The economy often appears to be a large, ramshackle institution, a law unto itself. This is partly due to the skills of those who really control it and partly because it is both a large ramshackle institution and a law unto itself. If the economy was only made up of money, it might be easier to make a case for saying that it can be controlled, if not managed, at some level. The truth is that the economy comprises much more than mere money and is constantly manipulated by economic factors that strengthen the relative strengths of one component over another.

Pricing experts?

Ask any economist and they will tell you that economics is a science, founded on mathematics and using none but the most reputable methodologies known to data science. The acid test of any scientific discipline is to be able to replicate previous experiments and repeat the results to within an acceptable margin.

To be sure, if you take the same data and crunch the numbers using the same calculations, you will get the same results as the previous economist. But economists are a diverse bunch, not to mention the smørgesbord of economic policy recommendations to be shared as the opportunity arises.

If this sounds less than serious in its tone or intent, it may be that it is not written by A Proper Economist (always spelt out in full, never abbreviated). A Proper Economist can be relied upon to analyse market data and forecast the likely price trends within a given sector. If, on the other hand, you wanted to know the retail price of a grocery line for the coming year, that would be a closely-guarded secret between a supermarket buyer and her (or his) supplier.

With the digitisation of the retail checkouts in the early 1990s came a tidal wave of sales data that probably paid for itself in months, if not weeks. For the first time in recorded history the multiples knew exactly how many units of which lines they were selling; where they had multiple suppliers of own-label products, the multiples could start to make direct comparisons between suppliers and the margins they were generating. Individual suppliers knew what volumes each was shipping to retail customers, but only the category managers had the whole picture.

The supermarket buyers’ secret weapon of choice in those days was a miniature tape recorder and microcassettes, to which verbal contracts worth millions of pounds were recorded. If any hard copies were ever made, these would have been kept in a safe. Supermarket buyers and category managers are overlapping roles. They were always instantly recognisable at trade fairs, leaving suppliers’ stands with their tape recorder pressed to their ear, playing back the small print as it was wrung out of the supplier. There was no question of suppliers passing on price increases arising from higher prices on the international markets: the standard response in those days was: “find cost savings in your business…”

Not that buyers ever applied that principle to their own dealings with suppliers. Food manufacturers presenting new ranges and products to multiple retailers would face requests for a listing fee and, often as not, a request for special offer stock. Listing fees were also referred to as hello money or shelf money, among other names. They used to start around £5000 per SKU for listings in an agreed number of outlets. Shelf money was never refunded if a product was delisted, but would be requested for years to come during the life of the listing.

Special offers were not what they might have appeared to be, either. The retailer charges the consumer for the special offer part of the price. But does the multiple give away the offer component of the price? Hell no! They recovered that from the suppliers, who systematically funded the offers, providing free stock directly or having the equivalent money withheld from invoices for other products. Either way, the retailer banked the full price on special offers. From the retailer’s point of view, it is having your cake and eating it. Even though the Grocery Code Adjudicator’s office has cleaned up the retailers’ act, the industry is still haunted by the ghosts of past sales targets.

The value of money

Before we roll up our sleeves and dig into the serious business of food pricing, we need a way of converting LSD to pounds to two decimal places, among other things. Here is an inline WordPress calculator courtesy of the Calculated Fields wonder plugin. My first idea was to provide a digital scratchpad with which to convert one-off figures.

[CP_CALCULATED_FIELDS id=”7″]

As part of the process, I also wrote a spreadsheet to do more heavy lifting, which is now available to logged-in users using the download link in the housekeeping menu box.

However, we need to do more than calculate the face value of old prices, we also need to translate the value of the currency of the day. The problems arising from trying to apply a one-dimensional measurement to a multidimensional world range from the practical to the arcane and I quite understand that not everyone will be keen to engage with them. One of the first is to decide which parameters are relevant and whether any of them are of universal application, regardless of whether or not such parameters are measurable.

What the official data looks like

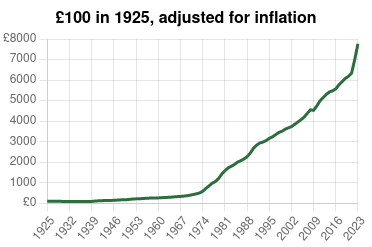

Ian Watson, who developed the website Official Data [dot] org, has assembled government data from western economies in a bid to quantify the huge losses in their currencies’ historic spending power from the 1970s on. Working from national government data, Watson plots the value of 100 pounds from 1925 to the present day and found the 1925 hundred pounds to be worth around 7,700 pounds in today’s money. He found a similar pattern in the US, Australian and other major industrial economies. The graph for the UK is dramatic: clicking it will take you to the relevant page on Watson’s website.

Food pricing 100 years ago

The 1925 Royal Commission on Food Prices was tasked with investigating food industry prices. Urban Food Chains is running a series of analytical case studies for subscribing members, drawing on the detailed statistical evidence that was heard by the commission during its deliberations.

Board of Trade statistician Mr A W Flux* told the hearing that the UK food economy grew by about two billion pounds (thousand million) in 1907. This comprised goods consumed in the UK , which were valued at between 1,248 and 1,408 million pounds; services between 350 and 400 million pounds and additions to capital of between 320 and 350 million pounds.

2. Of the goods consumed, some passed directly from producer to consumer (e.g. bread), and in some cases the produce was consumed by the producer (e.g. farm and garden produce consumed by the families of the cultivators). A second class of goods, while passing through merchants’ hands, was not the subject of retail trade, while, of the goods that passed though merchants’ and retailers’ hands, it was estimated that the charges of distribution, including cost of transport, amounted to something between one half and two thirds of the value of the goods at the place of production or importation.

The First Report of the Royal Commission on Food Prices, Volume 3, Appendix 1, paragraph 2

*Mr Flux is not a made up name, it is for real.

Follow the links for subscription-only content about the core commodities of the day:

| bacon |

| bread |

| butter |

| cheese |

| eggs |

| fish |

| flour |

| fruit |

| ham |

| milk |

| sugar |

| tea |

| vegetables |

| wheat |

Fighting over food

The truth is unlikely ever to emerge from the rubble of world war two, but the British ruling class was convinced that there was a significant black market trading in the wartime British Isles. The obsession with even the possibility that spivs might be getting away with crimes against upstanding citizens is captured by William Sitwell in his book Eggs Or Anarchy.

At this time, the House of Lords could be relied upon to make the most fuss over the least incident supported by little or no evidence. The sensitivity of the establishment to the idea that people might be getting away with crime, be it real or imagined, beggars belief. One particularly paranoid peer accused Lord Woolton, then minister of food, of failing to act in a timely manner to pre-empt the spread of profiteering, which he now believed to be out of control.

Woolton was, of course, held responsible for this state of affairs, be it real or imaginary. A man of humble origins, his arrival in the upper house was a reflection on his achievements in business rather than his birthright. To be sure, he was as irked by tales of black marketeering as his fellow peers, yet he was to be judged on getting results that were far from being attainable.

The National Mark

In 1934, the Ministry of Agriculture published a recipe collection based on ingredients produced to National Mark standards, a fundamentally flawed quality assurance scheme overseen by the ministry. In 1936, the ministry went on to publish a second National Mark booklet with a year’s worth of recipes and product information, couched in the most toe-curling and sexist language imaginable.

The National Mark Calendar of Cooking is a 128-page stapled booklet, published in 1936. It contained recipes compiled by cookery correspondent of the News Chronicle, Ambrose Heath and Good Housekeeping Institute director Mrs D D Cottington Taylor.

It addressed an affluent upper class readership, heaping unstinting praise on British-grown food and overlooking the fact that the UK depended — and still does in large measure — on imported food. As the rest of Europe prepared for war, the National Mark Calendar warbled and wittered on endlessly about products that were only available to a rich elite.

Recipes for June include such gems as semolina souflee and poached eggs in aspic.The souflee recipe gives instructions for cooking the dish in a hot oven or a steamer, should a suitable oven be unavailable.

Piece of cake?

The food industry celebrates “meal occasions”, which are excuses to buy and eat food without necessarily qualifying as a meal in its own right. Irish food manufacturer Glanbia suffered a setback for the VAT status of its flapjacks in April when a tribunal decided that the range did not qualify as a cake and was henceforth to be taxed at 20%.

The case hinged upon the suitability of the chewy confectionery bars for serving at afternoon tea. Cakes qualify for zero-percent VAT and a substantial fruit cake would still be classified as cake even if its mouth feel is distinctly heavier than a Victoria sponge.

Many years ago, the makers of Jaffa Cakes mounted a successful case to argue that as the name implied, their product was eligible for a zero-rated VAT status. A patisserie chef was hired to make an oversize Jaffa Cake and field questions from the tribunal, which accepted the basis for the distinction.

Glanbia, it would appear, was not so fortunate. Members of the panel declared that the flapjacks did not earn a place on the table at teatime because they are too robust. English tea is where you have your cake and eat it.

Here is how The Guardian covered the story: https://www.theguardian.com/law/2022/apr/17/flapjacks-too-chewy-taxed-cakes-judges-rule-glanbia-milk

Pig sector still struggling

Despite some welcome signs of change in the fortunes of the pig industry, there are some ominous long term indicators. slaughter weights are starting to ease off from January’s high point. But at about 94kg deadweight, this year’s slaughter pigs are still five kg a head more that this time last year.

Welcome news from Morison’s when the retailer raised its contribution to production costs (SPP) by 30p to GBP 1.80. Pig producers need more retailers to do likewise. More to the point, producers need a more reliable system for recovering their cost of production, just to stay in business.

January pigmeat imports totalling 83,000 tonnes were up over 20% in December, not to mention double the volumes imported a year ago. Bacon imports in January were 27,000 tonnes, compared to 9,500 tonnes a year ago and 17,500 tonnes in December.

Market trends like these spell trouble for UK pig producers.

Since writing this piece in the spring, the AHDB has reported a recovery in market figures to nearer normal levels. However, this does not mean that pig farmers are any better off than they were earlier in the year.

40k and counting

Delegates at the National Farmers’ Union conference at the end of February learn that at least 40,000 healthy pigs have been culled and taken out of the food chain because of a continuing failure by abattoirs to collect and slaughter all the pigs they contracted to take last year.

Pig farmers up and down the UK are struggling in an ongoing crisis that is leaving hundreds o pigs a week on farms, eating food that is hitting record highs. The BBC cites a Norfolk farmer (https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-norfolk-60516864) who is sending 200 a week out of his 300 contracted animals, leaving him with 100 more pigs every week to feed. They eat 10.5 kg of feed a day ad by the time they are finally killed, they will have eaten an extra quarter of a tonne of feed. This is unplanned buying for the animals concerned, at a time when feed is at an all-time high and wheat prices are well over GBP300 a tonne.

Why pig slaughter weights matter

Since the end of October last year average pig slaughter weights have been rising steadily, hitting 95 kg during the week ending January 8, 2022. This is about 5kg above the long term average. This is due to abattoirs refusing to take all the pigs they contracted for at the beginning of the breeding cycle. Processors face a shortage of skilled labour in the killing lines and boning halls, with the result that pigs being held back on farms.

[chart to follow]

Here, they are eating feed that was not costed into the business and since UK male pigs are not routinely castrated, they are increasingly likely to pass puberty and be affected by boar taint with the onset of breeding condition. This renders them unsaleable and inedible.

The weight of a pig at slaughter is critical to its commercial value, since overweight pigs put on fat in the muscle tissue and their conformation is no good for retail or foodservice clients.

A week later and no sign of any change.

British pig prices dropped even further in the week ending January 15. The Standard Pig Price (SPP) dropped to 139p/kg, the lowest it has been for almost a year. Pig producers are still looking after pigs that should have left their holding long ago, as the average carcase weight set a new record at 95.42kg (source AHDB). Since these animals would normally have left for slaughter, farmers are having to buy grain on the spot market, pushing feed prices up in the process.