As the world’s most recent third country, UK food exports are at the receiving end of thorough checks on entry to the EU. All animal products are allocated risk levels and inspected accordingly; plant material undergo a parallel set of phytosanitary (plant health) checks. For UK exporters, the administrative overheads of complying with food safety standards were a known quantity long before the January 2021 transfer to third country status when UK shipments were routinely checked in Border Control Posts (BCPs).

The UK has yet to carry out its longstanding commitment to implement a mirror image system with the same inspection protocols for food shipments coming into the UK. Until that happens, Brexit is no more than a work in progress, not a done deal.

At the time of writing, the UK government is poised to kick border checks on into the long grass for the fifth time, delaying the full complement of checks until autumn 2024. This should come as no surprise, given the gaps in government resources.

Westminster is wrestling with a structural shortage of vets who are authorised to issue valid health declarations. This was a known issue in 2017 when a House of Lords select committee warned of a vet shortage, among other things, in its report Brexit: plant and animal biosecurity Over the past few years there have been a number infrastructure modifications at UK ports to house BCP facilities. The situation is complicated by the fact that around the UK not all ports are in public ownership and many have hybrid management frameworks. For some, the fabric of the port is its capital, meaning that a parliamentary bill may be required to underwrite loan capital for major infrastructure investments. This is only one factor among many that has cooled the government’s will and ability to act, however.

The UK food industry is caught up by its own reluctance to make the transition to full food safety checking at internal borders. This is not a public health issue so much as a tangle of red tape and knowledge gaps. At any given time of the day or night, there will be dozens of lorry movements up and down the country, heading for Northern Ireland. Leaving aside the unionist arguments against having a border check where none should be required, there is potentially a grittier problem to resolve.

There is a lack of old-fashioned stock control clerks with previous experience of customs documentation. The real problem is that the documentation travelling with a load is closer to a customs valuation than a handlist for whoever has to unpack the roll cage when it arrives instore. The stock in trade of an RDC (Regional Distribution Centre) is a loaded roll cage with dozens of SKUs, more or less stacked in the order they were picked. This is adequate for England and Wales, but is not a promising start for goods which may need to be inspected on a line by line basis in a customs shed.

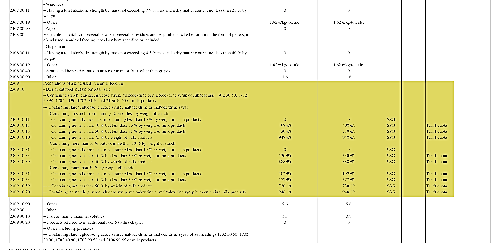

The rules for calculating a customs valuation are clear and there are a number of ways in which a customs valuation may be arrived at, each with its own methodology. Think of the process as HMRC making a window into a retailer’s accounting system and then discovering anomalies with earlier figures. These could arise from the ways in which shelf money is managed or have an innocent explanation, but making a case to HMRC for a wide gap between a low customs valuation and a full retail price is not what people want to spend time on just now, if at all.

The additional cost of physical checks just adds to the awkwardness of the situation. The UK government is preparing to run documentation checks on inbound animal products for just over GBP 30, but is fighting shy of publishing a price list that would put physical checks into the six or seven hundred pound bracket. These inspection costs would feed directly into the import VAT calculations, pushing up the final figure.

The uncompromising attention to detail and the time these checks will add to operating costs — meaning that they should be blamed on a new incoming government in the wake of a general election. This morning’s BBC news carried an item to the effect that MPs standing down at the next election, or defeated at the ballot box should continue to be paid for four weeks instead of the current fortnight. Someone in Westminster is reading the writing on the wall.