The further food travels, the more it should cost. Logically, yes, but the full story may not be quite so simple. With ingredients travelling literally half way round the world, it is no simple matter to differentiate one proposition from another. Take the example of 1925 loaf of bread, in the previous post. The starting point is 20-stone sack of flour that anyone could visualise for themselves, suppposedly costing 42 shillings and a halfpenny. There was, in those days, total silence from the millers concerning where their wheat came from, let alone what it might have cost. Since millers earn a living from making flour, their reticence is understandable.

By creating a synthetic starting point for the journey that would put a loaf of bread on the table, millers were able to influence the British public’s notion of what bread ought to cost. The 42 shilling sack was not a hard sell, it was a working price point for those years. However, the Linlithgow committee, to a man, refused to make any comment on the prices of wheat, wherever it might have come from. In one sense, wheat and bread pass through very different markets, yet the two are joined at the hip for some purposes, notably if supplies fail: no wheat, no flour, no bread. It is that simple.

All through the latter years of the nineteenth century, British ports were unloading grain from every corner of the known world. For most people, grain imports were a permanent fixture and, as part of the British Empire, this happy state of affairs would somehow be left continue. However, the U-boat attacks, which started in 1916, jolted Britain into protecting inbound shipments of any description. From being adventuresome and exciting, life on a long haul merchantman took on a more challenging aspect as the U-boats extended their range from the concrete bunkers at Rochefort, comfortably crossing the Bay of Biscay.

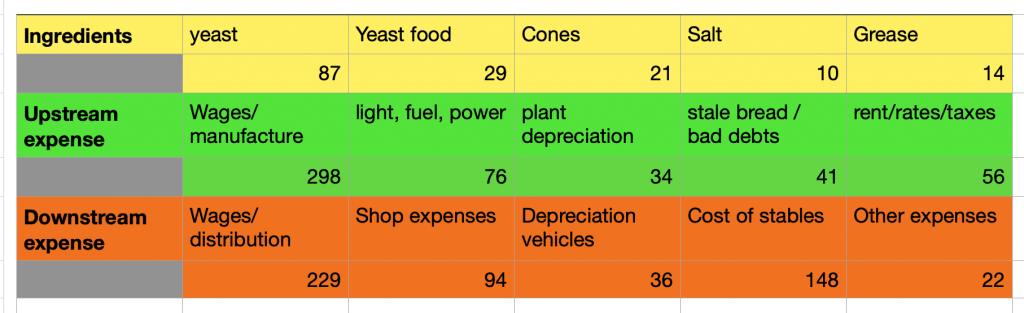

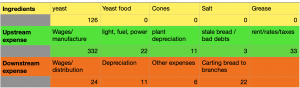

The Linlithgow committee provided four business snapshots based on live data (1923 figures..) to illustrate how the sector operated. There is no way of telling how much m, but the ones they published cast some light on the baking sector. Only theWar Office refused to share any data. The most detailed is based on figures from the National Association of Master Bakers’ and a number of local associations. The Industrial Co-operative group gave a terse rendering of the Co-op’s pricing structure, which differs in smalll but significant ways from retail rivals. Third is a glimpse of the War Office bakery, in Aldershot. It went to extraordinary lengths to say nothing. For the time being, I cannot locate where Butler Brothers traded, but the firm operated a number of branches from a central bakery.

The Linlithgow committee provided four business snapshots based on live data (1923 figures..) to illustrate how the sector operated. There is no way of telling how much m, but the ones they published cast some light on the baking sector. Only theWar Office refused to share any data. The most detailed is based on figures from the National Association of Master Bakers’ and a number of local associations. The Industrial Co-operative group gave a terse rendering of the Co-op’s pricing structure, which differs in smalll but significant ways from retail rivals. Third is a glimpse of the War Office bakery, in Aldershot. It went to extraordinary lengths to say nothing. For the time being, I cannot locate where Butler Brothers traded, but the firm operated a number of branches from a central bakery.

This could not come too soon, as inter-war businesses set about restoring their delivery systems. When trying to track the development of value in the pricing of bread and bakery goods, the editor of Industrial Peace, Major W Melville, conceded that the public grasp of the price structure was “little understood”. The only accessible estimates came from the Linlithgow Report and started outside bakeries with the purchase of sacks of flour. From the plains of north America, the vast expanses of Australia, to the more modest arable holdings of England, Linlithgow collects the entire growing stage of breadmaking flour into a single undifferentiated lump.

This could not come too soon, as inter-war businesses set about restoring their delivery systems. When trying to track the development of value in the pricing of bread and bakery goods, the editor of Industrial Peace, Major W Melville, conceded that the public grasp of the price structure was “little understood”. The only accessible estimates came from the Linlithgow Report and started outside bakeries with the purchase of sacks of flour. From the plains of north America, the vast expanses of Australia, to the more modest arable holdings of England, Linlithgow collects the entire growing stage of breadmaking flour into a single undifferentiated lump. The disadvantages of average returns are there for all to see. Melville put it like this: “No evidence offered in respect of price structure of flour. My inquiry begins at the point at which the baker buys his flour from the miller.” The opening price of breadmaking flour in January 1923 was 42 shillings and a penny. There is no indication of whether this should be taken as an “asking” price or a “taking” price, as given in a trade paper, meaning that flat pricing goes out of the window, speeded on its way by discounts applied at strategic order volumes. The figures discussed in the Linlithgow report were fixed during a time when flour prices were starting to fall, leaving a number of question marks over the validity of 42 shillings and a penny as a credible price for a sack of flour at this time.

The disadvantages of average returns are there for all to see. Melville put it like this: “No evidence offered in respect of price structure of flour. My inquiry begins at the point at which the baker buys his flour from the miller.” The opening price of breadmaking flour in January 1923 was 42 shillings and a penny. There is no indication of whether this should be taken as an “asking” price or a “taking” price, as given in a trade paper, meaning that flat pricing goes out of the window, speeded on its way by discounts applied at strategic order volumes. The figures discussed in the Linlithgow report were fixed during a time when flour prices were starting to fall, leaving a number of question marks over the validity of 42 shillings and a penny as a credible price for a sack of flour at this time.