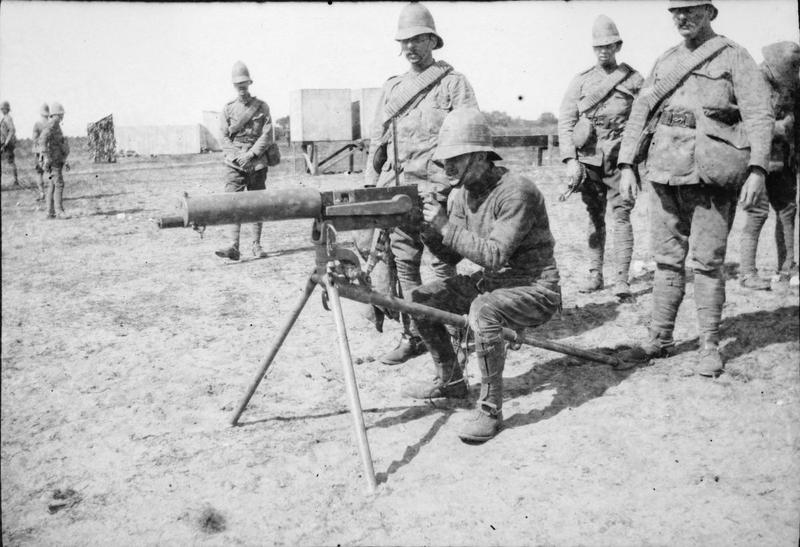

Starting with the Boer war at the turn of the twentieth century, the impact of heavy machine guns was devastating on industrial battlefields, where thousands of horses were culled. The effect on the British economy was immense and immediate owing to the huge numbers of working animals needed to move equipment such as artillery from one site to the next. Such basic tasks became lethal interludes, as enemy machine gunners could take out the lead pair in a team of six or eight, immobilising the equipment, the surviving horses and the hapless soldiers who had to sort out the situation and salvage what was recoverable.

Horses and other pack animals were valued more highly by the British general staff than the rank and file soldiers of the day. The loss of thousands of horses was a problem for manufacturers everywhere, especially those who needed to provide local delivery services for their customers.

You can reckon that horses would have been expected to carry up to twenty percent of their body weight. Their harnesses may not have been taken into account, but would have been a significant proportion of the loaded animals’ burden. Establishing the loaded weight of a pack horse allows us to make some very rough and ready comparisons between the horses lost to the war effort and the rising numbers of two and three ton commercial vehicles that started to appear on British roads in 1914.

The power output of the early lorries used in opening years was fairly low for the most part, around 10 horsepower. You could say that every lorry did work that would have taken a team of six or a team of eight horses. In doing so, it is important to establish more than one set of parameters to make the comparison useable. It is fair to add that the power output from commercial motors increased rapidly from the late 1920s, this can readily checked by consulting contemporary advertisements. Despite its years of international power and influence, Britain was a net importer of horses between around 1860 and the 1930s. This not only stressed the economy, it makes valid comparisons between machinery and horses hard to establish.

It is quite likely that vehicle purchases made by the British government throughout the war years contributed to greater volumes of lorry traffic on British roads attributable to registered vehicles. Even if a high proportion of military vehicles are not registered through civilian agencies, what matters is that the total pool of vehicle tonnage was boosted in the process. Wartime government purchases of 20,000 vehicles will have added about ten million pounds to the postwar development iterations of the next generation of commercial motors..

Leave a Reply