Towards the end of the twentieth century, the UK was importing about a quarter of a million tonnes of cheese a year.

What “by numbers” is about

Across this website, readers will have seen posts such as butter by numbers or cheese by numbers. The purpose is not spelt out in these posts, so here is the thinking behind the “by numbers” coverage.

First, most of the figures cited go back to the end of the 20th century and are volume measurements. The choice of tonnages over the more usual measurement of currency is intended to give an idea of the additional capacity that imports generate for their economies.

In its simplest terms, importing food occupies production capacity the exporting country cannot use for the local economy. For countries like New Zealand, rural populations are so sparse and urban populations are so far apart that this is not a problem.

Market gardeners close to urban centres in countries such as Kenya, on the other hand, can find themselves left with crops of green beans for which they have no local outlet. Having promised to grow premium vegetables for affluent industrial economies, there is no wriggle room for producers if retail customers change their minds.

By looking at tonnages, it becomes possible to calculate the agricultural resources that are occupied by export production.

The use of data going back to the late 1990s is a reflection of the fact that multiple retailers invested heavily in electronic point of sale and data management for food sales during the early 1990s. The later years of the 1990s mark the moment that the results started to become visible.

Butter by numbers

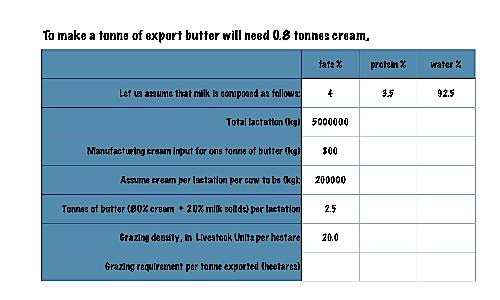

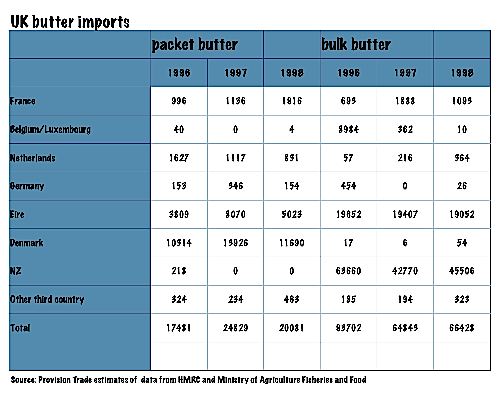

A cow producing 5000 litres of milk in a lactation (a lot by the standards of the 1990s) would give enough cream for two and a half tonnes of butter. Converting the remaining output into skim milk powder (SMP) would add a further couple of tonnes of powdered milk to the final output. There are other ways of splitting up milk fractions, some of them with limited use and application. Some standard variables appear in the first table, while the second outlines UK butter import tonnages for packet butter (retail product) and bulk butter for 1996-8, when the Common Agricultural policy was in full swing.

Taking the 1998 total packet butter imports total of just over 20,000 tonnes and when the total is divided by 2.5 (tonnes per lactation) it becomes clear that you will need at least 8,000 lactations — or lactating cows — to generate this tonnage. Bulk butter imports for that year topped 66,000 tonnes, needing a further 24,000 cows. Figures on this scale pose two serious questions.

First, is the UK economy capable of generating sufficient demand to increase domestic production by a comparable tonnage? Second, where would the UK accommodate an additional 30,000 dairy cows and the same number of calves that would trigger the necessary lactations? The chances are that the UK economy is not vigorous enough to generate investments in domestic production on that sort of scale. It is equally probable that the UK landscape would not absorb thousands of additional cattle and their calves.

The attraction of imported stock such as bulk butter is that it can be diverted into seasonal products like mince pies, which are planned into shifts after Easter and stored in a freezer until needed in the run-up to Christmas. Energy prices have made this pattern uneconomic this year, but it was a successful venture in previous years.

Butter comprises 80% cream and is transported in a refrigerated system. If there is no refrigeration, butter can be clarified. The process removes the water and heat sensitive protein, turning it into ghee. This can be kept in hot climates at ambient temperatures.

Milk by numbers

Milk is around 90% water, so it makes sense to stabilise it as butter or cheese or milk powder before trying to move it anywhere. A good example would be New Zealand, which has a network of butter/skim milk powder plants, where milk is centrifuged to extract the cream. This is made into butter, while the remaining skimmed milk goes to a drying tower and leaves as skim milk powder (SMP).

The UK has a tradition of marketing its milk as liquid milk, which is either pasteurised, sterilised or put through an Ultrahigh Heat Treatment (UHT) line. UHT cartons will have a life of around a year at ambient temperatures, sterilised milk should be protected from the light, but will last indefinitely in unopened bottles.

Using a centrifuge, milk for pasteurisation or UHT lines will be standardised at 4% or 2% or zero percent for full cream; semi-skim or skim respectively. Surplus cream is usually collected in a tank for sale on the industrial market. A milk packing plant can quite easily generate a tanker load during the course of a week, for most of the year, with the exception of a Christmas peak in UK sales of cream. Before Brexit, tanker loads would often travel as far as Germany and be a viable proposition.

Milk powder footnote

All milk for powder making must be centrifuged before it goes through the drying tower. Any remaining cream or protein would block the fine nozzles used to spray the milk into a rising column of hot air. The fat-free Skim Milk Powder is collected from the bottom of the tower.The fat content is restored if there is a need for Whole Milk Powder or a custom formulation for food manufacture or baby foods.

Cheese by numbers

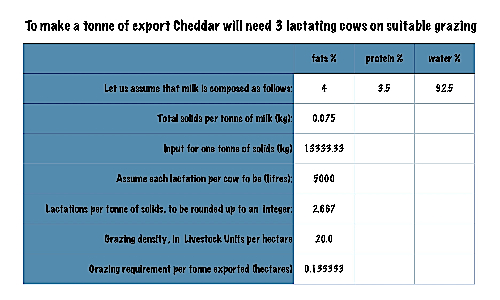

When you come to realise that milk is made up of water — 90 percent or more — it becomes clear that it needs to be turned into something a bit more user-friendly to be transportable. Making cheese has routinely been a convenient way of stabilising fragile milk and preparing it for a longer journey to its end user. Milk proteins will be retained and a proportion of the cream will be either removed or additional cream will be added, depending on the recipe. Cheddaring cheese is basically a technique for extending the working life of milk, using the existing solids. The progression is laid out in the table below.

Having made curd with the milk, there is inevitably some loss of the finely divided protein particles that are retained in the whey. The whey was traditionally fed to pigs, which is why the history of livestock farming in Denmark was so closely integrated. A significant component of Danish bacon in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries started out as whey from cheesemaking.

Depending on the density of grazing livestock — the example here assumes 20 lactating cows to the hectare — there will always be a certain amount of agricultural land that will be blocked from local use by the commitment to export the production it supports. This is a topic to which we will return. For now, it is sufficient to assume that dairy producers will need three lactations (integer values) for every tonne of milk solids that are recovered and transferred into cheesemaking. In addition, there will be a need for three twentieths of a hectare of grazing land to meet the Livestock Unit level in this model.

There is a greater diversity among cheeses, reflecting their moisture content and how the whey is removed during the cheesemaking process. As a cheese ages, it will go from being a crumbly wet curd and solidify into increasingly dense cheeses. Whole cheeses are matured for up to two years in the case of hard cheeses like parmesan or Grana Padana, a year or more for mature grades of Cheddar, to just six weeks for soft cheesses like Camembert or Brie. The protein can be more or less elastic, depending on how much heat has been applied to the curd and other factors in the process.

Selling directly

“Today, we have come to sell our produce for a fair price,” declares Gérard Ricardi. The secretary general of radical farmers’ union MODEF (MOuvement pour la Défence des Exploitants Familiaux) has plenty of takers for tomatoes at EUR 1.50/kilo outside the mairie [town hall] of Ivry sur Seine on a blazing hot morning in late August.

The supermarkets pay around 45 centimes/kilo for tomatoes that cost 70 centimes/kilo to grow, Ricardi explains. There is 20 centimes/kilo to find for transport and packaging, before the same tomatoes are sold in Paris for EUR 2.50/kilo.

“Prices like that are a racket,” he grumbles. “Here, the growers are earning 70 centimes/kilo, there’s 20 centimes/kilo freight and packing, with 60 centimes for the distributor.” Total EUR 1.50/kg.

“We want to make it clear that there is scope for everyone to earn a living. The state should face up to its responsibilities and support consumers and growers alike.”

Sixty years ago, the French state imposed a maximum retail margin on agricultural products. “The state recognised then that retailers were overcharging and took action to stop the abuse.”

Known as the coefficient multiplicateur, retailers were able to multiply their cost prices by a factor of between 1.5 and 1.7, but no more. “The grocers were just lining their pockets, but it was not acceptable then in the way it is now.”

In fact, this policy had two important benefits: “Consumer prices were lower, because prices were linked to growers’ production costs and growers received a fair return for their work,” Ricardi observes.

“There was even a shared interest for retailers to pay more to the producer, so that the retail price could be higher. It was a virtuous circle that worked for consumers and producers, too.”

The coefficient multiplicateur lasted until 1986, when the retail lobby finally managed to kill it off. In recent years, a watered-down form of the coefficient multiplicateur returned to the Code de l’Agriculture as an emergency measure, but it has never been implemented because there is simply no political will to question the integrity of multiple retailers.

MODEF is celebrating its 50th birthday this year. MODEF was founded to stand up for small family farmers at a time when the mainstream farming unions would have cheerfully excluded six million peasants from the political process. Today, the largest union FNSEA uses the word paysan (peasant) to pluck the heartstrings of a nation that has very varied notions of a time before industrial farming, which should somehow have been better than today but probably was not.

Against all the odds, MODEF is still fighting the same assumptions in harder times. There are fewer peasants – just under half a million – but the growing power of a handful of multiple retailers has become a stranglehold on the nation’s food supply.

“We are disappearing and the head of state takes us for a bunch of idiots,” growls Girardi. Around him are crates of nectarines, plums and melons, fruit on which supermarkets earn similar margins to the tomato bonanza he described above.

“They’re buying my potatoes for 5 centimes a kilo,” another producer chips in. “They cost me 20 centimes a kilo to grow.”

As he speaks, just 100 metres away a French-owned discount grocery chain is selling 2.5 kilos of potatoes in a net for EUR 2.99. At 13 locations around Paris, there are queues to buy MODEF-produced potatoes priced at EUR 4 for a 5 kilo net.

The previous night, the growers had loaded an articulated lorry with tonnes of potatoes, melons, tomatoes, nectarines, plums and salad grown in Lot-et-Garonne before driving to the French capital to sell directly to Parisian consumers. Not that the public needed a lot of convincing.

The prices speak for themselves: two lettuces for EUR 1, compared to EUR 0.99 for a single lettuce in the same French discounter, while MODEF nectarines were priced at EUR 2/kilo against the retailer’s EUR 2.29/kilo.

At a local shopping centre a bit further away, Spanish grade II tomatoes are being sold in a larger supermarket for EUR 1.09/kilo. MODEF growers are not alone in resenting the kind of market distortion that arises from a European directive that has allowed countries such as Germany and Spain to exploit cheap foreign labour and undercut growers elsewhere in the European Union.

“The Bolkenstein directive must be revoked as a matter of urgency,” says MEP Patrick Le Hyaric, who was present at Ivry sur Seine. “This directive has allowed Spanish growers to take on Moroccan farm labourers and pay them less than the minimum European salaries,” he declared.

As a member of the European parliamentary commission for agriculture, he had just returned from Lot-et-Garonne where he had met a delegation of fresh produce growers, some of whom were on the same improvised market square at Ivry sur Seine. “I knew the situation was difficult, but now I have a better idea of the scale of the crisis that is gripping the small and medium-sized holdings in this sector.”

Over the past 20 years, Lot-et-Garonne has already seen a lot of growers go out of business. “Today, those that remain do not know if they will still be standing in six months’ time,” warns Le Hyaric.

He is organising an urgent meeting with the French minister for food, farming and fisheries, Bruno Le Maire, to demand emergency aid packages for growers and the urgent implementation of the coefficient multiplicateur. This is available as a crisis measure but has been studiously avoided by the French government.

“In its present form, the Common Agricultural Policy has a number of negative effects. But in its original form, it was a sound piece of policy. The préférence communautaire was not a bad idea, it just did not fit in with ultra-liberal ideas or the so-called ‘free market’, that is all.

“So Europe gave in to US demands. And now, for instance, France is completely dependent on imported soya to feed its livestock, most of it from Brazil.”

As long as cheap food imports can be procured around the world, consumers in the industrial world can get by without small, local food producers. But abandoning an entire sector of the economy has a cost that should be neither underestimated nor trivialised.

It is neither a secret nor is it difficult to understand. Talk to anyone who sells food direct: just don’t leave it too long.

Are we ready for insects?

We are told by industry sources that there are more than 1,900 species of edible insects. There is no simple way of checking this figure or defining what is considered edible or not… Despite having such a broad palette to choose from, most manufacturers go for three easily recognisable species: mealworms, crickets and grasshoppers. In keeping with the crunchy post-processing state of the insects, it is hardly surprising that there are lots of crispy snack products to choose from.

Good news for the squeamish: insect products will keep for about a year in a cupboard, longer if the contents are clearly labelled. The allergy risks are similar to those encountered with shellfish and the pack sizes are modest.

Insects are good value for money, though. You can extract 60g of protein from 100g of insects, whereas you would have 55g from 100g of beef. There are environmental discussions to be had about insects, too. Smaller environmental footprint, rapid source of protein and traceable with it. Hmm…

A broken system

The Environment, Farming and Rural Affairs select committee (EFRA) has recently published its findings on staff shortages in the UK food industry. It frames the problem as half a million unfilled jobs in a sector with just over four million workers.

The pig industry and field crops are judged to have been hardest hit: government measures to counter a crisis situation were branded as “too little, too late” by those in the sectors concerned and there is little reason to suppose that the government has learnt a great deal from a crisis that is taking agricultural businesses off the map.

The covid pandemic is trotted out as a major contributing cause of the crisis, but as early as 2017, EFRA was hearing evidence from UK veterinary experts that Brexit would cause consequential and structural damage to UK agriculture. This damage is being done, but Brexit is not being blamed for it.

For all the positive noises coming out of EFRA over the government’s welcome measures to make it easier for UK businesses to recruit specialist food industry workers, the stage is set for a chorus to emerge from the wings and narrate the closing scenes of this very public Greek tragedy as it unfolds.

The UK food industry generates GBP 127 billion a year – more than 6% of the Gross Value Added to the national economy. It should be added at this stage that this figure for the sector includes multiple food retailers and their staff.

The National Farmers’ Union reported that a 33% gap in the work force meant that 24% of the UK daffodil harvest went unpicked, while one in ten growers in the Lea Valley Growers’ Association did not sow a third cucumber crop in July 2021, for the lack of people to pick the crop.

Fresh produce producer Riviera Produce Ltd left produce valued at half a million pounds to rot in the fields, while Boxford Suffolk Farms ltd reported that it lost 44 tonnes of fruit due to labour shortages.

The British Meat Processors’ Association warned that its members faced a shortage of more than 15% in staff numbers, while the National Pig Association reported a “…desperate lack of skilled butchers…”, while pig farms were facing serious gaps in their work force. The British Poultry Council went into the summer of 2021 facing a gap of 6,000 staff among its members, in a sector that employs the equivalent of 22,000 in full timers.

There is no reason to suppose that any of these important industry figures is making up or overstating the problems they face. But they all need rather more than a figurative pat on the back and meaningless platitudes.

The report HC713 Labour shortages in the food and farming sector can be consulted online or downloaded at https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/9580/documents/162177/default/

Milk prices set to take off

The farmgate milk price has risen by nearly 24% during the year ending March 31, 2022. For most of this time, prices tracked the five-year minima, but started to rise steeply from January and into February, closing the gap on five-year highs as the spring flush appears on the horizon. This is the time of year when the majority of UK dairy farms plan for calving, since there is usually strongly growing grass and the longer days promise more favourable weather for the next generation of cattle.

With a high proportion of cows starting a lactation in a normal year, milk volumes would go up, reaching a peak later in the summer. A slower start to the spring flush is a marker for a more difficult year, while the rising farmgate price gives cause for concern, since it would suggest that there are fewer lactating cattle to supply the market.

There is, however, another factor that will push producer prices up. The UK dairy industry has a lot of milk tankers on the road and unprocessed milk is a high mileage market. Steep rises in fuel costs will also impact the headline producer price of milk. source

Producers get a grip on their markets