Amazingly, there are still folk around Britain who have failed to grasp the meaning of the words”third country”, let alone why it matters. The Centre for Inclusive Trade reports a 16% drop in British food exports to the EU and is calling for concessions that would be unfair to other third countries. There isn’t a cat in hell’s chance of the European Commission doing a special deal for a former member state that opted to become a third country.

Process of elimination

If there is so much money at stake, how strong is the case for accusing food manufacturers of Ultra Processed Foods (UPFs) of wilful distortion? The arrival of wall to wall processed foods in British aisles in postwar years has been accompanied by rising numbers of patients needing treatment for heart disease and diabetes. While the nation gorges on sugar, salt and saturated fats, there is a drop in foods that bring whole grains, let alone fruit and vegetables. Processing very finely divided ingredients allows fertilisers and other toxic residues to spread downstream through the food chain. More worrying is the uptake of UFPs in the population. These foods now account for 57% of the adult diet and 66% of adolescent food intake. The health issues in later life are already filling up British hospitals and soak up two thirds of the health budget.

Big Food’s Big Secret

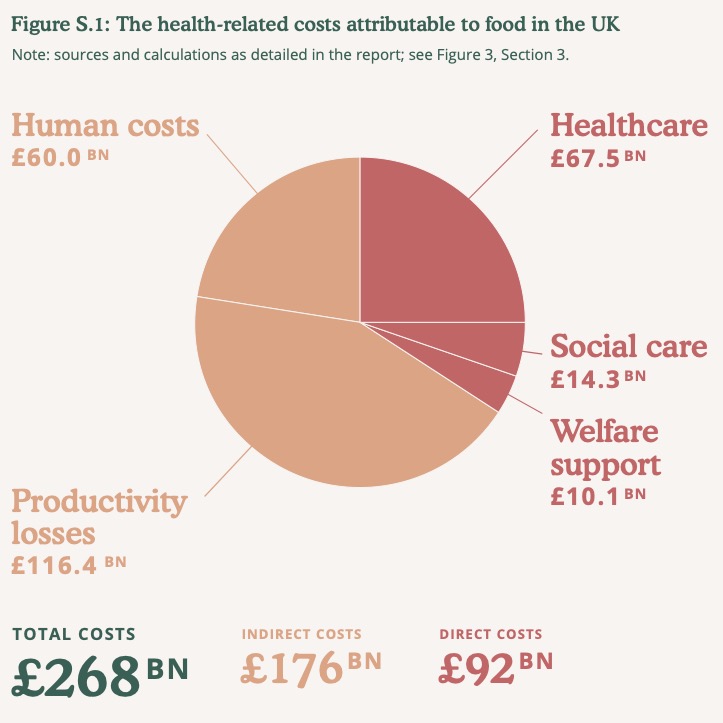

The UK government spends more than GBP 90 billion a year treating chronic food-related illness, according to the Food, Farming & Countryside Commission (FFCC). Researchers estimate that investing half that sum would be enough to make a healthy diet accessible to everyone living in the British Isles. The full extent of the damage caused to the UK economy by a dysfunctional food sector is GBP 268 billion pounds a year, taking lost productivity and early mortality into account, FFCC warns.

The Food, Farming & Countryside Commission is an independent charity, set up in 2017 to inform and extend public involvement in ongoing discussions about food and farming. Using government data as a starting point, FFCC argues that it would be significantly cheaper to produce healthy food in the first place. More to the point, it is not an option to go on footing the bill for damaged public health resulting from the commercial sector’s activities. There is simply not enough money in the kitty and time is running out.

Researchers took into account government estimates of productivity and lost earnings arising from chronic illnesses. These indirect costs are borne by a range of actors in the economy, such as local government departments. Such costs are real expenditure, but the total figure is not recorded as a single aggregate figure. When combined with the initial figures, the result is a more imposing figure and looks like figure S1.

The direct costs (in red) are existing government data; indirect costs (in orange) indicate the economic impact associated with the prevailing levels of unemployment and early mortality. Like the submerged part of an iceberg, we ignore these costs at our peril.

Working with indirect costs opens the door to accusations of misinterpretation, but economists have worked hard to establish methods that can avoid serious pratfalls. Healthcare is supported by a wide range of funding sources, from government down to private individuals. The money is real enough, even when it comes from private individuals. It just becomes harder to count. There are times when budgets for nearby or related units will be skimmed to meet ad hoc requirements. Welcome to the economists’ underworld, where early retirement due to ill health is just another negative variable.

Pink, salty and out of stock

The UK’s high spending foodies have been facing empty shelves, where they would normally find taramsalata. The strike action at a Bakkavar factory in Lincolnshire has successfully kept the salty pink dip out of big name retailers, including Waitrose, Sainsbury and Tesco. These industry heavyweights will get their on back on all those involved in due course — and reduce dependency on Bakkavar by recruiting other suppliers. Here is how the BBC covered the story.

Waiting for salvation

[Please note that this article was published in September 2024] All around the Mediterranean and across southern Europe, thousands of communities are waiting for this year’s olive crop to be milled. Until this year’s production is ready for packing, no new business can be written: there are no reserve stocks available. Every last litre has been sold and there will be no olive oil to sell before the first deliveries of the new crop year reach the market.

For months bulk olive oil prices have been sky high. As recently as August, some desperate buyers in Spain were paying almost 7,000 Euros a tonne for low-grade lampante that would normally have been a fraction of today’s prices. In August, the Spanish industry was forecasting a crop of 1.4 million tonnes of olive oil this year. This “business as normal” bravado is misplaced, since hot weather in the final weeks before the crop is gathered will affect the moisture content and can reduce the yield. In previous years, yields of 20% were average: but until this year’s crop reaches the mills, there is no reliable way of predicting finished tonnages. However, apart from wildfires, there is probably not a lot of additional damage that the environment could inflict on the nation’s olive groves.

The Spanish government is responding to the crisis by cutting VAT on olive oil from 5% to 4%, with effect from 2025. Consumers have seen retail olive oil prices rise from around EUR 3 / litre two or three years ago to hover around EUR 10 / litre now. The unthinkable is happening and Spanish consumers are buying sunflower oil instead of olive oil for home use. Since many households buy cooking oil in small quantities very often, Spaniards have suffered more from the rising prices than elsewhere in Europe. This is because most European retailers place huge orders immediately after the harvest is in, to cover the coming 12 months sales. This fixed price for the year means that retail bottle sizes can have stable prices for the duration, although there is a temptation for retailers to raise olive oil prices anyway, pushing up their margins.

Spain has imported 20,000 tonnes of olive oil this crop year, bringing Spanish consumer consumption and industry intake to a total of 100,590 tonnes. Bottler stocks in August were at an all-time low of 131,740 tonnes with a further 138,660 tonnes held by co-operatives and millers. Total production at the close of this crop year is expected top 820,000 tonnes, making it a poor year. An average season these days would be somewhere between one and two million tonnes of oil.

This year saw a closing of the gap between Extra Virgin Olive Oil (EVOO) and cheaper grades. Paradoxically, strong demand for better grades meant that the market was picked clean, leaving mainstream buyers to pay more for lower quality grades because that was all there was left. Formerly used to fuel oil lamps, as the name suggests, today lampante refers to oil that needs work to return it to an edible grade. This means that lampante has a limited number of takers, since the consignment will need to go to a refinery, adding to the cost and commercial risk.

Delivering results?

Turn the clock back to 2013 and the UK was divided over its membership of the European Union. Given the vehemence of the anti-EU campaigners, buoyed up with sympathetic media treatment, the 4% majority in 2016 was hardly a ringing endorsement for such a major change. The most memorable slogan of the time was “Brexit means Brexit.” Not surprisingly, there were also opportunities to use Machiavellian creativity to plug gaps in the Leave campaign.

It was a time in British politics when the civil service was flexing its muscles and in a position to engineer bids for power with a free hand, actively encouraged by Tory grandees like Francis Maude. Running the Cabinet Office, Maude had a new vision for the Civil Service, which was going to be set free from such tawdry constraints as public service: it was to be redefined and rewritten using People Impact Assessments (PIAs). The Cabinet Office led the way, setting up hybrid public/private joint ventures and mutuals in a bid to gain the best of both worlds, so to speak. These were not just government departments on steroids, these were new power structures of a sort that could be presented as a public service and a commercially savvy business at the same time.

The first employee-driven joint venture was the Behaviour Insights Team (often referred to as “the nudge unit”) which opened for business in March 2013. Here is what was said at the time (https://www.gov.uk/government/news/government-launches-competition-to-find-a-commercial-partner-for-the-behavioural-insights-team):

“The government’s Behavioural Insights Team will take its first step to becoming a profit-making joint venture today as the Cabinet Office launches a competition to find a commercial partner for the business. Less than three years after it was set up in the Cabinet Office the team is the first policy unit set to spin off from central government. This has been employee-led as the staff of the BIT have driven the process and will continue to run the organisation.

“The team was established to find ways of encouraging, supporting and enabling people to make better choices for themselves. Since then it has delivered rapid results – identifying tens of millions of pounds of savings, spreading understanding of behavioural approaches within government, and developing a reputation as a world leader in its field. Demand for its services from within government, the private sector and foreign governments has grown significantly.”

The decade was to see a blurring of the distinction between public servant and executive power. If political factions ever needed to inject reliable, hand-picked people to oversee critical functions in the political process, a joint venture with a government department takes a lot of beating.

Networking and data services have been at the heart of a number of government joint ventures, with the government’s 25% stake being sold off at the end of the first ten years. So it was that the French business Sopra Steria bought out the Cabinet Office’s stake in Shared Services Connected Ltd in October 2023. Here is what they said at the time:

“The transition from joint venture to wholly owned subsidiary will not affect the management, employees, clients, or services of the business, which has delivered significant savings and value for money for the taxpayer.

“Since Sopra Steria founded the company with the Cabinet Office in 2013, SSCL has become the largest provider of critical business support services for the UK Government, Ministry of Defence, Metropolitan Police Service, and the Construction Industry Training Board (CITB), delivering shared services at scale.”

It is not uncommon for IT suppliers to be over-confident about their system’s ability to cope and there are signs that all is not well at the points of delivery in the UK. Dover issued a note to port users in early June, seeking details of operational failures with BTOM. Invoicing for the Brexit border tax has been plagued with errors, including double-billing.

Ten years ago, there can be little doubt that Francis Maude knew and understood the Sopra Steria motto of the day: “The world is how we shape it.” Reality has since dawned on the management and it has been withdrawn.

Taxing times

Time is running out for importers of food to the UK. On September 4 HMRC will demand its pound of flesh and the UK food industry will find itself between a rock and a hard place. This is not the first time that the deliberate destruction of the British economy by the departing government has been discussed on this site: it is still a live topic. Called the Common User Charge by civil servants, the UK’s stealth tax on food imports is also known as the Brexit border tax and doubtless has cruder titles.

Since August 4, many importers have been receiving their first invoices for Common User Charge (CUC. Importers of animal and plant products that would usually be considered for food safety checks can expect to pay over the odds for driving a lorry off a ferry at Dover to join the UK road network. Hauliers booking a DFDS one-way ticket online to Dover pay three pounds for this indispensable service, while lorries carrying grouped consignments of SPS foods face open-ended bills in the hundreds or low thousands for the same access. The simple explanation is that Britain is playing catch-up: the European Union had everything in place to trade with the UK as a third country the minute it ceased to be a member state. Britain was so totally convinced that it would somehow negotiate a favoured nation package Brexit that there was not even a sketchy idea of what a post-Brexit customs system might look like. The years passed, conveniently putting off the awkward moment when Brexit would be complete. As recently as November 2023, DEFRA describes the organisational basis for European food imports to the UK thus:

“Currently, imports from the EU and certain imports from Greenland, Faroe Islands and EFTA countries do not need to enter Great Britain via a BCP and are not subject to veterinary checks at the border.”

(Source: http://apha.defra.gov.uk/documents/bip/iin/vcap.pdf)

Just two months later, Britain was rolling out its three-phase Border Target Operating Model (BTOM). (The label ‘world-beating’ is optional.) Lorry drivers arriving in Britain have not been impressed by the service standards they have encountered on the ground (https://urbanfoodchains.uk/sevington-gives-cause-for-concern/), which is more of a hostile environment than a workplace.

DEFRA has gone from absentee administrator to nitpicking zealot overnight and is chafing over the accuracy of form-filling, notably for consignment detail on Export Health Certificates (EHC). Hang on to your hats, here is a sample:

“Continuous and/or deliberate non-compliance

It has come to our attention, that some traders and logistics companies are making continuous and/or deliberate errors including:

mis-declaring goods as low risk when they are medium;

or as medium when they are high;

not including a relevant Export Health Certificate (EHC) or Phytosanitary certificate.”

Or the consequences… :

“Continued non-compliance within either the EHC or the CHED is not acceptable and will not be tolerated by Port Health Authorities (PHAs). Deliberate misdeclaration is a criminal offence. PHAs will be actively looking to identify such behaviour.

“Where there is repeated non-compliance or evidence of misdeclarations, the appropriate authority will take statutory action. This will result in goods being held at a Border Control Post (BCP) for a physical inspection, which may lead to the consignment being ultimately returned or destroyed at cost to the person responsible for the load.”

Entering a conversation with a tone like that is doomed to become a monologue. Enough said. Now it just remains for the law enforcers to round up a bunch of suspects.

Since the end of April, Dover has been receiving a steady trickle of complaints about the way the Brexit border tax has been implemented. Here is what Dover had to say on the subject, again verbatim:

“As you are aware, the Border Target Operating Model (BTOM) checks have been operational for a month. Aside from initial teething problems, we are receiving a growing number of queries and concerns about how the checks are being carried out versus the costs that are being charged, delays to consignments, poor responses to calls and/or appropriate live assistance with your imports, the impact on biosecurity and the possibility of using Dover BCP to complete checks.

“It is important to understand your experiences so far to enable us to help establish simple solutions moving forwards, so we would like to set up a short call to discuss this with yourselves.

“Please drop us a line outlining your concerns and suggested solutions so we can escalate these for you. In addition, a member of our team may also call you.”

The simple fact is that the CUC started off on the wrong foot and is compounding ongoing problems on the way. It was cobbled together out of retained EU law. Its stated aim is to recover the operating costs of Border Control Posts in the UK, but this does not stand upto close inspection. Officially, CUC rates for privately-owned ports are set by their owners. At regular intervals, DEFRA kicks the distinction into touch by stating that the tax is being charged at Dover and the Eurotunnel terminal.

The port of Dover has belonged to the town since it was incorporated in 1608 by James 1. Some members of the port harbour authority board are appointed by the department of transport, but this is a working arrangement rather than a power grab.

At the beginning of June, Dover issued the following statement, which I cite verbatim:

“We are writing to you with reference to the ‘Operational Border Target Operating Model Information’ Defra circulated on the 03/06/2024 which contained a significant inaccuracy regarding the BCP for high risk food not of animal origin arriving via Dover within the section ‘Moving high-risk food and feed not of animal origin at the Short Straits’.

“To clarify, if you are importing high risk food not of animal origin (HRFNAO) through the Port of Dover, either via RORO ferry terminal and / or deep sea cargo, you must continue to pre-notify Dover Port Health Authority on IPAFFS using the Dover Terminal BCP code GBDOV2P and not, as outlined in the Defra information update, Sevington BCP.

“Official border controls on high risk food not of animal origin arriving via RORO freight have been undertaken at the BCPs in the Western Docks for over a decade and since 2019 at the Cargo Terminal GBDOV2P (in the Western Docks).

“Dover Port Health Authority will continue to provide this statutory function and ensure that your goods are handled efficiently and without undue delay. Please note, the Common User Charge does not apply to the Dover Cargo Terminal BCP. The Common User Charge will be applied if your goods are notified to Sevington BCP by selecting their different BCP code on IPAFFS.”

Dover puts food safety first

Dover port health staff carrying out food safety checks are being sidelined by DEFRA, which is telling importers that their goods should be routed through Sevington. Before shipping certain goods, importers must pre-register the shipment using a system called IPAFFS which is short for Import of Products, Animals, Food and Feed System. DEFRA is telling everyone to delete the Dover port code from the documentation and to change their IPAFFS point of entry to Sevington.

Staff at Dover have been carrying out SPS food safety checks for a decade, but they have never found themselves at loggerheads with DEFRA before. The root of the problem is the Border Operating Model (BTOM), which is not set up to manage product assessments requiring detailed knowledge and experience.

Assigning three levels of risk to food imports does not cover real life situations. Take High Risk Food Not Of Animal Origin HRFNAO, which is a detailed listing of food products that need to be checked for specific hazards. These can include central European blueberries, which are checked for radioactive Caesium 137 from Chernobyl; peanut products from north and south America, which are checked for aflatoxins; or US fishery products, for which processing hygiene standards vary widely.

There is a statutory compliance angle to these product checks, which are regulated by assimilated European laws. At this point they are beyond the remit of BTOM and DEFRA is not authorised to change their enforcement. So instead, the ministry has been advising importers to amend the IPAFFS entry from Dover to Sevington.

In the meantime, Dover port health staff continue to carry out the food safety checks that keep the nation’s food safe.

Moving on

For regular attenders of the Great Taste Awards, this year’s judging has moved to Tipperary in Ireland, to avoid Brexit red tape.

Huffin’ and puffin

From the soaring concrete cliffs of Brussels there is an impending explosion of anger. The reason? Look at Charles Sharp’s impressive picture of a puffin, just about to enter the home burrow with a beak full of sand eels. It is the fish, not the bird, that is fanning the flames, by the way.

For all its comical looks, the puffin is an important indicator in the monitoring of the marine environment around the British Isles. Researchers are particularly interested in the fish stocks that support this distinctive seabird. The term sand eel is a generic label for a group of about 200 fish species that resemble eels but are not related. They burrow into sandy seabeds and hide from predators while keeping an eye out for their own lunch. Hard to catch in open water, they are easy to scoop up in a dredge, as Danish fishermen have done for centuries.

Puffins are far from being the only bird species to be tracked by scientists. It just happens to be the cutest one of the bunch. The puffins’ lunch, by the way, is at constant risk of damage from bottom trawling, that is to say beam trawls or dredgers and other devices. Scallops is one species to be caught in dredgers, while cod is a target species for many beam trawls.

Back in January this year, the UK government announced a ban on dredging for sand eels in UK-controlled Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). For the record, bottom trawling is allowed across 98% of the MPAs concerned, suggesting that the state of the seabed has not been a political priority for years. In the North Sea, with its sandy sea floors, there are still beam trawlers fishing demersal species and small number of Danish dredgers who, between them, hold about 90% of the 160,000 tonne sand eel fishing quota. (UK and EU total)

The origins of the Danish sand eel fishery go back to the soaring livestock holdings of the late nineteenth century, which set the Danes looking for cheap ways of feeding animals. Initially, small dredges were fitted to inshore boats, scaling up in the early twentieth century to purpose-built diesel powered vessels with an ever greater range. For some reason, as with a number of other fisheries, nobody imagined that the fish stocks would ever decline: until, that is, the catches started to drop. With growing numbers of animals on livestock holdings, the potential earnings from sand eels rose, as did the pressure on the fish stocks. Sand eels, along with other oily fish and suitable bycatch, are the ingredients of fishmeal, an industrial end product turned out in large quantities by refineries that earned a living clearing up after the high value fish processors in fishing ports.

In the early days of indoor livestock, fishmeal was added at two thirds to one third cereals. As researchers extended their knowledge of livestock nutrition, the proportion of fishmeal was reduced, making animal feed more profitable or cheaper, depending on your involvement in the process. To ensure an illusion of sustainability for food production in the late twentieth century, the European Commission devised the Common Fisheries Policy, which used its budget to subsidise a rise in the European fishing industry’s tonnage and horsepower, ensuring an ever more unstable fishing industry.

Fast forward to 2024, and the European Commission is threatening to trigger a dispute procedure under the EU-UK Trade and Co-operation Agreement (TCA). The Commission is acting on behalf of Danish sand eel fishers with fishing vessels to maintain. If agreement is not reached by mid-June, the Commission can request a judgement on the UK’s action. While any hearings may be carried over into September, the European Commission is calling for an “evidence-based, proportionate and non-discriminatory” approach to protecting marine environments.

“The UK’s permanent closure of the sand eel fishery deprives EU vessels from fishing opportunities, but also impinges on basic commitments under the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement,” warned commissioner Virginijus Sinkevičius. “Measures are already in place to protect this important species, including by setting catches below the scientific advised levels and closed areas for protecting seabirds,” he added. London responded, saying that DEFRA had not authorised any sand eel quota for British vessels for the past three years. Marine protection NGOs across Europe have launched a campaign to end bottom trawling, which is still allowed in 90% of the EU’s marine protected areas (MPAs). Last year Europe agreed to an EU Marine Action Plan that phases out bottom trawling by 2030. This has some way yet to go.

According to the European Market Observatory for Fisheries and Aquaculture Products (EUMOFA) the EU produces between 10% to 15% of the world’s fishmeal and fish oil output. Tonnages of EU fishmeal range from 370,000 tonnes and 520,000 tonnes, while fish oil ranges between 120,000 and 190,000 tonnes. Denmark accounts for nearly half the EU’s total output. In addition to sand eels, EU processors use small pelagics, such as sprats, whiting or herring, all regulated with quotas and topped up with trimmings from fish processors. EU demand for fishmeal has dropped in recent years and is currently hovering around 450,000 tonnes/year.