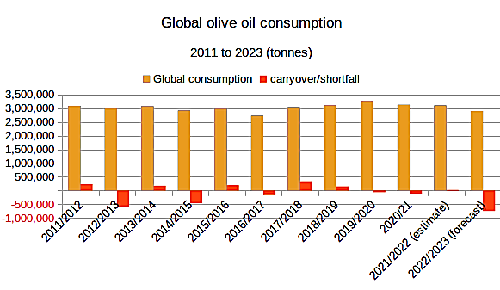

International olive oil packers face a very real threat of gaps in stocks of olive oil before this year’s harvest comes onstream. There is reason to believe that without any carry-in stocks, the scenario will be repeated next year. Prices have been high for months, as dwindling tonnages have been shipped from emptying tanks. Costs are not expected to ease before May 2024. This is an unprecedented situation, even to the industry veterans who remember the 1990s.

The Turkish government has banned bulk shipments of olive oil until November 1, as Italian and Spanish packers scoured the markets for available tonnages. The 2021-22 crop year came close to 230,000 tonnes of olive oil in Turkey, while official sources are predicting a record 400,000 tonne crop for the current crop year. The country has a large table olive sector, which is also expecting a bumper crop of 700,000 tonnes. The way the two harvests are managed reflect the different product requirements, but variables such as oil content and moisture content have a degree of wriggle room. Table olives are fragile and demand very careful handling to remain visually perfect, while olives bound for the pressing mill need to be intact but not necessarily pristine.

Turkey also produces three quarters of the world’s hazelnuts, with average crops of around half a million tonnes inshell equivalent in recent years. There are lingering memories among olive oil traders of instances when consignments were topped up with hazelnut oil, which is very hard to detect when mixed with olive oil in small quantities. Such adulteration introduces a nut allergy risk, proportional to the percentage added. It requires specialist laboratories using either chromatography or spectroscopy to detect it. The confident predictions of record olive oil tonnages in Turkey’s current crop year may not be completely fortuitous.

In June, Portugal’s producers were predicting a trend-busting crop topping 100,000 tonnes, maybe even a record 126,000 tonnes. Whether it turns out to be a record harvest or not, it will all sell through in very short order. There is reason to suppose that the country is benefiting from its extensive Atlantic facade, even though Portugal is not a major producer.

Normally a net importer of olive oil, the southern hemisphere olive oil producer Ecuador is preparing to empty both its harvest and its reserves into a transient seller’s market. In terms of tonnages, this is unlikely to top 3,000 tonnes The southern hemisphere crop is in its final stages this month and every tonne harvested has a number of potential buyers in Europe.

The growing concerns over olive oil supplies are surfacing in many different ways across southern Europe. Croatian olive oil producers are critical of the restaurant trade’s insistence on putting cheaper imported olive oils on tables, while local specialities are promoted on the menu. Award-winning olive grower Ivica Vlatkovic put the cat among the pigeons by urging restaurateurs should sell 100 millilitre bottles of good quality olive oil as part of the cost of a cover.