In the wake of changes brought about by the revolution, the focus of the French economy shifted. The 18th century was a time when international trade was operating in what people used to call triangular trading patterns. Starting in the UK or a European port, ships would sail to ports on the African coast, where they collected shipments of slaves before leaving for the Caribbean. Many died aboard ship, others within days or weeks of arriving. The ships stayed tied up while they were loaded with tea and sugar before returning to London, where these luxury products were taxed and sold on.

Carrying food safety is a bit like a fairground ride: it appears chaotic at first sight, but the staff who have to work on the rides develop very finely tuned responses to changes in their work.

There is a more than a touch of narrative enthusiasm surrounding the lives and work of such industry demigods as Nicolas Appert; Louis Pasteur; Antoine-Augustin Parmentier. Many of the robust and worthy food industry leaders of the 19th century were also buried in the Parthenon, provided the body was not in an advanced state of decay. Legendary French family food businesses, just like their founders, have been long-lived, profitable and for those tourists who thought that Paris was as good as it gets, a source of wonder to passing visitors to France. There are many competent food companies working in obscure corners of la France profonde and a lot of them knock the parisians into a cocked hat.

Take a scrap of paper and start writing down a list of French firms. As you start looking for famous businesses and household names in towns and cities across France, you will find highly reputable companies with postcodes that spell out traditional landscapes rather than modernity. For me, the four generations of the Hénaff family come to mind: starting with very simple ingredients, they have a very small staff, but manage a huge production schedule. due to the efforts of third generation family member Jean-Jacques Hénaff. His core product is the canned Paté Hénaff, perfected at the Hénaff family’s manufacturing site in Pouldreuzic on the Breton peninsula. Should you like fungi, look up the Borde mushroom packing plant. All three generations were busy sorting and cleaning fungi, when I visited.

The tropical peasants who supply large quantities of almost dry fungi used to top up the sacks with ferrous waste to bulk up the weight loss in the drying stage. Nobody ever mentions the overweight sacks to the suppliers, for one very simple reason. So long as they carry on using scrap iron pellets, the metal shows up on a standard food industry conveyor belt. If the pickers change the material used to top up the sack weight, there is a risk that the substitution might not be detected in time, with potentially expensive litigation.

Elsewhere, in the south of France, spirit manufacturer, Matthieu Tesseire was politically active during the early 18th century. By 1720 the Tesseires had spotted the risk of a change of government, sold their land and sailed to the Caribbean, where nobody was challenged for their politics. The family devised a reliable and safe way of transporting sugar to metropolitan France, earning a fortune as they went. As the generations passed, they became increasingly argumentative and ongoing feuds within the clan finally pushed André Tesseire to restructure the business as a twenty first century corporate entity, in a despairing bid to prevent personal emnities from tearing up a multi-million cash cow into commercial confetti.

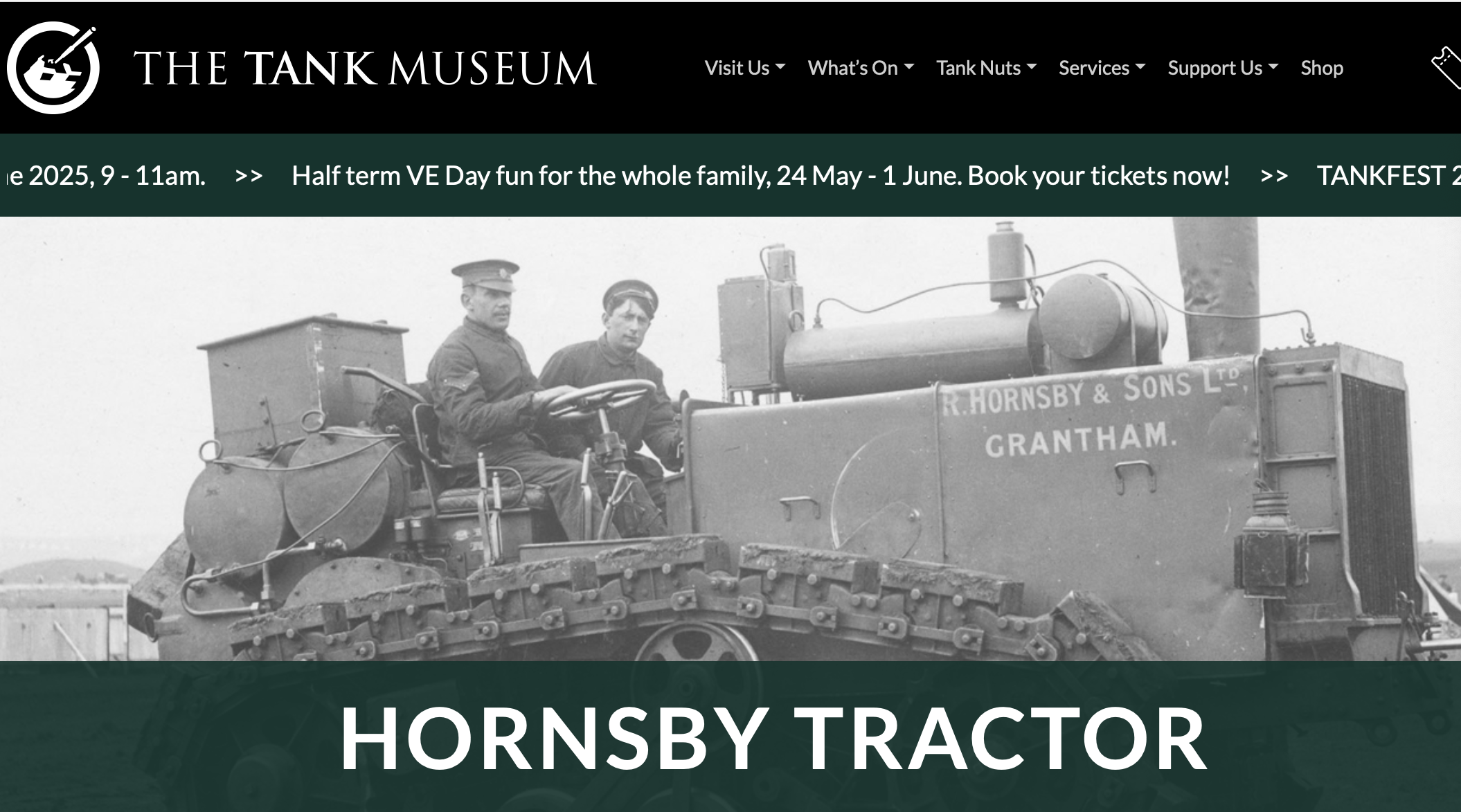

In the years leading into the 19th century, transport set operational ceilings for distribution systems, but once the age of steam was in motion, bigger load sizes and greater carrying capacities resolved a lot of the once-intractable issues.

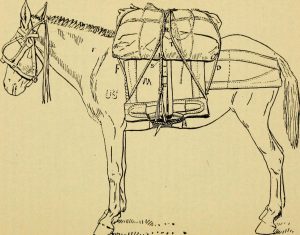

Town-dwelling horses were kept in grouped stables, or mews, usually bearing the name of the street they served. The equine diets were the standard fare of working horses of the day: hay, oats and roughage, washed down with water at intervals. Horses were the prerogative of the very rich or tradesmen who could cover their outgoings from their business. Agricultural businesses occupied the middle ground in this polarised rule of thumb scenario. The more successful ones worked with established lines of Percherons, Cobs or Shires, often breeding their own draft animals and systematically avoiding the saddle horse fraternity.

Town-dwelling horses were kept in grouped stables, or mews, usually bearing the name of the street they served. The equine diets were the standard fare of working horses of the day: hay, oats and roughage, washed down with water at intervals. Horses were the prerogative of the very rich or tradesmen who could cover their outgoings from their business. Agricultural businesses occupied the middle ground in this polarised rule of thumb scenario. The more successful ones worked with established lines of Percherons, Cobs or Shires, often breeding their own draft animals and systematically avoiding the saddle horse fraternity.

Twenty five years ago Europe was in a state of flux. Many differing political agendas were being promoted in the belief that drafting the right regulations would somehow automatically unlock all the expectations with little or no further discussion or purpose.

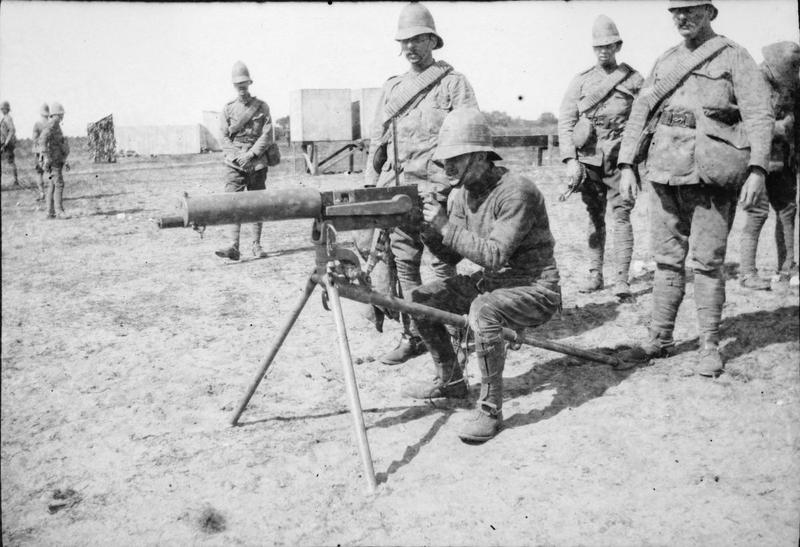

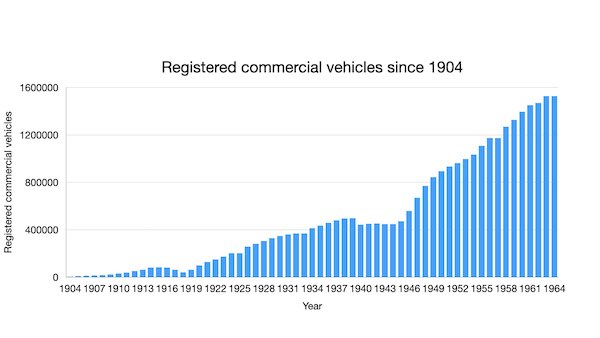

Twenty five years ago Europe was in a state of flux. Many differing political agendas were being promoted in the belief that drafting the right regulations would somehow automatically unlock all the expectations with little or no further discussion or purpose. Urban Food Chains has chipped away at a series of posts on the introduction of heavy machine guns which carried out a mechanised cull of thousands of working horses and pack animals. Intentionally or otherwise, the result was to clear the way for commercial motors of different sorts on British roads. Rule of thumb loading practices for draft animal at the time would have been about 20% bodyweight. Given that the working life of a horse can be up to 20 years and you have to spend four years feeding and training them before putting them to work, there was no point in sending fit young horses to battlefields to die within weeks of arrival having realised only 0.00520833 recurring of their potential work capacity (one month, a notional average) had they lived to work for 16 years, or close on 200 months.

Urban Food Chains has chipped away at a series of posts on the introduction of heavy machine guns which carried out a mechanised cull of thousands of working horses and pack animals. Intentionally or otherwise, the result was to clear the way for commercial motors of different sorts on British roads. Rule of thumb loading practices for draft animal at the time would have been about 20% bodyweight. Given that the working life of a horse can be up to 20 years and you have to spend four years feeding and training them before putting them to work, there was no point in sending fit young horses to battlefields to die within weeks of arrival having realised only 0.00520833 recurring of their potential work capacity (one month, a notional average) had they lived to work for 16 years, or close on 200 months.