Urgent requests for government involvement in setting up the commercial infrastructure that would be needed for trading as a third country after Brexit were mostly ignored, according to pig industry body the National Pig Association (NPA). In November 2020, with less than two months before the end of the transition period, the association had “…a long list…” of unanswered procedural questions for the export of breeding pigs and pork products after Brexit.

While the NPA continued to work closely with the environment ministry DEFRA, NPA chief executive Dr Zoe Davies warned that: “…time is now running short and we need more urgency and engagement from across Government before it is simply too late.”

She observed that the UK pig sector faced the very real prospects of being unable to continue the vitally important trade in breeding stock to the EU and of severe delays, as well as higher costs and reduced market access for pork exports. “The impact could be devastating,” she warned.

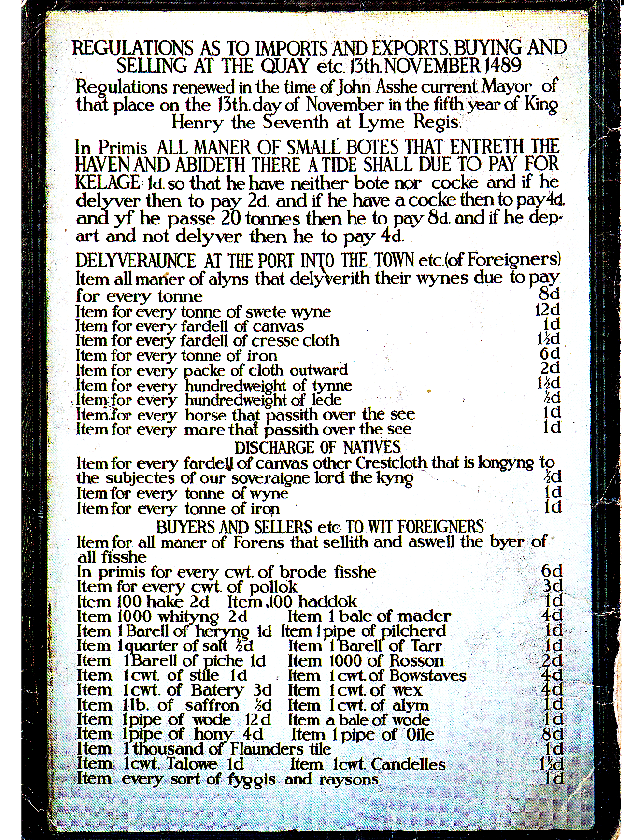

Some of the unanswered questions required solutions regardless of whether or not there was a Brexit agreement in place after the transition period. Topping the list was a lack of Border Control Post (BCP) facilities in key European ports for live pigs and in some instances pork products. Once the grace period ends for customs health checks on imports, serious doubts persist about the availability of qualified veterinary professionals to process a tidal wave of additional certificates. The NPA estimates that the paperwork alone will increase fivefold.

“We are still waiting for an indication of whether or not the significant extra veterinary resource required can be met,” explains Davies. In 2020 DEFRA told the NPA to persuade the key EU port authorities to invest in the necessary BCP facilities and left the association to its own devices. “There has been no interest from the Government in helping us engage at either Commission or Member State level.”

The required investments in BCP facilities will also be required for consignments arriving in the UK once the transition period is over. “There are no seaport BCPs in the UK at present either,” explains Davies.

“Defra has pointed out that, as it is phasing in import checks, these won’t be needed until July 2021. However, we will need to know well in advance what the exact requirements will be for testing and inspection, while any port operating as a BCP will require time to put the necessary infrastructure in place.” The financial commitment involved is significant: it includes specialist veterinary staff appointments as well as buildings and laboratory facilities.

A further practical consideration that was still unresolved at the end of the transition period was transport. “Hauliers will require separate authorisations and qualifications in both the EU and UK. There is still a complete lack of clarity as to how companies will be able to register and hold multiple authorisations without adding huge cost.”

The operational impact on the slaughtering and processing sector of losing large numbers of qualified non-UK EU vets is not a new concern. The issue was raised in the House of Lords report number 15 published during the 2017-8 session of Parliament. (https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201719/ldselect/ldeucom/15/15.pdf)

This post first appeared about 10 days before Christmas. Today, December 25, it is clear that the government has learnt nothing from this episode; there is a lingering temptation to suggest that this was the intention all along. More than 30,000 healthy pigs have been culled at the expense of pig producers up and down the country. Many of them have gone or will go out of business through business through no fault of their own.