of survivors in what used to be a crowded market. As the fleets dispersed and catches waned, the importance of the tourist trade was recognised by canneries along the French coast. The 1930s saw the establishment of paid summer holidays for French workers: it was the salvation of resourceful canners.

They greeted holidaymakers with open arms and tasteful souvenirs. Local artists are still engaged to create designs for annual editions of elaborately decorated cans of fish, with the promise of a fresh series the next year. Themes range from gently humorous picture postcard subjects to classical offerings that are as likely to end up in an art gallery as a kitchen. Canned fish as an art form has some unexpectedly well-known devotees. Food critic Jean-Luc Petitrenaud always takes a decorated can of sardines for his host whenever he is invited to dinner.