Yes, this week is FairTrade week, when a growing number of ethically-traded products take centre stage in retail premises up and down the country. To be sure, the FairTrade movement works hard and has achieved a lot for growers all over the world.

Many of the core FairTrade range of products were first grown on plantations, the building blocks of forced labour. British-owned tea plantations in the 19th century responded to the abolition of slavery by ejecting former slaves and bringing in cheap, indentured labour from China and elsewhere in Asia. Slavery by another name, it can be argued.

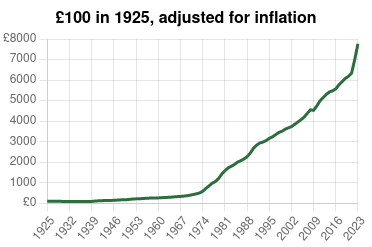

The much-argued over compensation that was paid out in the years following slavery’s abolition went to the slave-owners, to compensate for their lost profits. At that time, nobody thought to compensate the former slaves or their families for the upheaval and loss caused by the wholesale removal of men and women with working lives ahead of them, who were taken halfway round the world to work on sugar plantations or the like.

The building of today’s FairTrade movement marks a welcome change in how the world views food producers. It would be easy to overlook the origins of so many products before the the widespread recognition of ethical trading as a commercial policy in its own right.

There are more than 10,000 small-scale banana growers around the world, for whom FairTrade premiums earned GBP 31.8 million in 2020. The large-scale plantations of Latin America and elsewhere can still make economies of scale that get them preferential terms for everything from growing costs to shipping and distribution. But their existence is not a direct threat to FairTrade growers on the scale they once were, during a time when the average asking price for bananas in UK supermarkets dropped from 18p to 11p apiece.

There are 1.9 million FairTrade food producers around the world, earning a living growing tea, coffee, cocoa and a wide range of other agricultural products. In 2020, 1,880 producer organisations earned GBP 169 million in FairTrade premiums. The visibility of FairTrade products make it a successful brand with a strong appeal to consumers.